One man’s dung is another man’s treasure…or so it would seem to ecologist and entomologist Dr Eleanor Slade, who specialises in the study of dung beetles and the information they offer about the health and biodiversity of tropical forests.

Slade, who is assistant professor of forest invertebrate ecology at Nanyang Technological University, Singapore, was one of 48 scientists who participated in a two-week scientific expedition at the Sekar Imej Conservation Area in the Beluran district of Sabah, Malaysia. The expedition aimed at collecting baseline data on the number and types of flora and fauna present in the 2,469-hectare conservation area and involved researchers from the South East Asia Rainforest Research Partnership (SEARRP), Universiti Malaysia Sabah and Universiti Sains Malaysia.

In addition to dung beetles, other insects studied by researchers at Sekar Imej included termites, ants, carrion-eating butterflies and dragonflies. These insects form the crucial base of the food chain as they are eaten by frogs, birds and other mammals, Slade explained.

A hanging dung beetle trap installed in the Sekar Imej Conservation Area. Image: Lim Sheng Haw

She said that dung beetles play a crucial role in the rainforest by burying dung from mammals in the soil, allowing the waste to break down more quickly into nutrients such as nitrogen and carbon.

A healthy and diverse presence of dung beetles species can also tell scientists about the health of the animal population in forests, as different species of bettles feed on the manure of different animals, Slade explained.

In addition to working independently with SEARRP at Sekar Imej, Slade worked closely with fellow entomologist Dr Chiew Li Yuen from University Malaysia Sabah and several research assistants.

Here’s what a day in the field for Slade and her team looks like:

5:30am

Slade: We wake up when the generator comes on and have breakfast.

7:00am

Slade: After breakfast, we prepare the bait for the dung beetle traps. Since we’re here in the camp with other people, we need to go around asking people for “donations” [of human excrement] to be used as bait. We then need to set the bait in the traps.

Chiew: The number of traps we can set up depends on the “donations” of bait we get at the start of the day. On the first day we only set up four traps. Today [the second day of the expedition] we got a good amount of bait and could set up more.

8.00am

Slade: Our team of seven people leave for the forest, including our local guides. Since we didn’t know how far the trail actually was, we hiked all the way to the top of the hill (Monjuk peak) and then started setting traps on our way down.

As you move up the gradients of the hill, you get changes in the animal communities. The sample here [at the base camp closer to the foot of the hill] is more disturbed. As you go up to the peak, you should get less disturbed forests.

Slade explains that the ground level traps for dung beetles must be level with the ground so that the insects can fall into the trap. Image: Samantha Ho/Eco-Business

9:30am

Slade: We begin setting the dung beetle traps, which were designed by one of our team members, Alex, and created using common materials such as plastic bottles.

Because this is a new site, we need to kill the captured beetles to make a reference collection from which we can take DNA samples to identify them. So we fill these traps with a solution of water and a little bit of soap, which breaks the tension of the water so that the beetle doesn’t swim on the surface. We also put in a bit of salt to preserve the carcasses so that they don’t rot.

If we want to capture them alive instead, we put some leaves at the bottom instead of the solution and a funnel at the top to prevent them from escaping.

9:45am

Slade: The traps are set up every 200 metres. We set them this far apart because we want each trap to be independent.

Previously, scientists would set up traps every 50 metres, but they was found that this was too close because beetles could move from one trap to another very quickly. Also, if the traps are too close together, the smells of the bait interfere with each other.

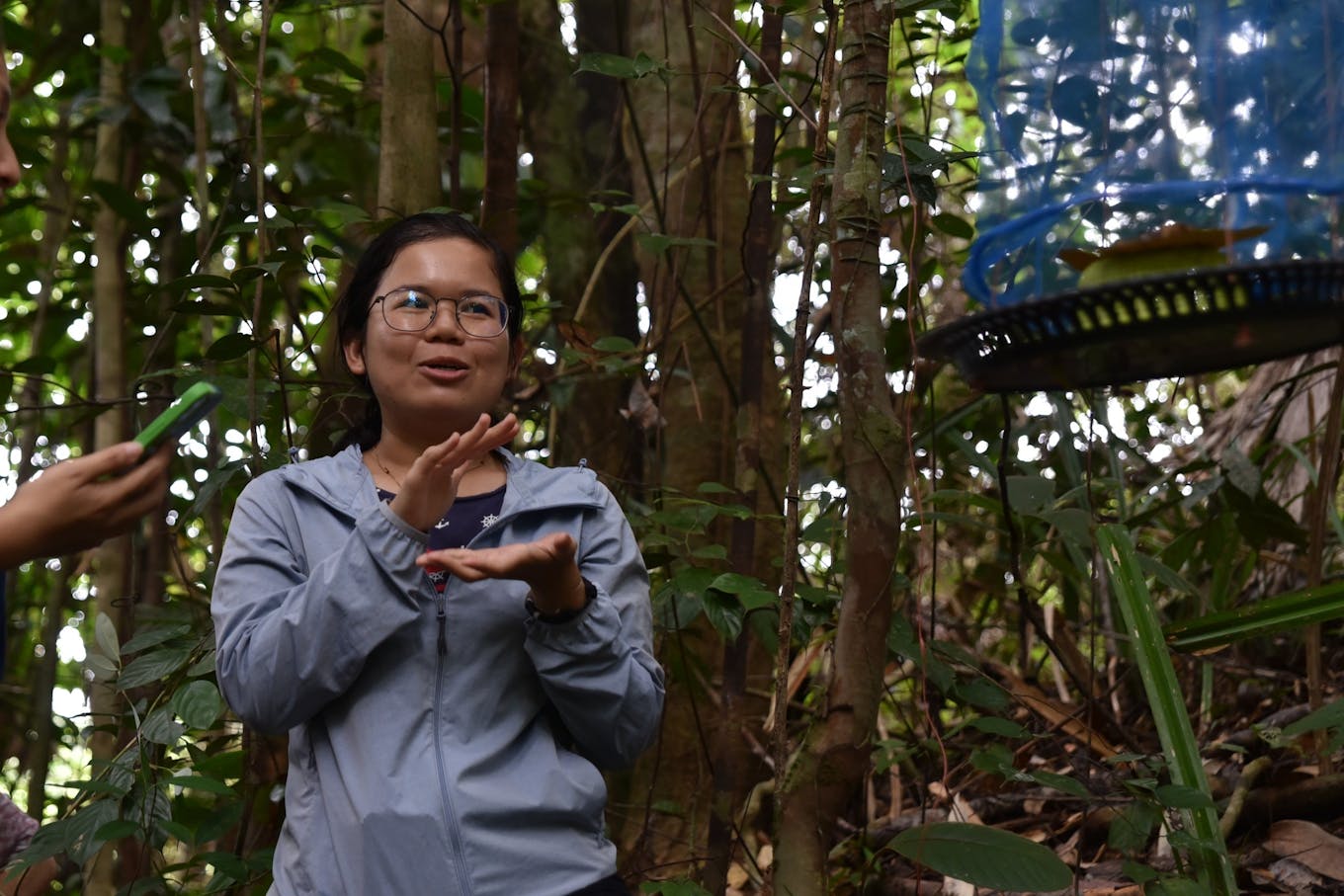

Chiew: Nearby these dung beetle traps, we also set butterfly traps. Those are baited using rotten banana with belacan (shrimp paste). The butterflies are attracted to the food and get trapped when they fly upwards in the net. Then they fly around inside the trap [until we release them].

There are a few dung beetles that are actually fruit feeders as well. So we also come across them the butterfly traps.

12pm

Slade: We break for lunch, which we had packed and carried with us on the trail, and then continue setting up the insect traps.

Chiew explains how carrion-eating butterflies are attracted to the smell of belacan, or shrimp paste in the trap. Image: Lim Sheng Haw

2:30pm

Chiew: We arrive back at the base camp and begin capturing dragonflies.

Slade: For the dragonflies, we walked along the river here [next to the basecamp], since they’re mostly found near the rivers. So we weren’t surveying along the same trail [as the dung beetles and butterflies].

We just sweep them up in the nets [attached to long poles], capture, hold them, identify them and take photos, before we release them back into the wild.

5:00pm

Chiew: We took some time to shower and rest for a bit before we held our debriefing for the day.

Slade: We spent a long time trying to identify the dragonfly species that we captured using one of our books, because some of the species we found are not listed in the book. It has some photos and drawings but they don’t overlap, so It’s not a great book to use for identification. So we spent a lot of time making notes for all the dragonflies.

[At the Sekar Imej Conservation Area, which is surrounded by hectares of oil palm plantations, researchers at the base camp did not have internet access for the duration of their stay.]

7:00pm

Slade: We had dinner at around this time. The guys were playing cards while I was trying to learn Malay from Li Yuen. I wanted to head to bed at about 7:30pm, but the rest of them were like, that’s so early!

Chiew: Yes, the rest of us only slept at around 9:00 pm.

Media access to the sponsored Sekar Imej Conservation Area was facilitated by Wilmar, in collaboration with SEARRP.