Last month’s heatwave in New South Wales and fears of rolling blackouts sparked the usual debate from the usual quarters about how the country’s biggest grid could possibly survive without the country’s biggest coal generator.

The 2.88 GW Eraring facility is scheduled to shut in August next year, less than 18 months away, although there is widespread speculation that owner Origin Energy will cut some sort of underwriting deal with the state government to keep at least two units open for another summer or two.

Many energy analysts argue that such extensions – and costs – are not necessary, particularly if all the planned projects currently under construction are delivered in time.

And to emphasise that point, they have released new analysis on what would have happened on February 29, when the temperature gauge jumped up to 41°C, and the searing heat didn’t just break electricity demand levels, they smashed them.

As we wrote at the time, “native demand” leapt above 15 gigawatt for the first time to reach a peak of 15.6 GW in the mid afternoon – a stunning 730 MW above the previous peak. But we also noted the growth of rooftop solar pushed the peak in “operational demand” to the early evening, and only to its third highest level.

The new analysis assumes what would have happened if Eraring was off line, and new wind, solar, battery and virtual power plant projects had been delivered on schedule.

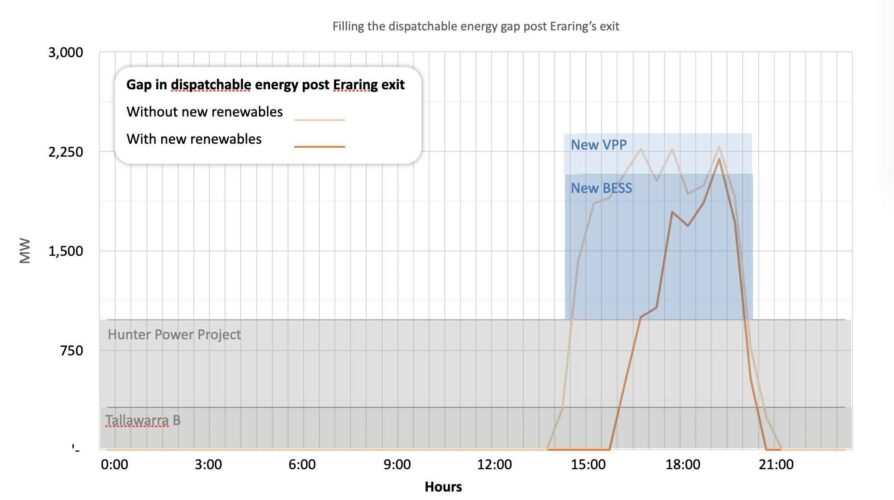

This graph above illustrates – in the bold and light orange lines – the “dispatchable energy gap” that would have appeared on February 29, had Eraring not been operating. The demand levels have been adjusted to account for the forecast 3.5 per cent annual increase in demand anticipated by AEMO between now and Eraring’s closure.

The first thing to notice is that for most of the day there is no energy gap, until the heat takes effect and the air-con ramps up in the early afternoon.

With no new generation and storage, a yawning gap (represented in the light orange line) emerges around 2.30pm and quickly leaps towards 2GW, where it stays until around 8pm when temperatures have eased.

The analysis shows that the near five gigawatts of new renewables will push that yawning gap back into the later afternoon by around 2 hours until 4pm, and significantly reduce the scale of the gap it until after 7pm (see bright orange line).

These new renewables will comprise six big solar farms, including Stubbo, New England 2, and the newly contracted Culcairn project, totalling 2.4 GW, plus three new wind farms totalling 820 MW, including Uungala, Flyers Creek and Coppabella. There will also be an estimated 1.7 GW more rooftop solar.

The rest of the energy gap (in grey blocks) is filled by dispatchable generation, firstly by the newly commissioned 320 MW Tallwarra B gas plant owned by EnergyAustralia, and the 660 MW Kurri Kurri gas generator currently being built by Snowy Hydro.

In blue, there will also be eight new batteries totalling 2.5 GW and 6.5 GWh, including the massive Waratah Super battery at 850 MW and 1650 MWh, the 415 MW, four hour Orana battery, the 500 MW, two hour Liddell battery and the 460 MW, two hour Eraring battery.

The list also includes the country’s, and probably the world’s, first eight hour battery, the 50 MW, 400 MWh Limondale facility to be built by German energy giant RWE.

And there will be capacity from virtual power plants, including 90 MW from a newly contracted project put forward by EnelX, and a promised 826 MW increase from Origin’s own efforts to boost its VPP capacity, called Origin loop.

Tim Buckley, from Climate Energy Finance, says there will also be new capacity that could be sourced from the new transmission line, Project EnergyConnect, that links the state to South Australia.

Buckley says even more capacity could be delivered from more commercial and industrial solar (and battery) capacity if that sector is encouraged.

“Our analysis shows that there is more than enough capacity to fill the gap on the phased closure of Eraring,” Buckley says, emphasising that the four Eraring units should not be closed all at once, maybe two units before the current scheduled closure and another two units a few months later.

But it underlines the importance that NSW need to make sure the planning processes, and the delivery of new projects, do not throw up more delays. “We’ve got to make sure we don’t have a recurrence of this problem when the next coal fired generator, Vales Point, closes two years later,” Buckley says.

Stephanie Bashir, from Nexa Advisory, says the analysis shows that the state’s energy supply “will be just fine as long as we do what we say we will do.”

She also wants NSW to speed up its planning processes, noting that it is close to the back of the pack in rolling out large-scale renewable energy projects.

“The planning approval process in NSW is 2-3 times slower than other states, adding 4-7 years to project progression and 25 times more expensive for developers compared to an equivalent project than in Queensland,” Bashir says.

“Delaying the closure of ageing coal-fired power stations, such as Eraring, to shore up power supply reliability in the near term will result in higher costs and emissions over the long term. The better approach would be to accelerate the rate at which we deploy new clean energy resources.”

Bashir also advocates dialling in more insurance by extending demand response schemes (DSP) that could encourage big industrial users to dial down their energy demand at critical times, to reduce the risk of outages and ensure that air-con, fridges and other essential services remain switched on.

“DSP is a lower cost resource than supply-side capacity because it utilises the capability of existing assets,” she says. “The capex required to activate 1,000 MW of DSP capacity in NSW is a fraction of what is required to build 1,000 MW of supply-side capacity.”

Others suggest that the Eraring situation also underlines their belief that coal closures should not be based around fixed dates, but by when the replacement capacity is actually built.

This would help takes the politics out of the equation, because one of the things troubling the NSW government is the next election set down for early 2027 – and they won’t want power outages, or big price spikes – as a result of the closure.

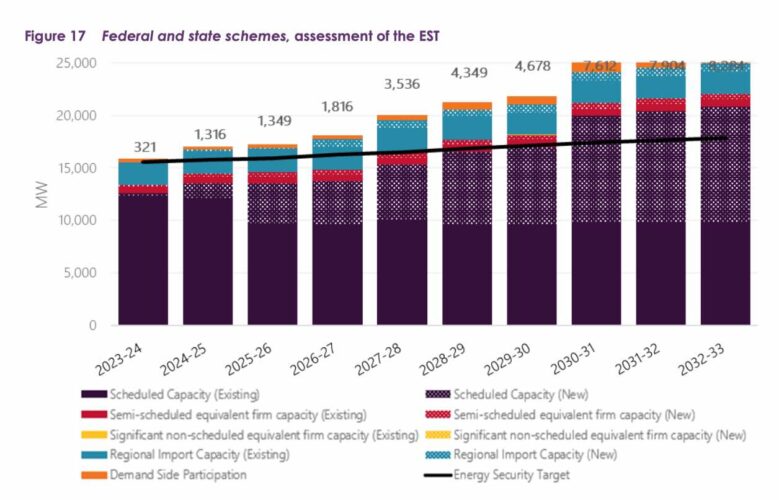

The assessment by the team led by Buckley and Bashir broadly concurs with the Australian Energy Market Operator’s own updated assessment, made in October last year, which suggested that the latest tenders under the expanded Capital Investment Scheme will deliver enough capacity in NSW.

The AEMO assessment warns, though, that this assessment changes and gaps would emerge if there are delays to these projects, and if there is insufficient “co-ordination” of consumer energy resources, which includes rooftop solar and battery storage.