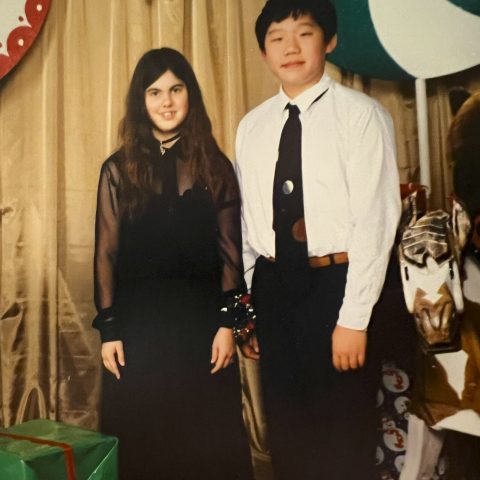

take photos at a holiday-themed high school dance.

Besides being Earth Month and National Arab-American Heritage Month, April is also Autism Acceptance Month. What does and what should that mean for climate and environmental justice? Let me start by telling you about an old friend of mine:

Four years ago this month, my high school friend Mel Baggs (sie/hir/hirs)—a queer, nonbinary member of the developmental disability self-advocacy movement and an influential autism and disability justice activist in the early days of the internet—passed away. Sie attended my high school for less than a full academic year, but it was during this brief time that we became good friends.

In hir activism, Mel advanced the notion of autistic pride and self-advocacy, in direct opposition to organizations like Autism Speaks, whose original stated aims were to “heal” or “fix” autistic people. If you were on YouTube in its early days, you might remember “In My Language”—Mel’s video that went viral on the platform in 2007. Sie advanced the notion that disabled and neurodivergent people don’t need fixing—they need acceptance and systemic changes that would allow them to live independent lives in a society built by and for able-bodied and neurotypical people.

Every time April rolls around now, I think about how Mel passed away during the very beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, and how hir inability to access personal care assistance (which was classed as a nonessential service during that turbulent time) may have hastened hir death. The Autistic Self-Advocacy Network (ASAN), an organization I remember Mel supporting over the years, had this to say on the subject:

Over the last few years, Mel documented hir struggles with a service system that would not meet hir independent living needs... It is a massive systems failure that Mel’s needs went unmet in hir last years. Sie deserved so much better. (ASAN, 2020)

I’m not here to dwell on how Mel passed away, though. In a eulogy for Mel, Sara Luterman wrote, “Mel’s death does not belong to me. I will not try to imbue it with meaning. Mel’s death is hir own.”

Where Are the Intersections?

What I do want to talk about is disability justice—and in particular, a few of the many ways that it intersects with climate and environmental justice. I also want to say that I am in no way an expert, and that I’m writing on this topic as an able-bodied person, so you should view what I’m about to write within that context. But here’s what I’ve learned, and what I’d like to share with you all:

Globally, it’s estimated that about one in six people—about 1.3 billion people globally—experience a significant disability. It’s imperative that we take disability justice seriously if we are to advance a Just Transition that leaves no one on the frontlines behind.

Environmental inequities, such as persistent pollution in frontline communities, don’t just lead to poor health outcomes. They can disable people.

We know, for instance, that it’s mainly communities of color and people with lower incomes living in places that are disproportionately affected by pollution.

According to a 2018 study in the Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, British researchers found that children with intellectual disabilities were “33 percent more likely to live in areas with high levels of diesel particulate matter, 30 percent more likely to live in areas with high levels of nitrogen dioxide, 30 percent more likely to live in areas with high levels of carbon monoxide, and 17 percent more likely to live in areas with high levels of sulphur dioxide.”

More recently and locally, a University of Washington study found that children were more likely to exhibit impairments to behavioral functioning and cognitive performance when their mothers experienced higher exposures to nitrogen dioxide and small-particle air pollution.

Whether it’s a pandemic or climate change, in times of crisis, disabled people are at risk of being left behind.

There is quite a lot of research and analysis out there showing how disabled people were less likely to receive care and more likely to die during the height of the pandemic. In the event of a disaster, including climate disasters, disabled people are four times more likely to die.

But these discrepancies in health and mortality don’t exist because some people are disabled—they exist because we have systems in place that don’t value the lives of disabled people. For example, while there is a 10- to 20-year discrepancy in life expectancy between disabled and able-bodied people around the world, that discrepancy is fueled by the fact that disabled people are three times likelier to be denied access to healthcare.

Ultimately, disability justice, climate justice, and environmental justice are all movements advancing the principle that the lives of frontline communities—communities of color, Indigenous peoples, 2SLGBTQIA+ people, disabled people, people with low incomes, immigrants and refugees—matter.

Current, longstanding inequities exist because our lives have been devalued by those in power, and our movements for justice are here to correct that.

Mel left us with multiple, different blogs that showcase hir writings and creative work, but arguably hir most well-known platform was Ballastexistenz. In 2013, sie explained:

Ballastexistenz is a historical term that means “ballast existence” or “ballast life,” that was applied to disabled people in order to make us seem like useless eaters, lives unworthy of life. I knew when I started this blog that this was how many people perceived me, but I have since experienced levels of discrimination, particularly in the field of medical care, that would have killed me outright had I not had a strong disability community fighting for me.

In the eyes of the medical profession, I’ve become even more of a ballastexistenz than I used to be, ever since I got my feeding tube last year. I had no idea that once you got a feeding tube, you crossed a line into a category of people that are seen as being “artificially kept alive.” People who maybe shouldn’t be kept alive. Have you ever heard someone say, “We have the technology to keep people alive too long these days”? Said it yourself? People on feeding tubes, people on ventilators, we all have to contend with this idea that maybe we shouldn’t be here. Maybe we’re a waste of resources that could be better used on people who really matter.

Make no mistake about this: I love my feeding tube with a passion... Now I can eat exactly as much as I need to, by pumping Osmolite directly into my intestines, bypassing my semi-paralyzed stomach. This is all wonderful and allows me to experience life in all its amazing beauty. Nobody can ever tell me that I’ve been kept alive too long.

A Just Transition to a carbon-free future must address and dismantle systemic barriers that exclude disabled and neurodivergent folks from climate solutions.

A few years ago, the Journal of Environmental Psychology published a study that explored the question as to whether or not autistic traits predicted pro-environmental attitudes and behaviors, as well as climate change belief. The short answer is that while the authors found no such connection, they did say that significant barriers make the transition to a carbon-free future much more difficult for disabled and neurodivergent folks.

At Front and Centered, we’ve thankful to have had the opportunity to build out our Transportation Justice work, such as our Transportation Bill of Rights or our more recent work on Washington State’s Transportation Electrification Strategy, in collaboration with advocates for mobility justice like Disability Rights Washington and Empower Movement Washington. The transition to a carbon-free, just future we need requires changing outdated practices and removing systemic obstacles that exclude the knowledges and experiences of disabled and neurodivergent folks and prevent them from being independent participants and leaders in decision-making spaces.

A few years ago, while writing about how Greta Thunberg’s autism is often weaponized in order to discredit her climate activism, Lydia X. Z. Brown said: “When people say they can’t believe I am autistic, they mean it as a compliment. But the comment is really a backhanded insult, rooted in the fact that society defines disabled people as incompetent, inferior, and permanently infantile… Thunberg is a powerful and visionary leader not despite her youth, gender, disability, or anger—but in large part because she is a young autistic woman rightfully angry about the repeated failures and refusals of people with the power to reverse our oncoming climate catastrophe to do so.”

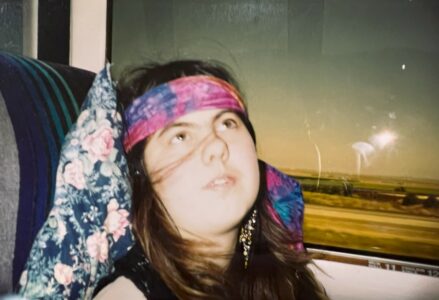

I often think about how Mel would engage with the climate and environmental justice movements if sie had managed to survive a system that devalues disabled people. Mel was the first person with whom I could have conversations about religion and philosophy. Sie introduced me to the Cocteau Twins, which would permanently reshape my musical tastes. We went to a school holiday dance together, and we walked to a local deli before the dance to eat pesto pasta. We took Latin and went to Junior Classical League conventions, and sie would pass me notes in class to tell me about hir connection to the redwoods in hir home in Santa Cruz. Sie encouraged my interest in creative writing, ultimately influencing my journey to working in communications. I’ll be playing this song for hir today: