Western Australia’s greenhouse gas emissions are rising with little sign that the main power grid can decarbonise rapidly, leaving other states to make bigger cuts if Australia’s legislated carbon reduction goals are to be met.

Modelling results presented to the state government late last year and obtained by Guardian Australia showed that the state’s carbon emissions in 2024 are on track to reach 91.5m tonnes of carbon dioxide-equivalent, or about 20% above 2005 levels.

Australia’s emissions reached 459m tonnes CO2-e in the year to December 2023, according to preliminary federal data. That tally was about 26% below 2005 levels and still well shy of the legislated 43% reduction target.

Unlike others states, WA does not have its own 2030 target. The Labor-led Cook government is considering legislating its goal for 2035 once it sees what the federal government settles on.

One scenario put forward in the modelling by Climateworks and CSIRO had the main power grid serving the bulk of WA’s population reducing 2005-level emissions 2% by 2030 and 20% by 2035 based on present policies. Those “significant emissions reductions” in the South West Interconnected System, would need to overcome “key barriers”, including a lack of transmission capacity.

Brad Pettitt, the sole Greens MP in state parliament, said WA lagged other states even though its government-owned grid offered a means to expedite the take-up other states such as Victoria lacked. Any 2035 goal is unlikely to be agreed by the WA government before 2026 at the earliest.

“We have 10% of Australia’s population but 17% of emissions,” Pettitt said. “We are a huge outlier.

“What’s more disturbing is we have no serious plan to get them down this decade. Nothing is planned at all.”

State-owned Western Power, for instance, takes up to five years to grant approvals for new wind and solar farms to be connected to the grid. Even if they do, developers have to stump up $100,000 per megawatt of capacity to pay for transmission that they then hand over to the state, he said.

WA’s relatively high dependence on the growing mining and gas sector, including downstream processing of raw materials, has resulted in carbon emissions rising even as other states and the federal government introduce policies to cut their pollution.

WA and the Northern Territory are also not connected to the national electricity market that serves most of the rest of the country, with states exporting and importing power between them.

Gas plays a bigger role in WA power supply than elsewhere, making up about 38% of Swis electricity in the wholesale market in the year to last June, ahead of coal’s share of 27%, wind’s 16% and solar farms less than 2%. About 38% of WA homes have rooftop solar, supplying about 15.5% and rising in capacity by about 1 megawatt a day.

A survey commissioned by Pettitt and conducted by the independent analyst Fraser Maywood found that new energy projects in WA – whether under construction or starting operation – had flatlined.

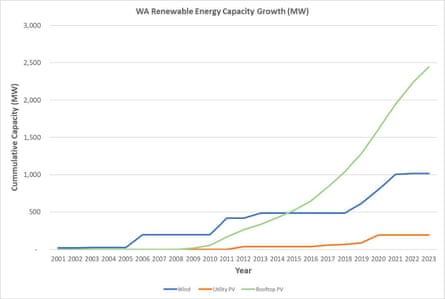

WA has installed 1.2 gigawatts of solar and windfarms in the past 20 years. The government’s own modelling showed WA would need to bring on 50GW of new large-scale renewables – or 63 times the amount of solar and 16 times the wind – by 2042.

“It is abundantly clear that to ramp up renewable energy on a scale that is needed by the government’s own forecasts requires an urgent and dramatic shift in government policy,” the report, obtained by Guardian Australia, found.

The slowdown in the South West Interconnected System project contrasted with the official government position that there were “a large number of renewable energy projects in the pipeline”, it said.

Industry representatives interviewed for the survey identified “significant challenges” such as land and network access by the state grid operations. But they had “a universal fear that voicing these concerns may harm future prospects”.

A government spokesperson did not respond to questions about the modelling but said the state recognised “the need to take urgent action to address climate change” and was committed to achieving net zero emissions by 2050.

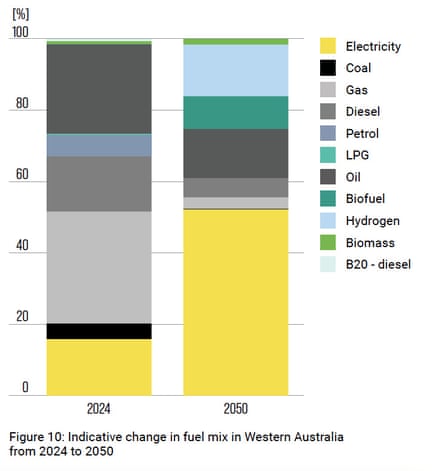

“While our state’s path to net zero will be unique given its economy is supported by hard-to-abate industries, WA is well placed to play a critical a role in the global energy transition as a renewable hydrogen and critical minerals exporter,” the spokesperson said. “Our government’s decision to retire all state-owned coal-fired power plants by 2030 will play a major part in WA’s decarbonisation efforts.

The government had committed to invest more than $3.8bn in wind generation and energy storage, he said. If invested, emissions in the main grid would be cut by 40%.

Pettitt said there was a “real danger” the renewables would not progress on time, resulting in the state instead commissioning more gas-fired power plants.

Other states were already picking up between 20m and 30m tonnes of CO2-e a year because of WA’s outsized emissions. That load could swell even more if WA used more gas.

“These investments aren’t short term and nor are their emissions,” Pettitt said.