Fossil fuel companies have continued to pour millions of dollars in gifts onto the major political parties, with the Labor Party alone collecting more than $863,000 in donations from oil, gas and coal producers in the first full year of the Albanese Government.

The Australian Electoral Commission released the latest batch of political donation disclosures on Thursday morning, detailing the donations received by political parties between 1 July 2022 and 30 June 2023.

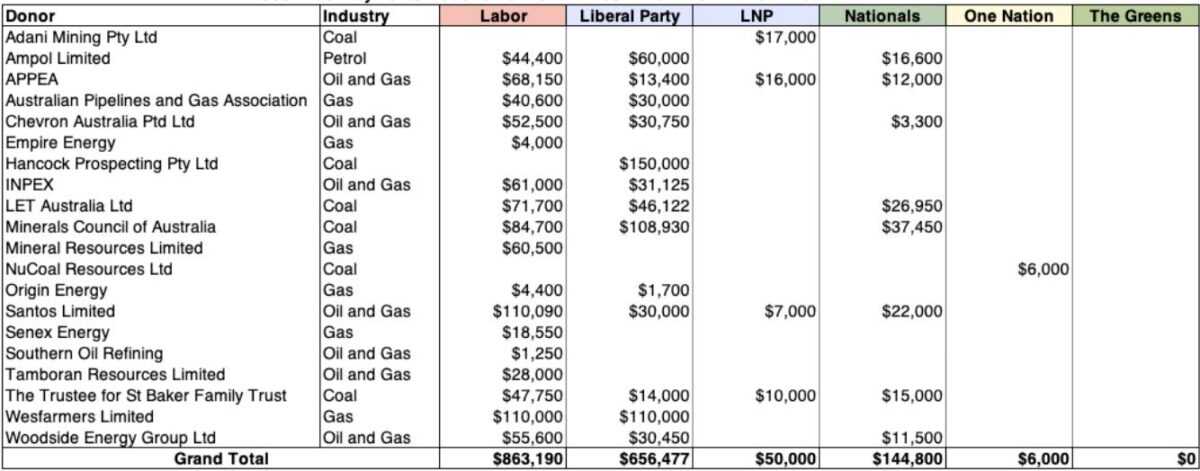

The data reveals fossil fuel companies continuing to make sizeable donations across the political spectrum – a total of $1.78 million – shared by the Labor Party, the Liberals and the Nationals, and from the likes of Adani, Woodside, Santos and Chevron.

In the first full year of the Albanese Government, fossil fuel companies poured $863,190 into Labor Party accounts, with the biggest donations provided by gas producers Santos ($110,090) and Wesfarmers ($110,000), lobby group the Minerals Council of Australia ($84,700) and clean coal advocates LET Australia ($70,197).

Significantly, oil and gas giant Woodside gifted $55,600 to Labor Party entities, alongside Chevron, who added $52,500. Fossil fuel industry lobby group APPEA – which has railed against Labor’s gas market interventions – added a further $68,150.

These donations were all made during a period when the Albanese Government was making crucial decisions about the expansion of Australia’s oil and gas industries – and moving to introduce price caps on gas supplies in an effort to lower prices for consumers.

It is a perverse feature of Australia’s political system that while the Ministerial Code of Conduct expressly prohibits ministers from receiving gifts ‘in connection with performing’ their official duties as a Minister, fossil fuel interests can pour funds into the coffers of the political party they represent.

To that end, it is unsurprising that the Coalition continued to benefit from its friends in the oil, gas and coal sectors.

The Liberal Party received $656,477 during the year from its fossil fuel backers – with the largest donation of $150,000 coming from Gina Rinehart’s Hancock Prospecting. The Nationals’ donations almost reached $200,000.

The National’s largest fossil fuel donation – of $55,000 – was sneakily made by Adani Mining, which was directed via the holding company (Laneway Assets) for the party’s ‘National Policy Forum’.

The merged Liberal-National Party in Queensland received an additional $50,000, with Adani Mining also contributing its biggest fossil fuel donation of $17,000.

Other beneficiaries of fossil fuel money included One Nation, which received $6,000 from NuCoal Resources.

The Greens did not report any funds from fossil fuel companies, with all the party’s reported donations coming from individuals.

Donations to the campaigns of independent candidates, including the successful ‘Teal’ independents, were disclosed in November last year, with the Climate 200 group being the most significant financial backer.

Today’s data shows energy trader Marcus Catsaras making a $1 million donation to the Climate 200 group.

For a non-election year, the amount of donations is significant. As I reported last year, fossil fuel companies tipped more than $1.3 million into the accounts of the major party ahead of the 2022 federal election.

This amount was exceeded in the 2022-23 year, with a further $1.78 million being donated by fossil fuel interests.

However, when discussing federal donation data, it is essential to note two critical issues with the latest release.

The first – the data released today covers donations for the year to 30 June 2023. At best, we’re learning about donations that are already seven months old. At worst, we’re learning about donations from as long as 19 months ago for the first time.

Secondly, we only receive information about the very largest donations. For the 2022-23 year, the donation disclosure threshold was set at $15,200.

Any donation of $15,200 is a considerable amount of money and well above the level of donation the average person can afford to make. All donations below this amount do not need to be disclosed publicly.

Barry O’Farrell resigned as NSW Premier over the receipt of a $3,000 bottle of Grange Hermitage wine – but a fossil fuel company could donate $15,000 to the party of government, and we might not even know about it.

The donation disclosure thresholds are also indexed in line with inflation, which is partly why they have leapt to particularly high levels over the last couple of years.

For next year’s disclosures, the threshold will be set at $16,300 – again, a huge amount that enables very influential donations (and their donors) to remain hidden from view.

As the Centre for Public Integrity has long argued, Australia’s democracy is not well served by such high disclosure thresholds. As much as a quarter of funding received by political parties is not publicly known. This has amounted to more than $1.5 billion over the last 25 years or so – a vast amount of ‘dark money’ that has the potential to influence the operation of government.

The lowering of the donation thresholds would be an excellent start. Donations disclosure thresholds for State and Territory political parties in NSW, Queensland and the ACT, for example, are set at $1,000 and not indexed annually.

Donations could also be published in real-time, or near real-time.

As the director of the Australia Institute’s Democracy and Accountability Program, Bill Browne said, voters deserve to know who’s potentially using money to influence government decision-making.

“We are learning today whether businesses made political donations 18 months ago. These lags and other loopholes make it difficult to see how politicians and political parties are being funded – and by whom,” Browne said in a statement on Thursday.

In 2015, the High Court upheld a ban on political donations from property developers to NSW state political parties – citing the ‘dependence of property developers on decisions of government’ for project approvals’ and the resulting potential for corruption and undue influence on the State government.

The High Court held that while banning donations from property developers was a burden on the ‘implied freedom of political communication’ that is provided by the Australian Constitution, the ban was, on balance, better for Australian democracy.

It is clear that fossil fuel companies are just as dependent on federal ministers for approvals of their multi-billion-dollar coal and gas projects – projects that are contributing to a worsening climate crisis – and they shouldn’t be allowed to exert this level of ongoing financial influence over political parties.