As rooftop solar emerges as Australia’s fastest-growing source of power, a new report is urging governments to take the $25 billion of consumer installed energy resources seriously – in particular, the role they can play in rapid decarbonisation.

The IEEFA report turns the policy spotlight on residential distributed energy resources (DER) ranging from rooftop solar and battery storage to demand-responsive appliances, like hot water services and pool pumps.

In Growing the sharing energy economy, DER expert Gabrielle Kuiper details six policy changes she says could unlock the potential powerhouse of these behind-the-meter energy assets in a way that further benefits consumers, while also boosting Australia’s chances of hitting its climate and renewable energy targets.

DER are currently worth some $25 billion, with an expected $250 billion more anticipated to be installed over the next two decades if five million households invest an average of $50,000 each in solar, electric vehicles and smart electric appliances.

“Prioritising support for DER has the potential to smooth out some of the bumps in the energy transition road,” Kuiper said in a statement.

“We’ve seen in recent weeks the whole of South Australia was powered by household solar for a few minutes. This is a phenomenal milestone, and we can do even more to make the most of our abundant sunshine.”

The true champion today of the energy transition is rooftop solar but the future is in smart electrified hot water systems, smart demand-responsive appliances, and behind-the-meter (BTM) storage.

“These areas of policy and regulation have not had the attention they deserve. What the IEEFA report does is set out how more solar, more batteries and more flexible demand in the grid can put downward pressure on wholesale and network costs, but it needs action by energy ministers in six areas to unlock those benefits,” Kuiper says.

“At present DER are already benefiting the people who purchased them and the broader grid, but those benefits could be so much greater if we get the technical, regulatory and market integration right.”

The six changes the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis (IEEFA) report is calling for are:

1. Ensure appropriate technical standards are in place so DER performs consistently and compliantly with networks, has the necessary features to support consumer needs, and enables DER to participate in markets.

2. Remove static constraints on existing solar by rolling out flexible exports, as South Australia has done, and improve voltage management. Conservative estimates by the Victorian government suggest improved voltage management will lower costs for consumers by $30 million per year.

3. Unlock flexible demand by opening up the wholesale demand response mechanism (WDR mechanism) to households as well.

4. Fast-track distributed storage through prioritising and providing financial support for distributed battery systems and allowing aggregated BTM storage to participate in the Capacity Investment Scheme.

5. Create a level-playing field in network services by reviewing how networks make money and changing that from providing one-way electricity distribution to enabling two-ways flows.

6. Ensure fit-for-purpose governance so it supports rapid decarbonisation.

Growing demands for DER engagement

The six recommendations mirror the five options outlined by Nexa Advisory also this week, which said that the current playing field has created an us-versus-them approach: DER owners don’t trust the intentions of large energy companies and network operators, and the latter are frustrated by the impact of ungoverned DER.

Kuiper instead called for a “sharing economy” of DER.

Owners of these resources can trade their services in return for payments for services such as supplying extra electricity, reducing demand on the grid, or Frequency Control and Ancillary Services (FCAS) for grid security.

Crucially, any sharing economy must be voluntary with no central controller.

“Ideally, households and businesses can choose to sign up with their retailer, battery manufacturer, car manufacturer or other third-party aggregator. The consumer owners will have a choice just like they do about opting into Airbnb,” the report says.

“Each company that offers payments for consumers to be part of the sharing energy

economy will have its own VPP. As Origin’s leadership noted last year, a VPP is a “capital- and cost efficient tool to create capacity.”

Wasted years

Earlier this month Kuiper wrote a frustrated editorial for RenewEconomy outlining how Australia has wasted years by having equipment such as air conditioners and hot water systems built to allow them to interact with the grid and be a shared resource – but preventing them from doing so through a lack of regulation.

“The National Electricity Rules (NER) weren’t written with Distributed Energy Resources (DER), such as air conditioners or solar panels in mind, but as DER become a more and more important part of the energy system, we need to make sure they are designed to smart standards and are included in the NER,” she said.

“Without these standards in place, DER can’t participate in energy markets on an equal footing with large wind and solar farms.”

The Energy Security Board, the Australian Energy Market Commission, the Australian Energy Market Operator (AEMO) and the Australian Energy Regulator have been trying and failing to create rules to bring DER into the fold since 2019.

DER best way to reach 82%

The struggle to reach the federal target of 82 per cent renewables in the grid by 2030 is real: in 2022 the grid was 37.7 per cent renewable, but new large-scale wind and solar reaching financial close have stalled in the face of supply chain risk and dense bureaucracies.

Just 400 megawatts (MW) of new renewables investment was financed in the first six months of 2023 when the country needs 5 gigawatts (GW) by 2030, according to Clean Energy Council statistics.

Yet for the last three years almost 3GW of rooftop solar has been added annually to total more than 22GW in the National Electricity Market (NEM) today.

The benefits of rooftop solar as a player in the NEM have already been quantified.

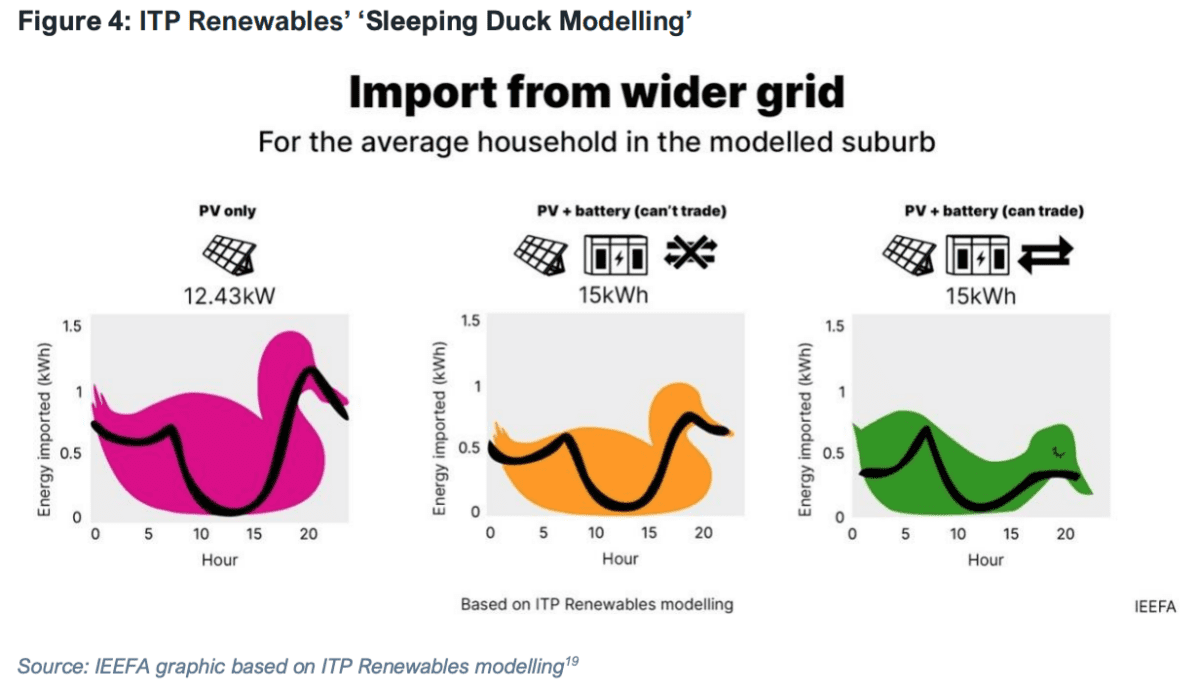

A report by ITP Renewables this year, based on 70 per cent of households having rooftop solar, found the dreaded midday ‘duck curve’ is vastly mitigated by having behind-the-meter devices able to actively trade in the market.

The technology reduced average annual prices across the NEM by by $3.1/MWh in 2017, $4.7/MWh in 2018 and $6.4/MWh in 2019 from what they otherwise would have been, according to an analysis by Bruce Mountain and colleagues at the Victoria Energy Policy Centre.

Behind-the-meter resources also co-locate generation and load, reducing the reliance on transmission and distribution networks – and reducing, if managed well, extra spending on building out those poles and wires and thereby putting pressure on energy bills.

Modelling shows that home batteries that are optimised to participate in energy markets can deliver just the kind of grid stability services market participants are currently searching for, says Evergen principal VPP solutions engineer, Stephen Pritchard.

“With the right market and network signals, optimised residential batteries will be capable of doing some heavy lifting for stabilising the grid, and if done right, battery owners can be active participants in the market and benefit from offering this service, so that everybody wins!” he wrote.

DER such as rooftop solar and batteries also make households more resilient, which can be the difference during emergencies such as bushfires which can cut communities’ off from power networks.