Older Jakartans would remember the 1963 Lilis Suryani song ‘Gang Kelinci’ (Rabbit Alley): people are multiplying in the city like rabbits, she sings.

Jakarta has always been crowded, but now hundreds of child-friendly community centres are giving people a healthy, outdoor place to go and providing vital support for their physical and mental well-being.

A megacity, Jakarta faces traffic congestion, housing, waste collection, water supply, and drainage and flooding problems. The metropolitan area, home to 30 million people, has large pockets of informal settlements and extremely high population density.

Tambora district (Kecamatan) in West Jakarta is the most densely populated area in Southeast Asia. In 2021 it squeezed 50,627 people into every square kilometre. The area is filled with high-rise settlements where public space is non-existent. In the tiny dwellings the same areas are used for various activities from cooking to sleeping. Most residents need to take turns to sleep and sometimes have to sleep with their legs crossed due to the very limited space.

Keeping apart from others to help manage COVID-19 is impossible here. Tambora residents simply do not have the luxury of staying indoors for 24 hours a day in their two-storey, 6-by-12-metre houses shared with 23 other people.

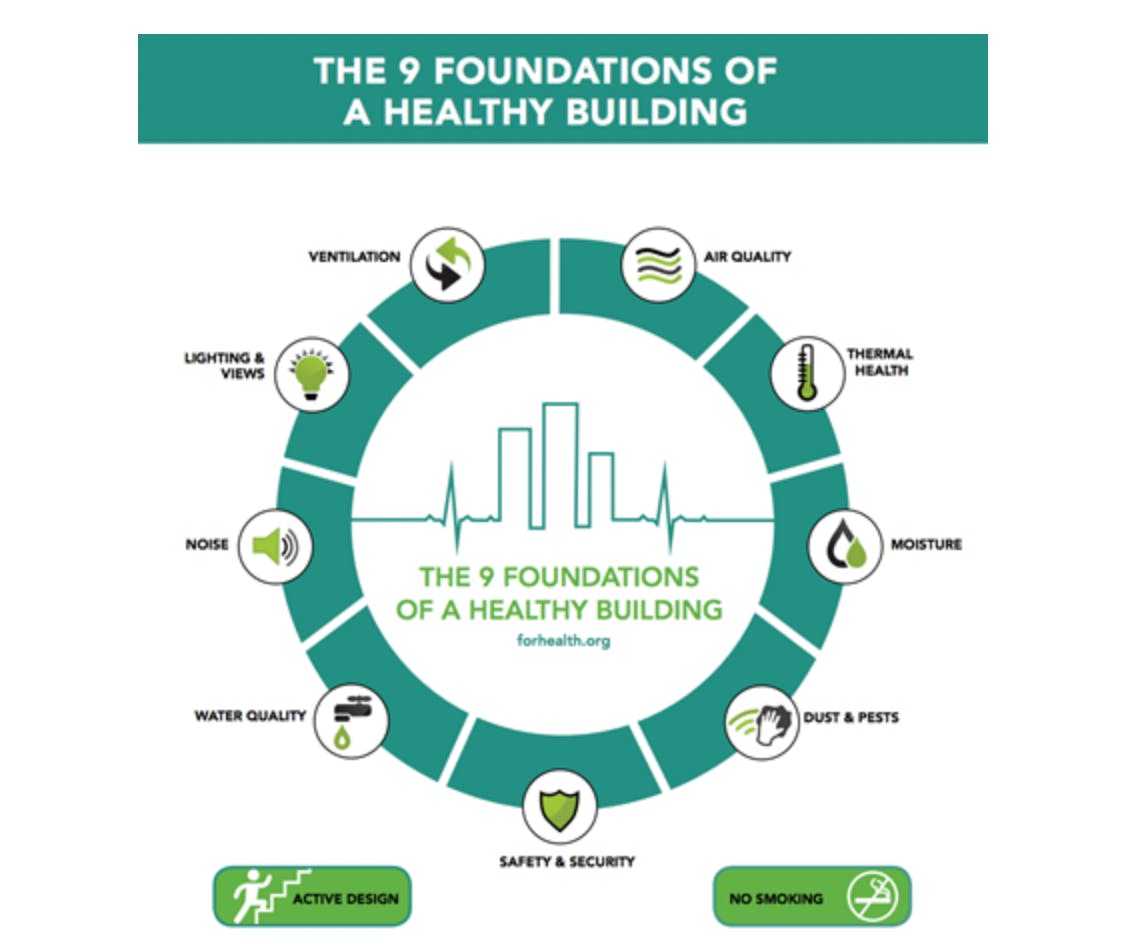

Venus Alley in Tambora never sees daylight: it is dark and overcrowded, and the people who live here have limited access to clean water and fresh air. These living conditions, meeting none of the nine foundations of a healthy building, have profound effects on people’s mental health.

9 foundations for a health building. Source: Harvard T.H. Chan School for Public Health: forhealth.org

Poor ventilation leads to low air quality, which reduces well-being. It also means a house is unlikely to be at a comfortable temperature. This leads to sick building syndrome, which is linked to low mood.

Lack of natural light causes sleep problems and symptoms of depression.

To combat these problems, the Jakarta government has established a series of public Child-Friendly Community Centres (RPTRAs). The centres support Jakartans’ mental health by providing open space and an alternative place to go. This alternative is especially important for residents of crowded high-rise communities such as Tambora.

There are 289 centres across the city, most located in very crowded areas. They have become places for different age groups to gather and pursue healthy activities. Some centres have communal gardens, providing the many benefits of urban agriculture. Local people can grow their own vegetables and enjoy beautiful views and healthier surroundings. The centres green the city and empower the community to improve their physical and mental health.

In Tambora, the 2.692 square-metre RPTRA Krendang centre has futsal and basketball fields, a community centre, a communal garden and a children’s playground. People use the space for urban farming, community gatherings and sport. The centre has become a retreat for fostering mental health. During the worst of the pandemic, this public area was the only breathable space away from the crowded houses.

Studies tend to show a link between green-space exposure, physical activity and improved mental well-being in women. Access to green space has also been found to improve mental well-being in men.

A city is not sustainable unless its residents are resilient and healthy. Jakarta faces many challenges in making all its buildings healthy places to live, but in the meantime easier access to open space is helping to improve community mental health.

Eka Permanasari is an adjunct Associate Professor at Monash Art, Design and Architecture, Monash University Australia. She has led international research such as Cross-cultural Community-based Strategies for Sustainable Urban Streams in Des moines and Jakarta, as well as the impact of the new Indonesian capital to the communities and surrounding cities. Apart from being a researcher she also led several strategic national projects for the Jakarta government, such as the Giant Sea Wall Jakarta coastal development, six community-centre pilot projects (RPTRA), as well as the revitalization of public housings in Kemayoran and Klender.

Dr Permanasari declared that she has no conflict of interest and is not receiving specific funding in any form.

Originally published under Creative Commons by 360info.