This story originally was published on Gas Outlook and is the second of a two-part long read on LNG expansion in Louisiana and its impacts on the local community. Read the first part here.

(Cameron, Louisiana) — John Allaire spreads an old map across his table, which shows what his property in Cameron, Louisiana looked like in 1982.

“This used to be all solid trees, trees, trees,” he said. “But four hurricanes since 2005 and sea level rise — it really decimated this coastline.” He estimates that 70 metres of his property has been swallowed up by sea level rise since he moved there in 1998, with trees and wetlands washed away as the ocean advanced bit by bit with each passing year.

“Rita was really, really bad,” he said, referring to the 2005 hurricane that decimated Cameron Parish. “I had a house right over here. The only thing that I found were the bricks that it was set on.” The power lines had been replaced four times in the past two decades.

“It was like God wiped a squeegee over the place,” he said.

Allaire spent more than three decades as an environmental engineer in the oil industry, working for Amoco and then BP, after the two companies merged in the late 1990s. He now lives in an RV parked on a slightly elevated ridge called a chenier, surrounded by grassy wetlands and mudflats. The chenier is about five feet about sea level and it used to be covered in oak trees.

The trees are no longer there. They were ripped up, snapped in half, and blasted away by Rita’s storm surge that topped 15 feet. “This was completely wooded before,” Allaire said, pointing to grass and shrubs. Still, the cheniers and the surrounding wetlands provide critical habitat for fish, shrimp, ducks, and an array of migratory birds travelling across the Gulf of Mexico. They also provide a buffer against floods and storms.

But the coastline is under threat from more than just climate change. Entire sections of wetlands are being filled in and paved over to build LNG export terminals, which will ship fracked gas to Europe and Asia. Those facilities will, in turn, exacerbate the climate crisis that is ravaging the Louisiana coastline where Allaire lives.

However, the LNG buildout is now in limbo. While several LNG terminals currently under construction will continue, the Biden administration in January put a halt to new applications while the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) revises its review process.

At issue is one big question: Is exporting gas in the “public interest”? DOE said it would look more carefully at the effects of ever-increasing volumes of gas overseas, scrutinising the impacts on the climate, the economy, and local communities such as those in southwest Louisiana, which is ground zero for the LNG building boom.

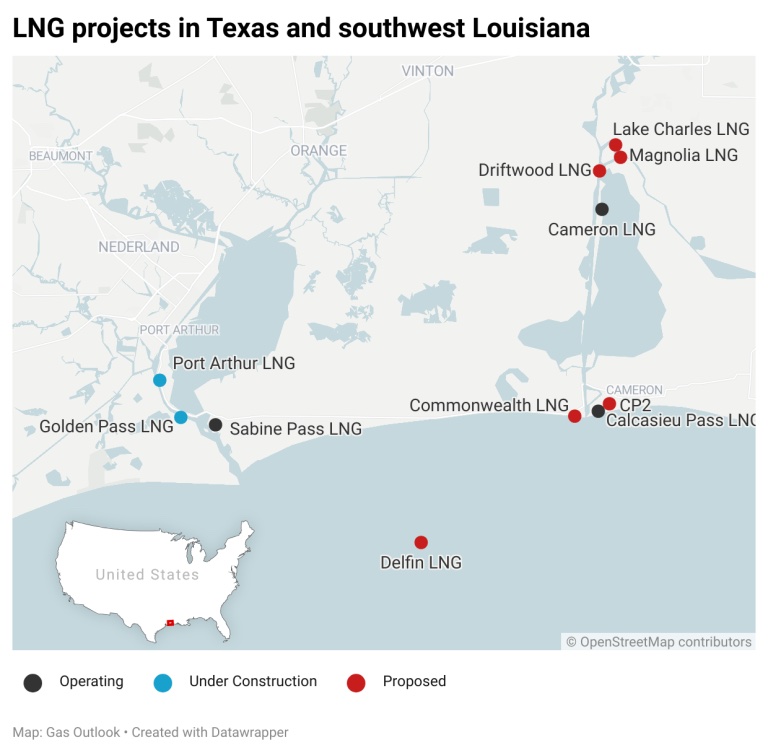

For some residents, the answer is clear. “We have enough of this shit,” said James Hiatt from For a Better Bayou, a Louisiana-based NGO. “I mean we got three of them here in southwest Louisiana. And another one, Golden Pass, has another year or so before it’s finished.”

Those are just the existing LNG terminals. Roughly six more LNG projects are slated to be built in southwest Louisiana, if developers can secure permits and financing.

“This idea that we can just keep building these…I mean, what are we doing?” Hiatt said.

America’s Gas Export Boom

In order for an LNG project to constructed, it needs to obtain authorisation from the Department of Energy to export to countries that don’t have a free-trade agreement with the U.S. (exporting gas to countries that do have a free-trade agreement with the U.S. is automatically considered to be in the public interest).

For the past decade, that has been largely a check-the-box exercise — DOE has never rejected an application.

But that process is now set to get a major overhaul. DOE announced in January that it was pausing approvals on new LNG projects while it reassesses the criteria it uses to evaluate applications.

The oil and gas industry was immediately outraged that the Biden administration decided to pause new LNG approvals. “This is a win for Russia and a loss for American allies, U.S. jobs and global climate progress,” the American Petroleum Institute (API) CEO Mike Sommers said in a statement.

DOE points to a 2018 economic study to justify its approval of every application that comes its way.

That study, now six years out of date, is “ancient history,” Tyson Slocum, director of the energy programme at Public Citizen, a Washington DC-based consumer advocacy organisation, told Gas Outlook.

Since 2016, when the first American LNG cargo was exported, the U.S. has gone from exporting no LNG at all to becoming the largest exporter of LNG in the world, shipping out 88 million metric tonnes 2023.

As a result, a growing portion of domestic production is being diverted for export. In 2022, the U.S. exported about 10 percent of its supply. That figure has since climbed to 13 percent, and will jump sharply when the next wave of LNG terminals comes online beginning in 2025. By 2028, around 20 percent of U.S. gas production will be earmarked for export. If every project that is on the drawing board actually gets built — to be sure, an unlikely scenario — the U.S. would be exporting half of its total current gas production.

The commercial logic of U.S. LNG rests on the fact that cheap American gas can be sent overseas where prices are much higher. But with such large amounts of gas now shipped abroad, gas markets in the U.S. have become increasingly intertwined and inextricably linked to markets in Europe and Asia. The effect is for the prices in various markets to converge, essentially dragging up U.S. gas prices closer to those other, costlier regions.

“There’s no question that the introduction of this kind of volume of LNG exports is having an upward pressure on prices,” Slocum said. “It has globalized formally segregated U.S. benchmark prices. There’s no one that can deny that simple fact.”

“U.S. is exporting natural gas, and importing price volatility.”

Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis

DOE acknowledged that the world has changed dramatically since its last review. “Since 2018, there have been truly transformative changes that need to be fully incorporated in our analysis,” David Turk, deputy secretary at DOE, told a Senate panel during a Feb. 8th hearing. “The United States has already tripled our export capacity in just five years, becoming the world’s largest LNG exporter; our capacity may nearly double again by 2030; and total exports already authorized would nearly double that total again.”

In 2022, American consumers spent $269 billion on natural gas supplies, up sharply from $150 billion in 2019, according to the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis (IEEFA). While Russia’s war in Ukraine was the initial spark that caused the energy crunch in 2022, American gas prices increased sharply in tandem with global prices because they are now heavily linked. IEEFA said that “there’s absolutely no doubt that surging LNG exports helped trigger the surge in U.S. gas prices,” adding that “the more export capacity we have, the more likely it is that a gas supply disruption anywhere in the world will trigger a price spike here at home.”

Or, as IEEFA has summed it up previously, the “U.S. is exporting natural gas, and importing price volatility.”

More recently, domestic prices have crashed, in part because of warm weather and high production. But the fact remains, linking domestic U.S. gas markets to global markets leaves the U.S. vulnerable to the next global price spike.

The influence of LNG exports is clearly visible when unexpected supply shocks occur. For instance, when Freeport LNG suffered an explosion in June 2022, knocking a chunk of export capacity offline for an extended period of time, U.S. natural gas prices immediately plunged by 17 percent, as market traders understood that more gas would be trapped at home.

On Jan. 29th, 2024, U.S. natural gas prices sank by 8 percent, in part because of news that a unit at Freeport LNG was once again forced offline after complications from a winter storm.

Opponents of LNG exports can make for some odd bedfellows. The Industrial Energy Consumers of America (IECA), a trade association of more than 12,000 manufacturers across the country, joined with environmental groups in calling for a federal pause on approvals of new export terminals, citing the impact on gas prices. Many of the IECA’s members use natural gas in their manufacturing, and thus, want gas to be cheap and plentiful.

“As LNG exports increase, so do reliability and price risks for the natural gas and electricity markets,” the IECA wrote in a January letter to the U.S. Department of Energy, warning that “a lot of things can go wrong” that can lead to supply disruptions.

A recent study by Energy Innovation LLC, a San Francisco-based think tank, found that if all the pending LNG export terminals were completed, it could result in an increase in U.S. natural gas prices by 9 to 14 percent. The negative impacts could decrease over time if gas producers responded by increasing drilling.

DOE has now promised to take all of this into account in its pending review. The 2018 analysis that the agency uses to justify exports concluded that American consumers would benefit from gas exports because they may own stocks in energy companies, which would outweigh the downside from higher prices. Unfortunately, many people do not have enough wealth to own any stock at all, and low-income households are the most likely to bear the brunt of costlier energy. In its recent decision, DOE suggested reevaluating its criteria to look more closely at who wins and who loses, and not just at high-level GDP impacts.

The oil and gas industry, and many Republicans in Congress, demanded the Biden administration immediately lift the pause, and some even threatened legal action. But unlike the market for oil exports, which has very little regulation, gas exports are different. The federal government has legal tools at its disposal to protect American consumers from price volatility, and can halt LNG exports or put stipulations on export volumes, if needed.

“We’ve got a pretty sweeping statutory consumer protection on the books,” Slocum said. “All we’re asking is for the Department of energy to enforce it, reasonably.”

Stricter Climate Scrutiny

The U.S. government’s continued approval of LNG export terminals was also based on the assumption that gas would displace coal overseas, providing incremental greenhouse gas reductions.

That premise has begun to fall apart as research on methane has piled up in recent years, examinations that consistently point to an industry-wide problem that is much worse and much more widespread than previously thought. For instance, research shows that upstream methane leaks in the Permian basin — the region supplying gas to many Gulf Coast LNG terminals — are several times higher than federal government estimates. It doesn’t end there. As Gas Outlook reported last year, the LNG terminals themselves are leaking methane that is going unrecorded.

Most notably, new research currently under peer-review from Robert Howarth at Cornell University, finds that not only does methane leakage occur at every stage of the gas supply chain, but an under-appreciated source of planet-warming methane comes during transit. Some LNG evaporates while on board and on older tankers, and it must be vented into the atmosphere as unburned methane to avoid a buildup in pressure.

Taken altogether, Howarth concludes that emissions from LNG are 24 percent worse than coal — and that’s in a best-case scenario. In a worst-case, LNG could be twice as bad for the climate than coal. Howarth concluded that “ending the use of LNG should be a global priority.”

LNG proponents argue that Howarth’s research is an outlier. And industry-backed research shows significant climate benefits of exporting LNG, if it is used to replace coal. On top of that, corporate pledges to reduce methane leaks over time would also improve the emissions profile of LNG.

But even if LNG, in some cases, could knock coal offline in China, for example, experts still say it is not a climate solution. “If you’re even in the ballpark of coal, then we’ve got problems,” Jeremy Symons, an energy and environmental analyst, told Gas Outlook. Symons published a report last year that found that if all U.S. LNG projects that are on the drawing board actually get built, then it would result in 3.9 gigatons of greenhouse gas emissions, larger than the total GHG emissions from all of the European Union.

Ultimately, climate experts overwhelmingly conclude that fossil fuel infrastructure needs to be phased out — and governments agreed to that goal at COP28 in Dubai late last year.

Yet the LNG expansion goes in the opposite direction. LNG projects under construction on the Gulf Coast, which will come online in the late 2020s, will expect to operate through mid-century, locking in decades of climate pollution.

“You can’t transition away from fossil fuels while building out massive new infrastructure designed to deliver new fossil fuels for decades to come,” Symons said.

But he added that the DOE pause on new approvals could be a turning point. “The reason the oil and gas lobby is panicking, and that frontline communities and climate action advocates are celebrating, is because both sides know the same thing — that these projects will not stand up to any kind of serious scrutiny of the facts.”

Ravaged by Hurricanes

There is arguably not a more dramatic side-by-side exhibit of the climate crisis and America’s fossil fuel boom, both unfolding at the same time, than in Cameron Parish, Louisiana, where LNG terminals are springing up like mushrooms in marshlands that are becoming increasingly unliveable.

Southwest Louisiana is no stranger to hurricanes. Cameron was hit by Hurricane Audrey in 1957, one of the deadliest in the nation’s history, which killed over 500 people. But the region then had about 50 years of relative calm. That is, until Hurricane Rita in 2005, which delivered a devastating blow that the region still has not entirely recovered from, and probably never will. The entire community of Holly Beach was wiped out. Then another storm washed through in 2008. And in 2020, the region was hit again, this time by a one-two punch from back-to-back hurricanes.

Signs of decline in Cameron are ubiquitous. Rusted shrimp boats washed in from past storms sit abandoned in the grassy marsh, tilted on their sides. Twisted metal from a fish processing plant sits in a pile by the river. Even a facility that once serviced offshore oil platforms has been left to the elements, half of its wall sheared off.

Today, some of the houses in Cameron have been rebuilt, but many have not. The skeletons of damaged buildings with roofs ripped off from high-speed winds dot the landscape — churches, homes, stores — some with chain-link fence around them, others covered with tarp or plywood. Trash and years-old hurricane debris are still visible through the tall grass on the side of the road. Most of the public libraries were closed years ago because of storm damage. Rather than repaired, they remain shuttered.

Rebuilding is technically possible, and some pricey beach homes and vacation rentals have since been constructed at the beach. But there are stricter building codes that require homes to be built on elevated stilts. While a sensible policy to avoid future catastrophic losses, the costs of building hurricane-proof homes can be prohibitive. Obtaining flood insurance is also difficult and expensive.

Instead, some people have returned to Cameron and live in RVs and trailers, which can be hauled away when the next hurricane hits. But others never came back. On the eve of Hurricane Rita in 2005, Cameron Parish had a population of around 10,000 people. That has since declined by more than half to less than 5,000.

Cameron was once home to a thriving commercial fishing industry. A few decades ago, it was the largest producer of seafood in the country. Nowadays, fishermen and shrimpers are an endangered species, and the LNG buildout threatens to put them out of business for good.

It seems that LNG developers and the local Parish government are trying to “depopulate” the area, Lori Cooke, an organiser with the Louisiana Bucket Brigade, told Gas Outlook. Cooke’s grandfather worked for Shell Oil and she had other friends and family in the oil and gas industry. “There used to be a proud tradition of plant workers” in southwest Louisiana, she said. But that is no longer the case.

“Cameron would get periodic storms, but there was a culture of rebuilding and fighting back,” she said. “The difference now is there are so many LNG plants.”

Allaire said the same thing. “They don’t want people down here. They closed off all the public fishing areas. They closed off the Jetty Park over there,” Allaire said, referring to a once popular park where people would gather for festivals. “Unless you’re LNG, they don’t want you down here.”

He has spent the past two years documenting the chronic air pollution events, permit violations, and operational mishaps at Venture Global’s Calcasieu Pass LNG, as Gas Outlook has previously reported. For instance, in the first 90 days of operation, Venture Global’s facility flared gas on 84 days, despite telling regulators beforehand that flaring gas would be a rare occurrence.

Those problems may have gone unreported — or, at least, not widely known — if not for Allaire, who has been something of a lone sentry, living in a sparsely populated part of the Louisiana marsh, monitoring the massive LNG buildout occurring in southwest Louisiana.

Even as he’s living in the shadow of America’s gas export boom, he’s also on the frontlines of the climate crisis. The sea is devouring his coastline and his home was washed away in a hurricane. Last year, his RV was encircled by a raging wildfire, a terrifying development in an area unaccustomed to drought. “I never saw a drought like that, ever,” Allaire said.

The LNG companies themselves are preparing for more climate disasters. Commonwealth LNG, which would be built next to John Allaire’s property, is planning on filling in the wetlands with millions of cubic feet of dirt to elevate the ground, and then building a 26-foot metal wall around its facility. A 300-foot gas flare stack would sit just a few hundred feet from his RV, yet another giant torch burning gas and lighting up the night sky near his home.

Commonwealth LNG is now ensnared in the DOE pause initiated by the Biden administration, and will likely be delayed by a year or so. But if that project goes forward, the massive metal wall the company would erect, making the facility a fortress, may deflect rising sea level and storm surge towards Allaire’s property, significantly increasing the danger to him.

“If you back fill this whole area, you destroy the drainage,” Allaire said, referring to Commonwealth’s plans. “All this will flood,” he said, referring to the wetlands on his property. “I mean there’d be no way for the water to get out.”

Commonwealth LNG did not respond to questions from Gas Outlook.

When asked if he could continue living in Cameron if Commonwealth goes forward, he said: “Well, I’m gonna try. They’re gonna be forced either to buy me out or not operate the plant. I’m not going anywhere.”

Subscribe to our newsletter

Stay up to date with DeSmog news and alerts