A young girl, home alone, wakes up in the middle of the night and walks over to her neighbor’s house. She opens the front door and encounters a horrific scene: a zombified grandma committing an act of cannibalism. Instead of teeth in the woman’s mouth, it’s long tendrils of fungus.

That’s one of the first scenes in The Last of Us, the HBO show about a global fungal pandemic that gripped viewers this past winter. The premise is pure fiction. The fungus depicted in the show, cordyceps, is harmless to humans. But the world’s susceptibility to fungal pathogens is genuine. When the real fungal pandemic comes, it won’t look like anything you’ve seen on screen.

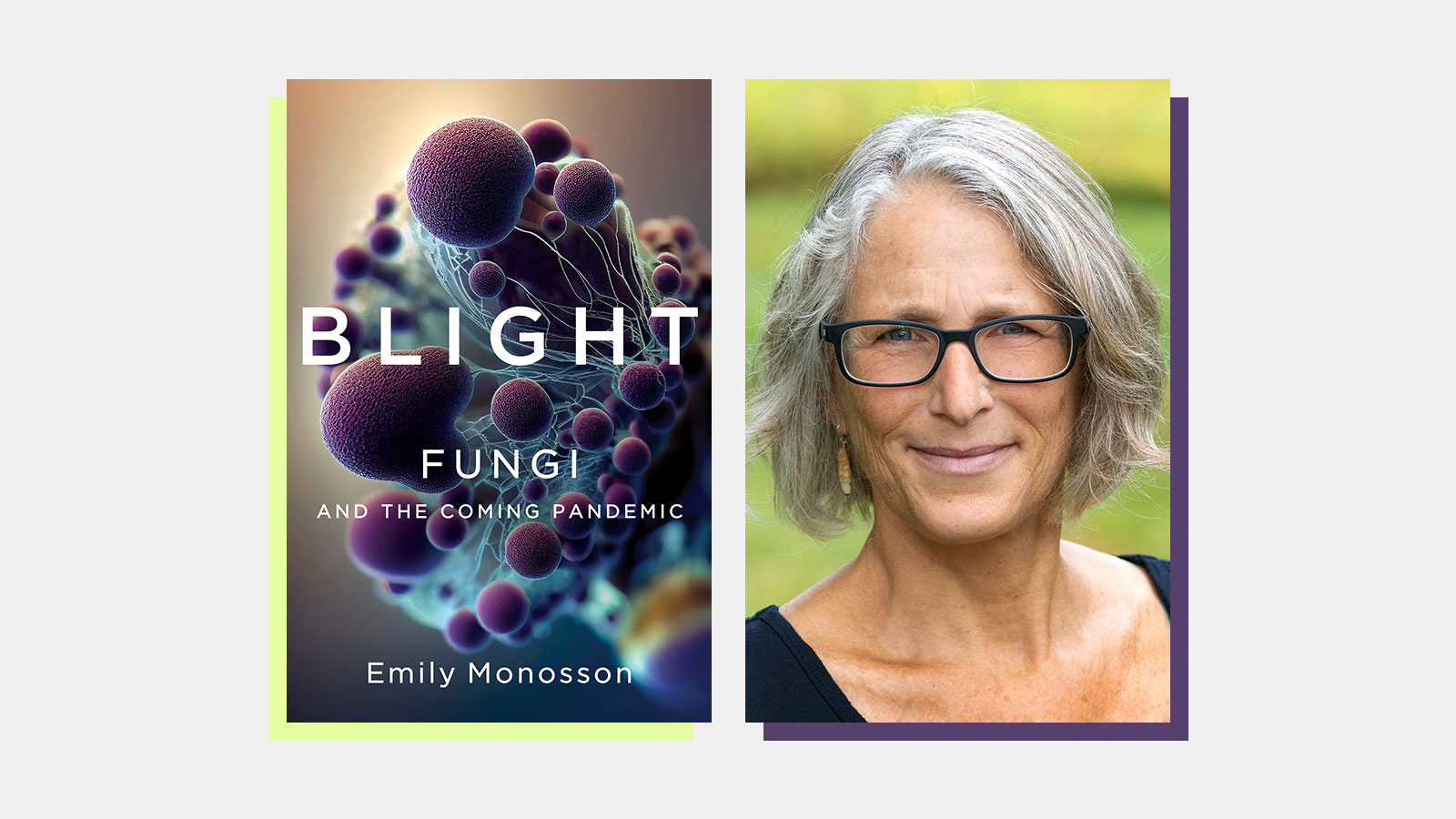

In her new book Blight: Fungi and the Coming Pandemic, author, professor, and researcher Emily Monosson unravels the expansive and unsettling history of fungal invasions across the globe and how they have shaped our lives in both visible and invisible ways. A fungus called batrachochytrium dendrobatidis, or Bd, has wiped out more than 200 species of frogs and other amphibians. White-nose syndrome, a fungal illness in bats, has killed millions of the winged critters across North America. A fungal pathogen wiped out the world’s most popular banana, the Gros Michel, in the first half of the 20th century. Fungi are now coming for the Cavendish, the banana we bred to replace the bananas we lost.

And, of course, fungi threaten humans, too — not just by decimating the biodiversity of the world around us, but also by infiltrating our bodies and causing new illnesses. Candida auris, a drug-resistant yeast, emerged in 2009 on three continents simultaneously. The disease, Monosson writes in her book, “seemed to come from nowhere and everywhere at once.” C. auris quickly started claiming lives, particularly in hospital settings, where it preys on the immunocompromised. The pathogen kills roughly one-third of hospitalized patients, according to an analysis of hospital data collected between 2017 and 2022, and that’s likely an underestimate.

Some researchers theorize that C. auris has always lived among us, unable to survive inside the human body due to our species’ high internal temperature. But as global temperatures have risen over the decades, the fungus may have evolved to adapt to a warmer climate. Climate change, the theory goes, has trained C. auris how to infiltrate our bodies. And global warming could help other fungal pathogens spread, too.

“Over the past century fungal infections have caused catastrophic losses in other species, but so far we have been lucky,” Monosson writes. “Our luck may be running out.” She calls for better prevention measures — regulations on the import of foreign flora and fauna, better testing technologies for plants and animals that cross borders, and more funding for conservation work that protects wild species in their existing habitats. Blight: Fungi and the Coming Pandemic is available this week in bookstores and libraries.

This Q&A has been edited and condensed for clarity and length.

Q.Readers might pick up your book and assume it is entirely focused on the impact of fungal disease on human health. But Blight is about so much more. Can you speak to your approach here? What overarching story were you trying to tell?

A.The thing that got me started thinking about the book was a paper that was written years ago by a group of different scientists across disciplines. They were in medicine, ecology, agriculture, and a few others. That’s kind of unusual, to see a review written by so many different scientists. The focus of the paper was fungi, and they were trying to get people more aware. They felt that people didn’t really appreciate the potential consequences of large fungal infections.

For a lot of us, once in a while in the news we’ll hear, “Oh, we’re not going to have our bananas anymore,” or “The frogs are dying,” or “The bats are dying.” But you hear those warnings and then it goes out of the news cycle and seems like, oh, OK that was a weird thing.

If you talk to somebody who’s in any of these fields, you’ll see that it’s not so odd that this is happening, because fungal pathogens can be really catastrophic when they strike. So the purpose of the book was to put all of this together, to say that these aren’t just one-offs. We need to think about the potential of fungal pathogens and the breadth of impact that they have across species.

Q.Blight is about fungi, yes, but it’s also about facets of modern life that researchers have been worried about for quite some time — globalization, biosecurity, climate change. How are all of these things connected?

A.The first epidemics and pandemics that I write about, the decline of the chestnut and pine blister rust in forests, started about 100 years ago. And for forever before that there were fungal pathogens in agriculture —- probably ever since humans started doing agriculture. But most of the book focuses on the past 100 years. And that’s because there’s been an increase in fungal pandemics or epidemics across species in the last 100 years. That’s because we have been moving plants and animals around, and ourselves around, at a rate that is really unprecedented in our long history on Earth.

Every time you move something around, there’s all sorts of other things on them. And when we take them to another place, they have the opportunity to find a new host. And if that host is susceptible, then you’ve got a problem. So between trade, travel, and the changing climate that you mentioned, there’s potential for fungi to adapt to changes in crops and agriculture, and adapt to warmer temperatures and drought conditions faster than, say, a crop can. Fungi are adaptable. And there’s a pretty good chance that fungi will be able to adapt to a changing temperature or changing climate.

Q.This book is publishing at a moment when a lot of people are thinking about pathogenic fungi thanks to recent news reports about Candida auris and the success of The Last of Us. Cordyceps is a harmless fungus, but there are very real fungal threats out there. Can you talk about Candida auris and why you chose to feature it in the beginning of your book?

A.To be honest, I hoped that Candida auris might draw readers in and then they’d read about all the other problems across other species. But it is also one of the newest emergent fungal diseases. It was kind of unknown until 2009 or 2010, and then the CDC issued its first warning about Candida auris in 2016. So it’s really pretty new, and we don’t often get a really new emergence, except for something like COVID. But COVID is viral — that’s almost to be expected. To have a newly emergent fungal pathogen was something different.

What was most interesting about Candida auris, and I think what was most frightening to public health workers and doctors, is that it emerged in many different places at once, within a couple of years. And when it emerged, it was different strains of the fungus, which means that it wasn’t like COVID where it could be traced back to one single origin strain. So that was something odd, and I don’t think anyone really knows why.

One thought is maybe climate change: Maybe this fungus was just out living in the environment, as many do, and not bothering us. And it couldn’t really survive in our warmer bodies. It didn’t tolerate our internal temperature. But with warmer and warmer days over time, that fungus eventually evolved to be able to tolerate our temperature and could live in us. And when it did, it became a problem.

I should qualify that humans are pretty well protected against fungal pathogens. We have our temperature, for one, but we also have a pretty robust immune system that can fend off most fungi. We’re all breathing spores right now. And for most of us, it’s not a problem. But if you’re immunocompromised, and there are a growing number of people who are immunocompromised, then the threat of a fungal pathogen is more important.

Q.You’ve written books on a number of topics, including chemicals, genes, and germs. Why did you choose to focus on fungi this time?

A.It was a personal experience of having a fungus-like organism kill my tomatoes. Just seeing that happen, I got interested in it. So I thought I’d write a little article about it. And that’s around the same time that paper I mentioned came out. It was curiosity at first, because I didn’t really think about fungal pathogens back then.

I started this in 2019, before COVID. When it was clear that COVID was something really big and bad, I actually emailed my editor and I was like, “Should I keep writing this? Because who is going to want to read about a pandemic after we get through this pandemic?”

Q.But you kept going. Is that because there’s light at the end of the tunnel?

A.I think the hopeful thing is there’s a lot of really passionate scientists working on these problems. We should support them, the policies that may come out of the science, the conservation organizations that are trying to do prevention work. Really the goal here is prevention, and that involves all of us.

We need to take responsibility for our actions. I know that’s trite. But maybe if we are even a little more thoughtful about how we do things, what we think we “need” in our lives, and how that impacts the world around us — we might do less harm to the natural world and to other humans.