While it’s too soon to draw strong conclusions in a nascent program, given back-to-back summers of historically high gas prices there is considerable interest in discerning how much the Climate Commitment Act (CCA) contributes to prices paid by consumers at the gas pump. Clean & Prosperous Institute (CaPI) believes it’s important to establish a baseline expectation as we continue to monitor the evolution of allowance prices and compliance costs.

The majority of compliance obligation falls on transportation fuel suppliers. Transportation fuels are the number one emissions source in Washington state, while many of the other emissions in the program are allocated free allowances for various reasons. Consumer cost impacts are, therefore, most likely to show up at the gas pump. The extent to which those costs are passed-through is complex and hard to isolate.

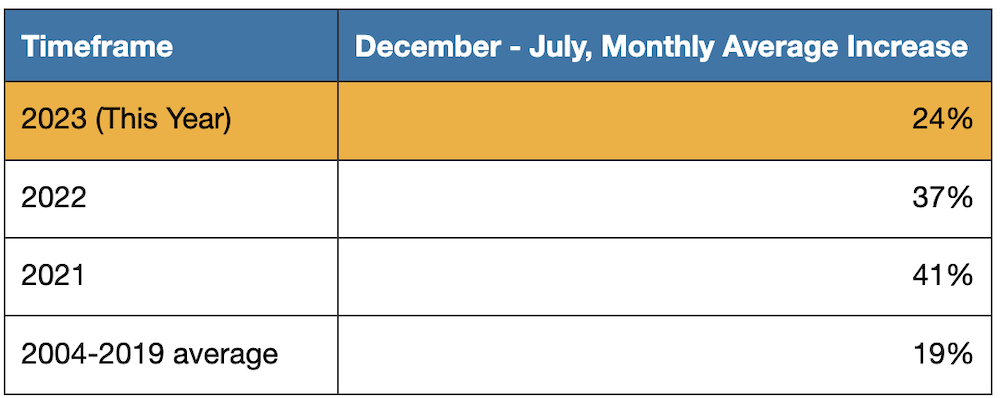

In this article, we present our findings of an average $0.27/gallon as the best estimate to-date for the impact of the CCA based on a comparison of changing gas prices relative to Oregon. This represents partial pass-through to the pump. Full pass-through, based on $53.32 average for non-consigned allowance prices, would translate to $0.42/gallon. While overall gas prices have risen more than $1/gallon from winter to summer of this year, the CCA appears to be a small share of this price increase with most of the increase attributable to an annual pattern of winter-summer price increases (see table below). Holding the CCA responsible for all or even most of gasoline price increases is not supported by real-world data.

Source: Clean and Prosperous Institute analysis using EIA price data (https://www.eia.gov/petroleum/gasdiesel/)

Allowance prices, determined by private entities competing in the market, fluctuate based on assessments of decarbonization costs. Translating allowance prices directly to pump prices is an oversimplification that most likely overstates the program impact. Why is this?

- Unlike a carbon tax, the cap is carried out in four-year windows known as compliance periods rather than as payment due in close alignment with consumption or delivery of fuel. Allowances held retain value as assets until they are retired, and full compliance isn’t due until November 2027, which is over 4 years from today. This offers flexibility for entities to comply in the most cost-effective manner across the market of covered entities. To drive this point home, consider that only 30% of this year’s covered fuel requires compliance by the first compliance deadline in November 2024.

- The majority, 70%, of this year’s fuel requires compliance in November 2027. Additionally, that compliance can be met with allowances purchased in the “future vintage” auctions (May and November), which are designated as 2026 allowances and sold for just $31.12 in May’s second regular auction. An example from the APCR auction, with 32 bidders, illustrates the complexity: 8 entities that had been participating in regular auctions did not participate, while 5 entities that had not bid in the first two regular auctions took part in the APCR. These examples highlight why it is overly simplistic to attribute auction prices directly as consumer costs.

- The fossil fuel supply chain involves many steps, each with embedded profits. And it is well documented that the oil industry has been collecting record profits. The final retail sale is just one stage in the process of extraction, production, and delivery. Any point where profits are retained presents an opportunity for competition and differentiation. Assuming that consumers bear the full cost ignores other opportunities for differentiation or competition among entities that are prevented from sharing sensitive market information. Entities can explore compliance strategies beyond purchasing allowances. For example, “bp” invests $270 million in efficiency, emissions reduction, and renewable diesel production at the Cherry Point Refinery. Diverse and innovative approaches help meet emission reduction targets at a net cost lower than a direct carbon tax.

- A growing body of research suggests that carbon pricing in particular may not fully translate into consumer prices. Assumptions that carbon prices would be fully passed through are often based on experiences with more direct fuel taxes such as excise taxes. Some recent examples of real-world carbon pricing pass-through include:

- Shang 2023:

- “Kotchen (2021) finds an average pass-through of 0.85 for coal, natural gas, gasoline, and diesel, based on demand-and-supply elasticities.”

- Ganapati, Shapiro, and Walker (2020)

- “For the several industries we study, 70 percent of energy price-driven changes in input costs get passed through to consumers in the short to medium run. The share of the welfare cost that consumers bear is 25–75 percent smaller (and the share producers bear is larger) than models featuring complete pass-through and perfect competition would suggest.”

- Harju et al 2022:

- “We find that diesel carbon taxes are less than fully passed through to consumer prices on average: a one euro cent increase in the carbon tax leads to a 0.80 cent increase in prices. This result indicates that the economic burden of the diesel carbon tax is somewhat split between the demand and supply sides of the market, though consumers bear most of the burden. The finding differs from the related literature on fuel excise tax pass-through, most of which has documented full or nearly full pass-through.”

- Shang 2023:

A reliable comparison: Washington vs. Oregon

This brings us back to what we can derive about prices at the pump for a program that levies a compliance obligation upstream of the consumer and obligates compliance with tradable allowances primarily over four-year windows. We have been tracking real-world gasoline prices closely since the beginning of the program, and only one comparison stands out as reliable thus far: the relative increase in prices at the pump in Washington versus Oregon, as documented by AAA. The Seattle Times originally noted the consistency in gas prices between the two states, noting that “From 2015 and 2022, a gallon of regular gasoline in Washington was on average 11 cents more than in Oregon.”

This consistency makes sense, given the two states, especially the population centers west of the Cascades, are closely linked in supply and distribution with each other but not with other states in the region (see for example this West Coast Transportation Fuels Market report). This is why Oregon and Washington prices closely track each other but can see swings relative to neighboring states like Idaho or even other regional states in the closely monitored Petroleum Administration for Defense District (PADD) 5 such as California, Nevada, and Arizona.

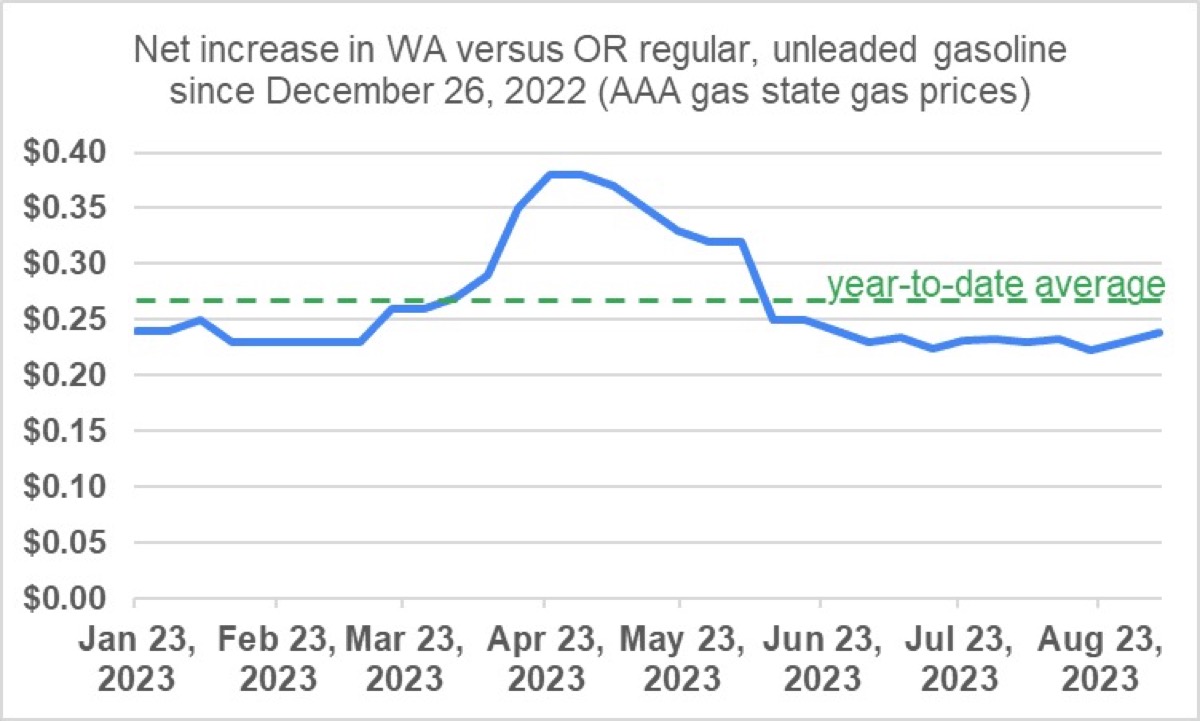

The spread of $0.11/gallon higher prices in Washington compared to Oregon noted by the Seattle Times aligns with the prices for regular unleaded gasoline at the most recent price minimum in late December 2022 ($3.74/gallon in Oregon and $3.85/gallon in Washington as of December 26, 2022). We can compare how much this spread has grown in 2023 as a relevant real-word measure of CCA impact at the pump. Washington relative prices jumped immediately to start 2023, increasing by a net of $0.24/gallon between December 26, 2022 and January 23, 2023. Since then, the relative price increase has stayed in a tight band, with a peak of $0.38/gallon in late April before settling at $0.22 to $0.25/gallon since June 12th. The year-to-date average (January 23-September 5) has been an increase of 26.7 cents per gallon more in Washington than in Oregon according to AAA data (see chart below). For a less efficient than average (20 mpg) vehicle with above average usage (15,000 miles per year), this translates to about $0.50/day in added fuel costs.

Source: AAA data, combining Clean and Prosperous Institute and Yoram Bauman data collection and analysis

Compared to a simple pass-through assumption on allowance prices (non-consigned average $53.32 through August’s APCR auction, translating to 42 cents per gallon of gasoline), the WA vs. OR year-to-date average of 27 cents per gallon indicates around 70% pass-through. This level of pass-through is consistent with the range described in the peer-reviewed literature.

We will continue to closely monitor this as we await a full-year and a full compliance period of allowance sales, and monitor secondary market transactions. However, we believe this is the metric that reveals the most about the CCA’s average impact at the pump.

Less useful comparisons – the broader West Coast region

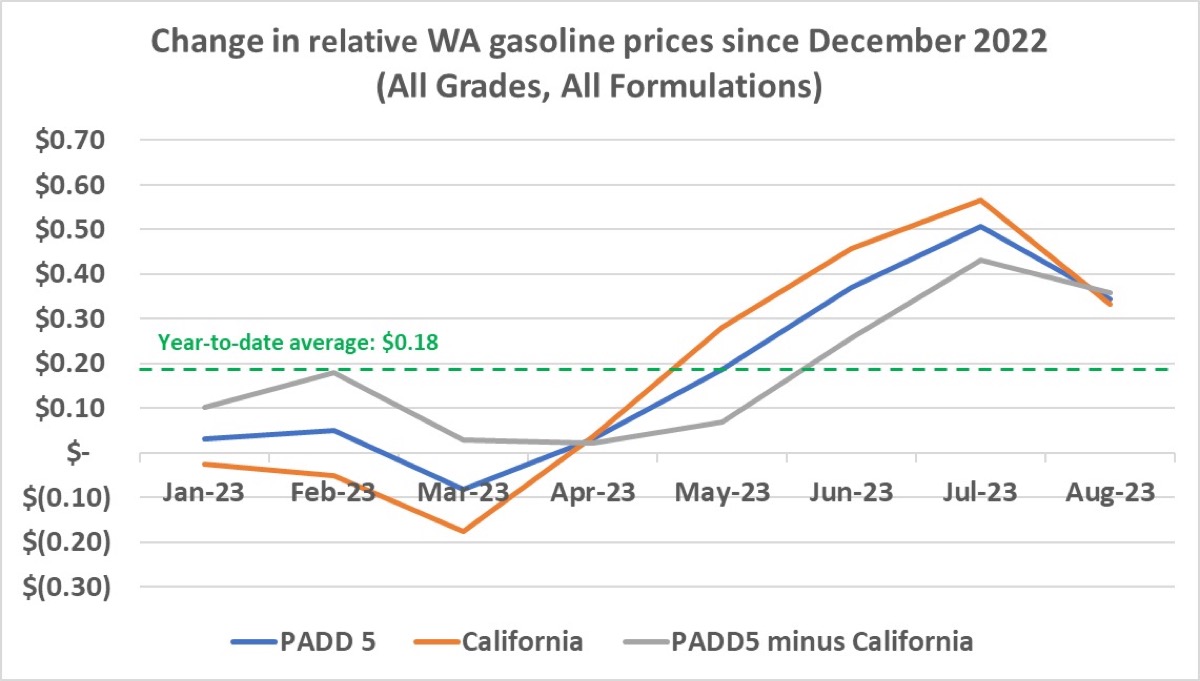

While it’s important to evaluate all the available comparisons, not all are equally reliable. There have been some attempts by others to elevate a comparison of Washington net increases at the pump relative to a wider range of neighboring states. The US Energy Information Administration tracks Washington, California, and regional (PADD 5, and PADD 5 minus CA) average fuel prices. The comparison of Washington gasoline price increases relative to the full PADD 5 is the likeliest source of summertime claims that the CCA has impacted gasoline prices by 50 cents, an amount greater than full pass-through. Looking at a full year of data (see chart below), we share three main observations:

Source: Clean and Prosperous Institute analysis using EIA weekly price data (https://www.eia.gov/petroleum/gasdiesel/)

- There is no consistent correlation between the CCA – either start dates or auction dates – and the price gap between the regions.

- The gap peaked at the beginning of summer after a long period of low (and even negative) increases. Focusing on peaks (or valleys), especially when sampled from volatile and weakly correlated comparisons, is not a good approach to isolating the program impacts.

- Year-to-date average differences, though not closely correlated to program start or auctions dates unlike Oregon, are much less than 50 cents. The year-to-date average is $0.18 cents per gallon increase whether comparing to California, the full PADD 5 region, or the PADD 5 region minus California (Alaska, Arizona, Hawaii, Oregon, Nevada). That is the full-set of comparisons in the PADD 5 region available with EIA data.

The $0.50/gallon claims that have been made coincided with the maximum spread in July 2023. Attributing the overall program impact to the highest number observed in 7 months is not a reliable measure. The overall volatility throughout the year and lack of correlation with the program indicates that other metrics are needed to capture the impact of the CCA on prices at the pump. Washington and Oregon prices are the most consistent observed since the start of the program, a correlation that extends back in time.