The Energy Collective Group

This group brings together the best thinkers on energy and climate. Join us for smart, insightful posts and conversations about where the energy industry is and where it is going.

Post

Climate Justice: Tallying Up the Rich World’s Carbon Debt

Climate change is arguably the most complex challenge the world has ever faced. The primary complicating factor is that those who cause the most climate damage (previous and current rich-world generations) and those who feel the worst effects (current and future developing-world generations) are two completely different groups. To complicate matters further, the monetary value of this injustice is highly uncertain.

In this article, I will attempt to quantify the value of the carbon debt those of us living comfortable lives in the rich world owe the developing world. But first, let’s lay out the reasoning for accepting such a debt in the first place.

The Moral Case for Rich-World Carbon Debt

Most likely, you’re reading this from a comfortable life in a developed society. Take a look around you. Everything you see that facilitates this state of material comfort has been built on the back of millions upon millions of tons of historical CO2 emissions. Let’s explore why that matters.

Climate change is about cumulative emissions

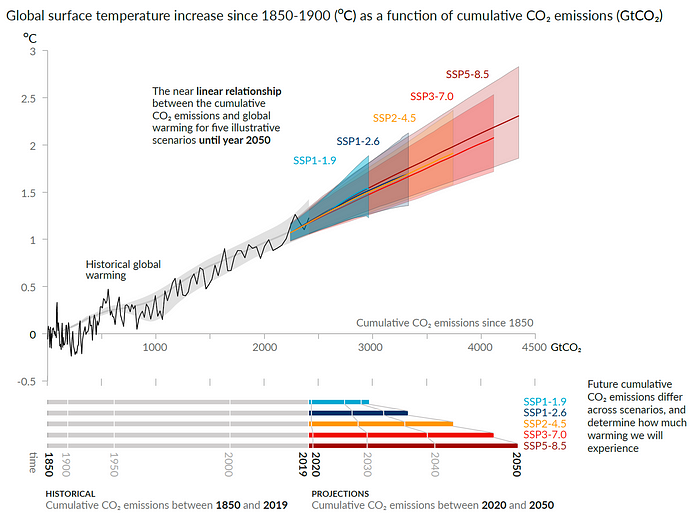

It is well established that the global temperature rises almost linearly with cumulative emissions.

The linear relationship between global temperature rises and cumulative emissions | IPCC AR6 WGI

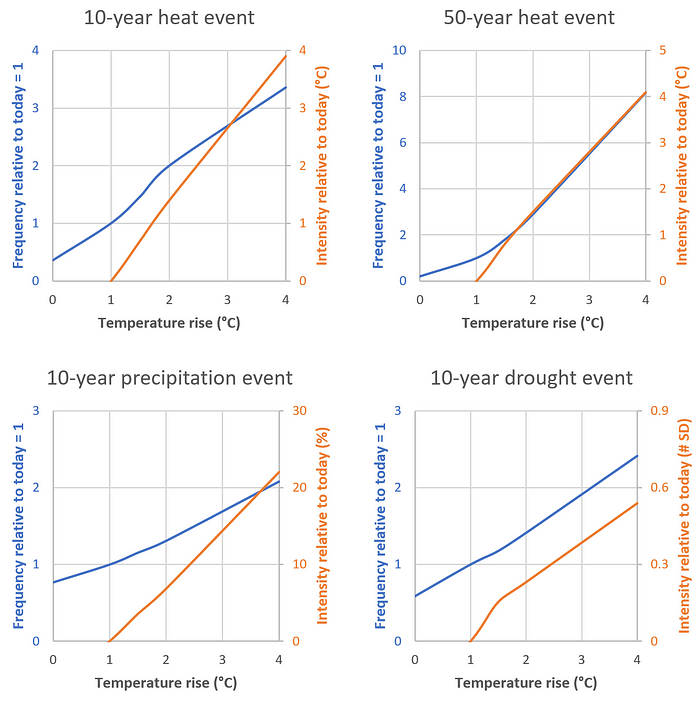

Similarly, the severity of climate impacts increases linearly with temperature.

A representation of the data from the IPCC report with rising temperature levels. The 10 and 50-year event baseline is a system with no climate change. # SD = number of standard deviations increase from the norm.

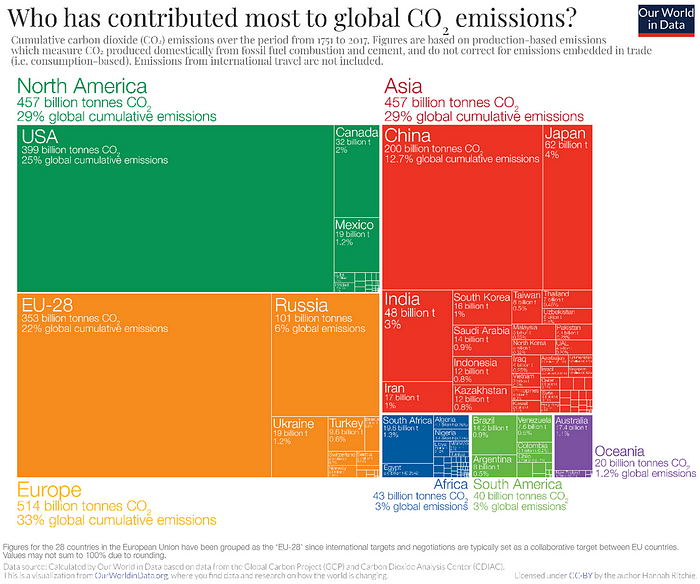

The rich world, here approximated as the USA, the EU, Japan, Canada, and Australia, stands for well over half of our historical emissions, even though these countries are home to only 12% of the world population.

A breakdown of historical emissions | Our World in Data

Thus, it is clear that a minority of privileged world citizens is responsible for the majority of climate damages to date (and into the medium-term future).

Mismatch in benefits from historical emissions

Rich-world citizens have benefitted tremendously from their trillion tons of historical emissions. Most of us take our fossil-fuel-derived privileges totally for granted, but it only takes a little bit of critical thinking to realize how much all this cheap and abundant fossil energy has enhanced our lives.

A hilarious video of the guy with the biggest legs you’re ever likely to see trying to produce the power needed to toast a piece of bread

Our historical CO2 helped us build a tremendous array of life-enhancing infrastructure, technology, and human capital that grant us a level of material comfort reserved exclusively for royalty served by hundreds of slaves in centuries past.

An illuminating Dutch illustration of all the “energy slaves” working in our homes

Here is a non-exhaustive list of the privileges our historical emissions have given us:

- Clean water at the turn of a tap

- Safe and bright light at the flick of a switch

- Indoor plumbing to instantly remove our waste

- A varied diet of foods from across the globe

- Plentiful energy to cook our food without harmful air pollution

- Multiple labor-saving devices taking care of our household chores

- Comfortable, spacious, and temperature-controlled dwellings

- Machines that can affordably transport us across the world in a day

- Advanced medical services that double our life expectancy

- Sophisticated education systems that teach us any trade we desire

- Free access to almost the totality of human knowledge

- A dizzying array of entertainment options, much of it at our fingertips

There are still hundreds of millions of world citizens without access to any of these privileges and billions who can only access some. The reason for their lack of privilege is simple: They were not lucky enough to be born into societies built on the back of billions of tons of historical fossil fuel emissions.

Six out of every seven world citizens live on less than $1000 a month (the vertical line) and one out of every four on less than $100 a month (please take a moment to imagine what that must be like) | Gapminder

Mismatch in costs from historical emissions

The mismatch in benefits from historical emissions is great, but the distribution of costs is even more skewed, only in the opposite direction. There are two primary reasons for the mismatch in climate costs: economic inequality and geographic location. Let’s discuss each in turn.

The wealthy societies built on our historical emissions not only grant us incredible material comfort; they also serve to protect us from the negative effects of a changing climate. Here are a few examples:

- Sturdy homes with reliable access to water and climate control protect us against all kinds of extreme weather

- In the rare case of a truly extreme event, advanced weather warning systems and access to modern transportation allow us to evacuate in time and our well-developed economies help us quickly recover afterward

- Diversified trade networks protect us from the effects of local crop failures

- Advanced healthcare systems protect us against any new diseases brought by shifting climate zones and treat injuries from extreme events

- Our large discretionary income will allow us to spend liberally on climate adaptation measures like seawalls and urban greening when needed

Again, hundreds of millions of developing world citizens do not enjoy any of these climate protection privileges, while billions only have access to some.

Some sobering scenes of climate vulnerability among India’s poor. Be sure to turn on the subtitles.

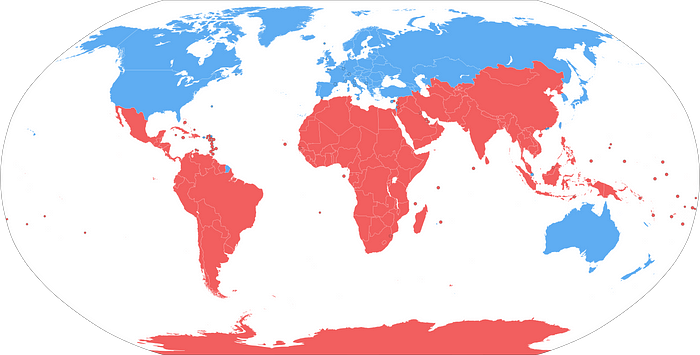

The general geographic location of the rich (Global North) and poor (Global South) further augments this complete mismatch in climate costs.

Map showing the Global North (blue) and Global South (red) | Wikipedia

In various aspects, rising temperatures actually make our lives more comfortable in the Global North. Yes, there are costs from more extreme weather events and heat waves, but a reduction in cold extremes brings clear benefits to those living in Northern latitudes.

Although rarely acknowledged, cold is actually a 10x bigger killer than heat. In fact, warming caused by greenhouse gas emissions saves about 160,000 lives per year relative to the year 2000. If we account for all the warming before the year 2000, this number may well triple to half a million.

Climate-related mortality costs by the end of the century are projected to be negative in the Global North and positive in the Global South (especially Africa) | Explore the data on the interactive Climate Impact Lab map

Aside from making life safer and more comfortable, rising temperatures in the Global North also save plenty of heating energy. Furthermore, it can boost agricultural production, supported by CO2 fertilization.

For the Global South, Africa in particular, these trends reverse mercilessly. With excess heat already being a problem, more of it will only make matters worse, causing more heat-related deaths, boosting energy demand for cooling, and harming agricultural yields.

In combination with a high degree of climate vulnerability resulting from poverty, these geographical factors mean that the vast majority of climate damages fall on the Global South, while the Global North could even enjoy a moderate net benefit.

Growth hampered by climate policy

Looking to the future, we find another layer of injustice. By far the best way in which the Global South can protect itself against a more hostile climate, while simultaneously improving livelihoods, is to rapidly develop its economy. Unfortunately, strict carbon budgets drawn up by climate experts and enthusiastically promoted by activists make it impossible for these nations to follow the proven Western model of economic development.

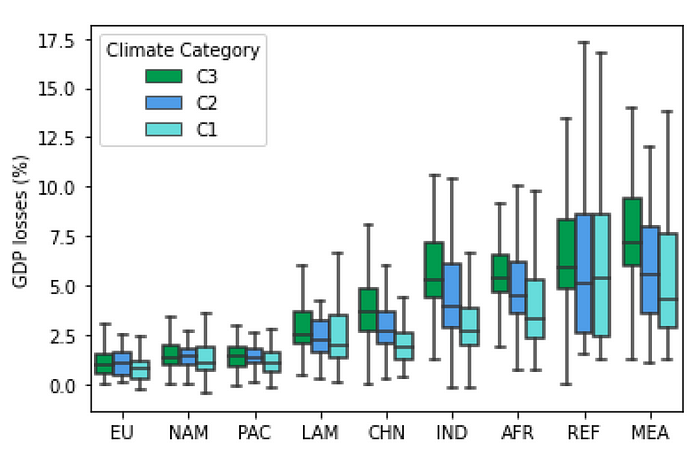

GDP losses in different world regions by 2050 resulting from idealized 1.5–2 °C pathways with immediate action and constant global carbon taxes. Western Europe and North America face low losses, China and India moderate losses, and Africa, East Europe, and the Middle East face high losses. | IPCC AR6 WGIII

As an example, the Chinese economic miracle needed three decades to raise the median per-capita income from $1.2/day to $13/day (an incredible achievement), emitting about 200 Gton of CO2 in the process. In other words, ultra-efficient China needed most of the world’s remaining 1.5 °C carbon budget to bring half its population (about 9% of world citizens) about one-third toward decent living standards. Clearly, if developing societies across the world improve their livelihoods with even 10% of this carbon intensity, we would smash our 2 °C budget in no time.

A common softening argument is that we now have cheap wind and solar power to replace all the coal-fired power plants that propelled China to where it stands today. While that is already a grossly oversimplified notion, I should also highlight that the production of steel and cement (the building blocks of modern civilization) emitted as much CO2 as coal power plants during China’s rise (see the notes in this previous article). While obstructing the construction of coal power plants is bad enough for developing world growth, obstructing industries like steel and cement would be far worse.

In summary, the rich world consumed a disproportionate share of the global carbon budget (and a broad range of other natural resources) to establish its high material prosperity (and climate resilience), precluding 6 billion developing world citizens from following suit. This realization just makes it all the more ironic when rich-world activists complain about rising developing world emissions from their comfortable fossil-built societies.

Ability to pay

Finally, we should acknowledge the fact that tax collectors have known for generations: The rich have greater discretionary spending, so they can afford to pay a higher share of their income.

Discretionary spending is the act of buying things we want but don’t really need (by “need” I mean the basics required for a decent life, not all the useless excesses our consumerist culture tells us we need). Thus, we can easily give this money to a better cause with little or no negative effect on our health or wellbeing. The vast majority of developing world citizens, on the other hand, need every bit of their income to afford the basics of life.

For this reason, a strong argument can be made that the rich world should take responsibility not only for the climate damages caused by their own half of historical emissions but for some of the other half as well.

After establishing the moral case for a rich-world carbon debt, the next task is quantification. Let’s start by finding the number of tons of CO2 equivalents for which the average rich-word taxpayer should take responsibility.

When should the debt accumulation start?

To be fair, the rich world should not be held accountable for greenhouse gases emitted before we knew that climate change posed a threat. Pinpointing when we had sufficient understanding to draw this line is tricky, but, after reading a short history of climate science, I will use 1965 in this assessment.

Could we have limited our greenhouse gas emissions after learning about the threat of climate change? Well, we might not have had affordable wind and solar power by that point, but we already had nuclear power, hydropower, bioenergy, energy efficiency, and the possibility of simply not falling so deeply into wasteful consumerism as we eventually did. Hence, it’s hard to come up with any reasonable excuse after we lost our ignorance.

Calculating per capita carbon debt

Combining CO2 emission data from the BP Statistical Review, the share of total greenhouse gas emissions originating from fossil CO2 (62%) from the IPCC WGIII report, the share of imported emissions from the Global Carbon Project, and publically available population data yields the following graph:

Cumulative emissions per citizen between 1965 and 2021 | Graph compiled from BP, IPCC, and GCP data

As illustrated, the average rich-world citizen owes their high level of material comfort to about 1000 tons of historical CO2 eq. emissions, with the US being the largest historical emitter per capita and the EU the lowest. In comparison, historical emissions from the rest of the world (including carbon-intensive China) are fully 6x smaller.

If the share of the population actively paying taxes is set to 45% (based on taxpayer information in the US), the average carbon debt per rich-world taxpayer amounts to 2294 tons.

Adjusting for the ability to pay

If the rich world were to take responsibility for half of the carbon debt of the developing world as well, the number given above swells to 3724 tons. This number is useful to keep in mind as an upper-bound estimate.

Estimating Monetary Debt

OK, now for the big question: How much money does the rich world owe the developing world to compensate for the unjust maldistribution of costs and benefits resulting from our historical emissions?

The direct cost of a ton of CO2

Climate change has a broad range of economic impacts, most of which are difficult to quantify. Many studies attempted such a quantification, and median estimates tend to end up around 50 $/ton, both in policy planning and academia.

However, the uncertainty range is very wide, ranging from negative numbers to values exceeding 2000 $/ton. Negative values arise from valuing effects like CO2 fertilization and reduced cold-related damages higher than costs from warming, whereas values at the high end assign a higher weight to edge cases of runaway warming and ecosystem collapse in the long-term future.

Indirect costs of tight carbon budget constraints

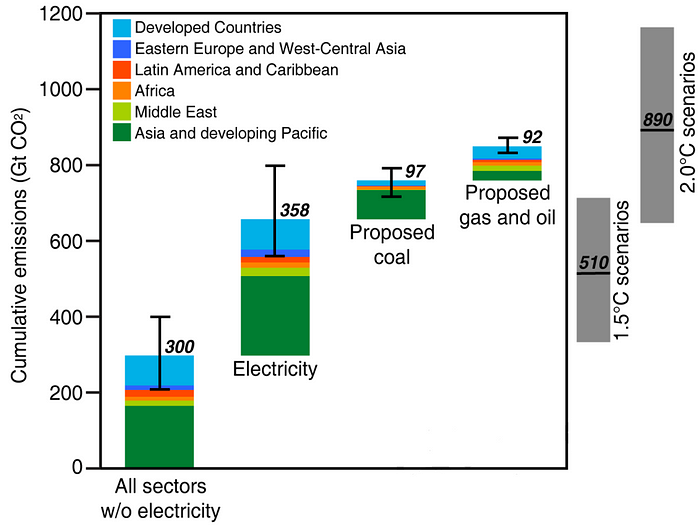

As already introduced in the section on the moral case for a carbon debt, a major effect of our historical emissions is that they have consumed most of the permissible carbon budget for keeping temperatures below 2 °C. Thus, the developing world is not permitted to use nearly as much fossil energy in building their societies as the rich world did. If the most stringent carbon budgets are considered, they will even need to tear down the energy capital they have constructed to date well before reaching end-of-life.

Cumulative emissions from existing infrastructure will already emit double the remaining 1.5 °C carbon budget (400 Gton by mid-2022) unless retired early | IPCC AR6 WGIII

The cost of this element to the developing world depends strongly on which global warming target we strive for. If it is 1.5 °C, we only have 10 years of current emissions left — an impossible task. If we permit 2.5 °C, however, the remaining budget becomes more than 5x larger, giving the developing world a fair chance at uplifting their citizens without being seriously inhibited by near-term limits on the use of fossil fuels.

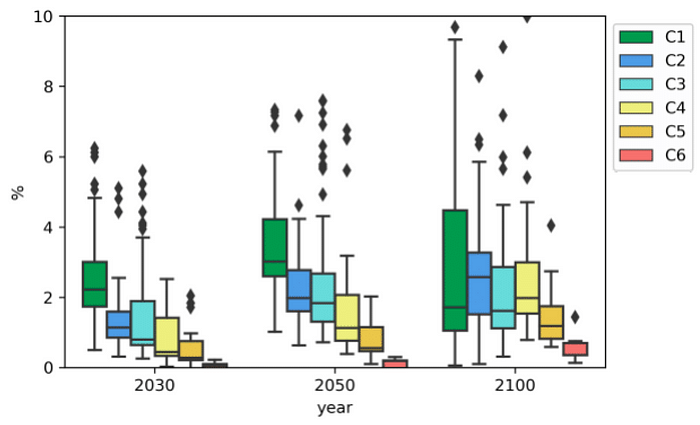

In the figure below, the 1.5 °C pathway leads to median losses of around 2.5% each year across the century, while the 2.5 °C losses are about 8x smaller. As illustrated earlier, developing world losses will be about double the average, implying 5% for 1.5 °C and 0.6% for 2.5 °C.

World GDP losses by various future years in idealized mitigation pathways with immediate action and constant global carbon taxes. C1 keeps temperatures below 1.5 °C, whereas C5 results in 2.5 °C. | IPCC AR6 WGIII

To estimate developing world mitigation cost impacts over the century caused by historical emissions, we can take 5% of 80 years worth of economic output and divide it by our historical emissions. This implies that we discount future losses at the same rate as economic growth. Given that developing world GDP is $45 trillion today, these losses amount to $86 per historical ton of CO2 for 1.5 °C and $11 for 2.5 °C.

Uncertainties in mitigation costs

These estimates are also highly uncertain. On the positive side, they do not account for savings of climate damages, which could pay for most or all of the calculated mitigation costs. On the negative side, the mitigation efforts in these modeled scenarios proceed in an idealized manner with optimized technology deployment driven by a uniform global carbon tax. Real-world implementation is likely to be multiple times less efficient.

From our efforts thus far, I’m afraid that the negative effects of inefficient mitigation execution will win out. As reviewed earlier, current efforts based on green technology-forcing and fossil fuel divestment are avoiding CO2 at costs in the hundreds or even thousands of dollars per ton. For example, a single global recession caused by the excessive fossil fuel prices created by the divestment movement will be enough to create the persistent 2.5% loss in economic output assigned to the 1.5 °C scenarios in the IPCC report.

Furthermore, there are many real-world factors that cannot be represented in such models, e.g., inefficiencies and delays from new energy system complexity, critical mineral supply issues, delays and cost escalations from public resistance, reskilling costs, and persistent economic shocks like the current global bout of energy-driven inflation.

All considered, the costs outlined above could be multiple times higher, especially when we constrain ourselves to impossibly tight carbon budgets.

Summary of costs

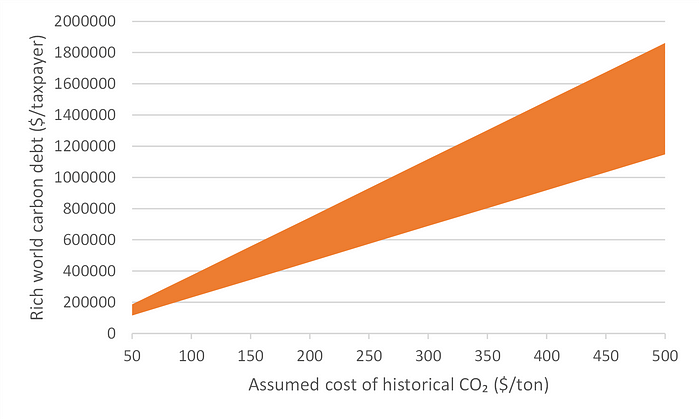

Ultimately, the uncertainty in the valuation of historical emissions is too large to venture a single estimate for our monetary carbon debt. Instead, I present the following graph showing the range of carbon debt as a function of the value placed on each ton of historical emissions.

Estimated rich-world carbon debt per taxpayer depending on the cost assigned to each unit of historical CO2. The lower bound of the range assumes we only take responsibility for our own historical emissions, whereas the upper bound assumes we also take responsibility for half the developing world’s historical emissions.

In general, those who believe climate change is a true existential crisis and we should do everything in our power to reach net-zero by 2050 would put our debt toward the right of the graph above, whereas those who believe climate change is a problem but not a crisis and we can instead aim for 2.5 °C would end up toward the left.

An illuminating hypocrisy check

This wide range of valuations offers an interesting test for rich-world climate crisis hypocrisy. Many rich-world commentators advocate strongly for extreme climate action, often imploring the developing world to rapidly phase out all coal use. Will these commentators put their money where their mouths are?

Given that the historical climate debt aligned with such views likely hovers around $1 million per taxpayer, rich-world climate activists should donate thousands of dollars per month of their own money to the developing world. For example, repaying a $1 million loan with 3% interest over 30 years (the interest accounts for the ongoing damages caused by our historical emissions while the debt is being repaid), requires monthly payments of $4300.

Not doing so would be hypocritical. It would amount to saying that the developing world will face costs amounting to hundreds of dollars per ton of historical CO2 but refusing to take any responsibility for any of that historical CO2 that made our comfortable lives possible.

Why Would We Ever Pay?

Even though it would be hypocritical for any rich-world citizen concerned with climate change not to donate hundreds or even thousands of dollars per month to worthy developing-world causes, there is nothing forcing us to do so. Given our natural talent for sins of omission, is there any chance that even a tiny fraction of our climate debt will ever be paid?

Well, the likelihood may be larger than you think. Some powerful carrots and sticks are steadily emerging to drive us toward virtuous action.

The stick: Pressure from the developing world

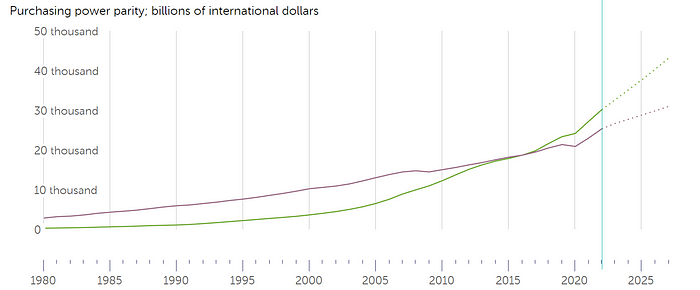

It’s no secret that the center of global power is gradually shifting from West to East, largely due to the Chinese economic miracle. Adjusted for purchasing power parity (correctly accounting for the actual amount of goods and services produced in an economy), Chinese GDP has gone from being a paltry 19% of US GDP in 1990 to fully 119% today.

The Chinese economy (green) has sped past the USA (purple) in recent years | IMF

As Asia gains greater economic power, it will also gain leverage to claim compensation for climate damages from historical emissions. For example, if Asia stopped exporting to the West, we would experience massive shortages in a wide range of electronics, appliances, and, ironically, clean energy equipment like solar panels and batteries. In such an event, conceding to large climate debt payments would be the cheaper option.

A coalition of developing nations has recently demanded $1.3 trillion per year in compensation from the rich world to aid in their climate change mitigation and adaptation efforts. If we value historical CO2 at just 50 $/ton and agree on a 30-year payback period with 3% interest, they have a moral case for claiming double that amount.

Perhaps the most powerful argument the rich world can present against paying its climate debt is that such large transfers can easily be mismanaged and syphoned off by corrupt officials. The developing world will have to present airtight strategies to guarantee developed nations that its climate debt payments are being effectively used to improve as many lives as possible. The developed world has a strong argument to only transfer additional funds if clear proof is presented that previous funds were effectively invested.

Despite this challenge, I think it’s only a matter of time before the developing world gets very serious about climate justice payments. And when it does, the rich world will have little choice but to concede to some uncomfortable terms.

The carrot: A great sense of purpose

My best-guess valuation of historical CO2 comes to about 80 $/ton — 50 $/ton for direct climate damages and an additional 30 $/ton for the economic growth constraints involved in keeping global warming to 2.5 °C. Under these assumptions, we should pay the developing world about $4 trillion per year for the next 30 years.

That may sound like an incredible amount of money, but it actually represents only 7% of current rich-world GDP. And let’s face it, we spend far more than 7% of our economic output on stuff that is utterly useless or even detrimental to our wellbeing (e.g., Problems 2 and 7 covered in this article).

Thus, we could easily afford it. More importantly, though, it will give millions of rich-world citizens a much-needed sense of purpose, something that we (younger generations in particular) are desperately searching for. It’s hard to come up with a purpose nobler than righting the wrongs that made our privilege possible by uplifting billions of lives in the developing world.

Final Thoughts

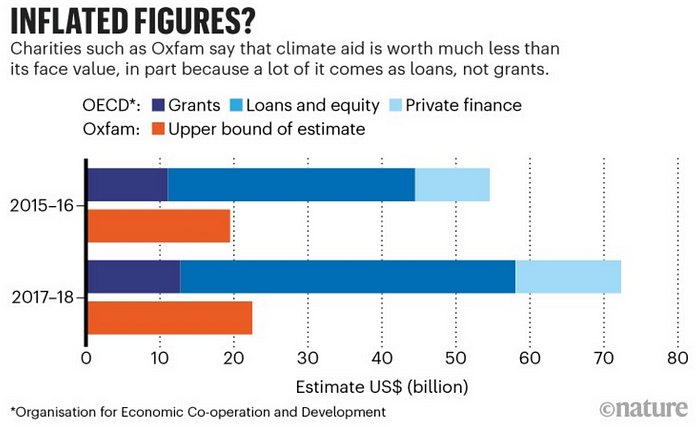

Today, the flow of climate aid from the developed to the developing world amounts to less than 1% of the morally justified amount. Thus, it’s obvious that the world is not yet taking this issue seriously.

Genuine climate aid (which reasonably excludes loans at standard market rates) flowing from developed to developing nations is only about $20 billion per year | Nature

However, things may change rapidly over the coming decade. Thus, I would advise rich-world citizens to position themselves accordingly.

Yes, the paradigm shift from Western consumerism to global altruism is a big and intimidating one, but it can be highly rewarding. In my experience, a sustainable lifestyle brings perfect health and financial freedom, and the vision of a sustainable and equitable global society provides a deep sense of meaning and an even deeper well of inspiration.

Overall, it seems clear that we will need to live far more Efficient Lives in the not-too-distant future. Best to get a head start and learn to enjoy life as a responsible and aware global citizen.

Get Published - Build a Following

The Energy Central Power Industry Network® is based on one core idea - power industry professionals helping each other and advancing the industry by sharing and learning from each other.

If you have an experience or insight to share or have learned something from a conference or seminar, your peers and colleagues on Energy Central want to hear about it. It's also easy to share a link to an article you've liked or an industry resource that you think would be helpful.

Sign in to Participate