Carbon dioxide emissions in 2022 will pass pre-pandemic levels, setting the world on course for a 50 per cent chance of breaching 1.5°C of warming by 2031.

Total carbon dioxide emissions for this year are projected to touch 40.6 billion tonnes, according to the 17th annual Global Carbon Budget released today, a worldwide research effort to measuring the global carbon cycle every year.

“Starting next year we have nine years left, if we stay with the same level of emissions to reach 1.5°C, with 50 per cent likelihood, 18 years for 1.7°C, and 30 years for 2°C,” said Dr Pep Canadell, director of the Global Carbon Project at CSIRO.

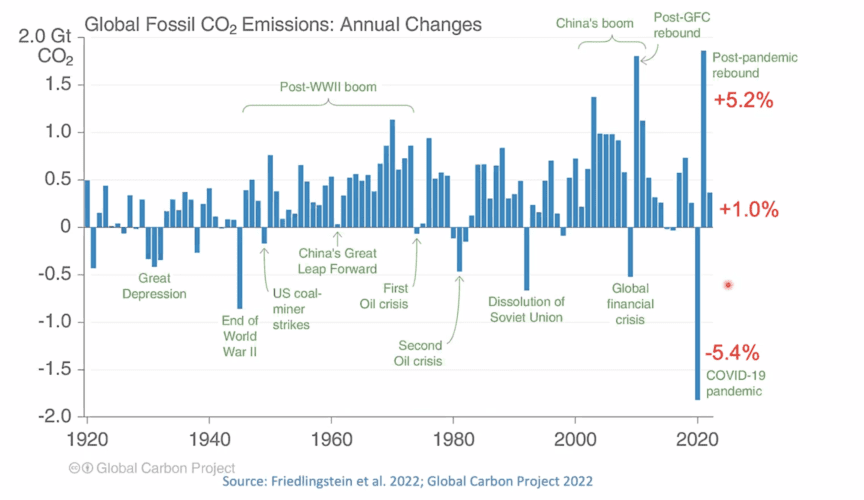

“To reach net zero CO2 emissions… from where the data say where we are now… if we want to do that by 2050 we would have to decline our global emissions by 1.4 gigatonnes of CO2 every single year, which is a very similar amount to the fall in greenhouse gas emissions we saw in 2020 due to the COVID-19 lockdowns.”

That outlook is slightly more positive than that put forward by the World Meteorological Organisation last year, which gave the world a 50:50 chance of 1.5°C warming by 2026.

Some 90 per cent of the 2022 total comes from fossil fuel burning, partly driven by the rebound in air travel after COVID19 restrictions lifted and led by the US and India. Fossil fuel emissions in China and Europe have dropped.

The remainder is from land-use change and primarily from Indonesia, Brazil and Democratic Republic of the Congo.

Land-use change emissions have actually been trending downwards for the last decade but not because deforestation and organic land burning has slowed, but because of regeneration efforts. Canadell says deforestation of pristine forests continues apace.

2022 also sets another record with the volume of carbon dioxide accumulation in the atmosphere projected to hit 417.2 ppm in 2022. Land and ocean sinks continue to take up around half of carbon dioxide emissions, but are becoming less efficient as temperatures rise.

Rate of CO2 growth slows

There is some good news: the rate at which fossil fuel emissions are increasing has slowed dramatically, from 3 per cent a year in the 2000s to about 0.5 per cent in the last decade.

“We are at an all-time record of fossil fuel CO2 emissions,” said Canadell during a webinar to present the research.

“We see no immediate peak let alone decline that could happen any time soon in the next two to three years. Really, the peak is further ahead.”

Australia has a hard road to 2030

Australia’s story is slightly more positive in the sense that achieving the government’s legislative 43% emissions reduction target by 2030 is possible, albeit difficult.

It is also more advanced than the rest of the world, having already warmed by 1.4°C since records began in 1910.

The country is about half way to achieving the 43 per cent target but it’s taken 17 years to get there and we only have eight years left to cut the remainder, says Professor Frank Jotzo, director of the Centre of Climate and Energy Policy at ANU, who was not involved with the Global Carbon Project.

“A significantly stronger reduction than 43 per cent could be achieved in Australia. There’s plenty and plenty of unharvested low hanging fruit, after decades of inaction on climate policy, in terms of energy efficiency, in terms of fuel switching, in terms of decarbonisation of electricity to speed that up,” he said.

“But unless more is done in terms of policy intervention, we may not reach that target. It requires effort, but that effort is readily achievable.”

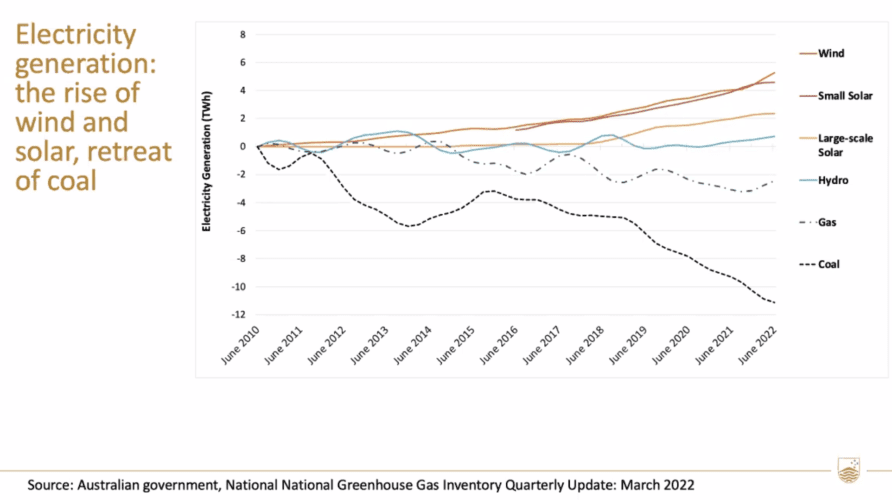

That effort involves a consistent and comprehensive set of policies that target the electricity sector in particular.

“The plan is to have a carbon price in the industry sector for the large industrial installations in the Safeguard Mechanism. There’ll be a baseline and credit scheme… financial incentives within each of these industries to reduce emissions at some unknown price level. The question becomes why haven’t we got the same carbon price incentive in the electricity sector? So that’ll be the next frontier,” Jotzo says.

He recommends incentivising large amounts of energy storage and creating a national rather than state-by-state process to shut down coal fired power plants. He also says agriculture will need to be brought into the tent as it is a large source of emissions that aren’t coming down.

Biggest emitters versus biggest losers

But while it looks like who is a climate baddie and who is a goodie have been shaken up, the nuance shows all major countries are failing to do their part to reduce emissions.

China creates a third of global emissions. It is now the largest polluter on the globe. But its ongoing COVID-19 lockdown has damaged economic growth and particularly the once-thriving construction industry, and therefore slashed emissions.

“A big question mark is over big infrastructure investment in China and to what extent that will resume. So much of that very steep emissions growth that we’ve seen in China over the last 20 years really is related to the build up of cities, high rise buildings, train lines, motorways,” Canadell said.

“We may well expect the moderation of the emissions profile as well for China on account of of that as well as on account of the fact that more and more low zero emissions, energy sources are coming into the mix. Renewables, more nuclear as well, even more plans for hydroelectricity in China.”

The US now produces 14 per cent of the world’s total emissions. Its thriving shale gas industry is driving a rise of 4.7 per cent in those emissions and the mad, post-pandemic dash to get on a plane is pushing oil emissions higher too.

The EU is struggling under the weight of the Ukraine war-created energy crisis. Gas emissions in 2022 will drop by 8 per cent because Russia, which had supplied some 40 per cent of the region’s gas, cut off supplies. The counter balance is that coal emissions are up by 6.7 per cent.

In India, which now accounts for 8 per cent of global emissions, coal and oil are pushing emissions up by 6 per cent this year after the country continues to buy heavily discounted oil from Russia.