David Slutzky, an accomplished entrepreneur, has an eclectic background. In addition to having founded several successful companies, he’s served as a local elected official as well as a Senior Policy Advisor in the Clinton White House and the EPA. He’s been teaching at the University of Virginia for some time, on the Commerce, Architecture and Engineering faculties.

Slutzky founded vehicle-to-grid pioneer Fermata Energy in November, 2010. Other members of the Fermata team include Tony Posawatz, a former GM exec who was responsible for bringing the Chevrolet Volt to production, and later served as CEO of Fisker Automotive; and David Sandalow, an energy policy expert who held senior positions at the White House, State Department and DOE.

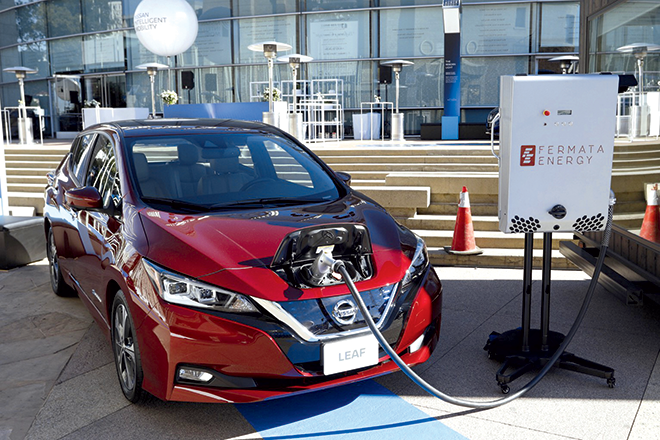

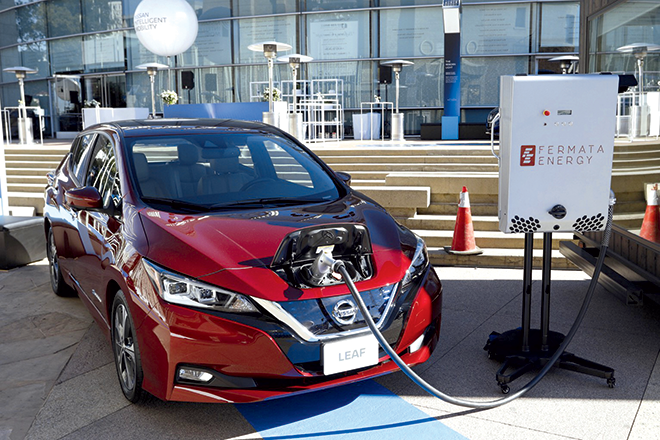

Fermata has been in the news lately for a couple of reasons. In November 2018, the company partnered with Nissan to launch a pilot program that uses LEAFs equipped with bidirectional charging capability to partially power the automaker’s North American headquarters in Tennessee and its design center in San Diego. In January, Fermata scored a $2.5-million investment from TEPCO Ventures, the investment arm of Tokyo Electric Power. In July, Nissan’s announcement that it was using vehicle-to-home (V2H) technology in Japan, and would soon offer it to customers in Australia, brought more attention to Fermata (although the company isn’t directly involved in either of these initiatives).

V2Everything

The term vehicle-to-grid (V2G) refers to the concept of using vehicle batteries to provide services to the electrical grid, whereas the related concepts of vehicle-to-home (V2H) and vehicle-to-building (V2B) are about using the batteries for more local applications, such as storing solar energy and releasing it at night; smoothing out consumption to avoid utility demand charges; or providing a backup in case of power outages. Some use yet another acronym, V2X, which includes all the various variations of the concept. For simplicity’s sake, we’ll mostly stick with the term V2G in this article.

The missing link

“I founded Fermata Energy for two specific reasons,” Slutzky told Charged. “I wanted to accelerate the adoption trajectory for electric vehicles, and to accelerate the transition to renewables on the grid. I quickly figured out that those two are intertwined in a beautiful way.”

“The real obstacle to adoption of EVs at this point is that they’re more expensive,” says Slutzky. “But cars are parked most of the time. If they could earn money while they’re parked such that the total cost of ownership of an EV were to become less than that of an ICE vehicle, that [would get] interesting really fast. So how could EVs make money while they’re parked?”

In an interesting bit of serendipity, the answer to this question could also answer another question: What’s the biggest obstacle to the adoption of renewables on the grid? “It’s not the cost of generating the electron,” says Slutzky. “Creating an electron with wind and solar is clearly cheaper than nuclear, and certainly cheaper than coal at this point. It’s the absence of energy storage on the grid that prevents scaling of renewables.”

Some years ago, Slutzky read an article that said that if you electrified a quarter of the vehicles on the roads of America, you would have energy storage roughly equal to the entire output of the US power grid in those batteries. That’s when the light went on, so to speak. He saw that vehicle-to-grid technology could be a focal point that enabled EVs and renewable energy to complement each other. “I founded Fermata Energy specifically to enable electric vehicles to earn money while they’re parked by providing energy storage to the grid.”

The threefold path

To make this symbiotic relationship work, three components are required. “You need a bidirectionally enabled vehicle, you need a bidirectional charging capability, and you need software to facilitate the interplay among the vehicle, the charger and the revenue-generating opportunities,” says Slutzky. “There really weren’t any bidirectional vehicles when I started the company, there weren’t any bidirectional chargers, and the software needed to be written. We were starting from scratch to put those three things together. So we spent a few years trying to develop a relationship with somebody who would make a bidirectional vehicle.”

Slutzky’s initial plan was to work with Gordon Murray, the famous designer of Formula One racing cars and the McLaren F1 supercar. “We worked with Gordon and some other people for a couple of years to try to get somebody to build a replacement vehicle for the US Postal Service – those long-life vehicles that are way past their useful life – and replace them with a bidirectional electric vehicle. That was our first strategy. When we discovered that the Nissan LEAF had become bidirectional in 2013, we kind of pivoted as a company. We’re ultimately vehicle-agnostic, and are working with other OEMs, who will eventually bring bidirectionally enabled vehicles to the US market, but for now, happily, there’s the LEAF – Nissan really does get it.”

The LEAF provides the first piece of the puzzle – the second piece is the bidirectional charger. “It has to be off-board,” says Slutzky. There were none available when Fermata began its quest, so the company built its own. However, it is now working with several charger manufacturers. “Hopefully they’ll make them better, cheaper and faster than ours, but they don’t necessarily know how to make money off of them, that’s not what their business is. Ultimately we’re charger-agnostic in much the same way we’re vehicle-agnostic.”

“The third thing we needed was software, and in order to get that, we ended up acquiring a team that had in a previous life developed the software backbone for Duke Energy’s microgrid program,” says Slutzky. “That team is particularly strong at having different types of power electronics equipment talk to each other and operate seamlessly, which is what we felt we needed. So we’ve acquired that team, and that will always be in-house.”

Fermata now has the three pieces of the puzzle in place – the next challenge will be bringing them together to produce income. “Our real strength as a company is having spent seven years studying how you make money with this technology,” Slutzky explains. “That’s really our secret sauce, since we understand pretty deeply what we call the monetization pathways for vehicle-to-grid.”

“I was at the Roadmap 12 conference out in Portland last month and we talked with board members from the California Energy Commission, and the California Air Resources Board, and when we showed them a live demonstration of what we’re doing, they were like, ‘Wow, we had our own studies that said you can make hundreds of dollars a year, and you’re showing that you can make thousands of dollars a year, and that you’re actually about to be commercial and doing it.’”

“So I think a lot of people just don’t realize how far vehicle-to-grid has come. It’s about to become a significant scalable opportunity. I’d like to believe that Fermata Energy’s at the front of that, although there are other V2G companies that are trying to do the same thing, different versions.”

What’s the frequency?

There are different types of customers that an EV can provide value to – one possibility is providing frequency regulation services to grid operators. Fermata is with a member of PJM Interconnection, a regional transmission organization that serves some 14 states in the Mid-Atlantic region. “PJM has a mature market where you could provide frequency regulation services and be compensated for them,” says Slutzky. “Fermata is a curtailment services provider for PJM, and we can take a bunch of electric vehicle assets and aggregate them and earn money by responding to a signal from the grid.”

“The problem is, it’s not a great market, it’s poorly structured, and it’s heavily correlated to the price of natural gas, which has been going down over the years. So you can make maybe 1,000-1,500 bucks a year with a LEAF doing frequency regulation.”

If you want something done right…

In 2016, Fermata bought four chargers and began a demonstration V2G project in Danville, Virginia. “They were 30 kW bidirectional chargers that weren’t fully certified, and they weren’t really a scalable product at the time,” says Slutzky. “So we learned how to do frequency regulation, but we figured out pretty quickly that there really wasn’t a good charger solution [available].”

“We looked at every charger manufacturer across the globe, and we found this small company in Blacksburg, Virginia, a spinoff from Virginia Tech, which had developed a design for a bidirectional DC fast charger using silicon carbide. It was really state-of-the-art – most of these bigger car chargers are the size of a refrigerator, and the bottom half of that refrigerator is the transformer. These guys had developed a charger with a transformer that was about the size of a Kleenex box – very interesting leading-edge technology. So we entered into a contract with them to develop a charger for us. Then a little while later we just acquired them, because it was a good match.”

“So, through our charger subsidiary, we’ve been developing a bidirectional DC fast charger for the US market,” Slutzky continues. “A 15 kW version of it is going to be fully UL-approved and certified and on the market late this year. Very quickly on the heels of that will be our 25 kW version, which is mostly done now. We just wanted to get something through UL as quickly as we could. UL’s tricky – we’re learning how to do certifications for a bidirectional charger in the US, we’re doing a lot of things that nobody’s done before, and we wanted to make sure we knew what we were doing.”

Shaving and saving

Fermata has several of its chargers running at demonstration sites. One of these is being used for behind-the-meter demand charge management – an entirely different application than frequency regulation. “Just last month, on a really hot day, we shaved $183 off the customer’s electric bill in about 15 minutes,” says Slutzky. “And we can do the same thing at other customers’ sites very effectively. If this were a California location, and it had the 25 kW charger, it would have been able to earn about $9,000 a year doing what it was doing.”

This particular installation is doing localized peak shaving for a small facility, but such a system can also do utility-level peak shaving. “We can participate in critical peaking events. There are a series of what we call monetization pathways that we’ve developed over the years for this technology that we know how to do well. We’re doing some of them at this demonstration site in Danville, but just doing behind-the-meter demand charge management we can make some pretty good money. So that’s what Fermata is focused on.”

Getting the word out

Fermata has figured out how to do behind-the-meter demand charge management effectively, but Slutzky says, “It’s ultimately the utilities that are going to be where the value is. The real value of vehicle-to-grid is going to be providing a number of services to utilities and the grid.”

Word of what Fermata has to offer is starting to spread. “We initially thought that we would have to get a sizeable number of EVs aggregated into a single system, and be able to demonstrate that we could provide a couple of megawatts of power, to even begin a conversation with the utilities,” says Slutzky. “But as soon as the Nissan announcement happened at the end of November, and then the announcement that TEPCO had invested in Fermata to bring this technology to Japan, we quickly got calls from utilities all over the country. We’re now working with a dozen or so US utilities to do vehicle-to-grid work. Those are going to be among our early deployments to work through different cases to figure out how this can work for them. They know that there’s value here, and together we’re figuring out how to make that work financially.”

“After our first deployments in late 2019 and early 2020, we’re going to operate aggressively in the workplace-charging space. And then it isn’t a big step from there to go to the end of the cul-de-sac with individual consumers. You need to reach a critical mass of EVs in your network to be able to meaningfully serve non-commercial customers. We will be able to do that within a couple of years.”

Fermata aspires to be “the Android of vehicle-to-grid. We want to be the guys that figure out how to make money, put all the vehicles together, offer them to the different grid-facing customers, then create a big monetary pie and share it with the customer and with all the stakeholders.”

Will V2G hurt your battery?

When Charged has covered V2G tech in the past, we’ve gotten reader comments along these lines: “I own a LEAF [or a Tesla] and I’m scared to death of losing battery capacity as it is, so no thanks!” It’s a valid concern – will using V2G tech affect battery life?

It depends, Slutzky tells us. “There are some uses of a battery that could have degradation impacts, and there are other uses that have less impact. There’s even a study that was done in the UK that looked at behind-the-meter demand charge management and frequency regulation, and they conjectured that under some circumstances you could even extend the life of the battery.”

Savvy EV owners know that topping up a vehicle to a 100% state of charge can adversely affect battery life. Some EVs’ onboard charging systems make it easy to charge to, say, 90%, and others don’t. A V2G system, however, could keep every vehicle on the network at an optimal state of charge.

“If you’re part of a managed system of vehicle-to-grid operation, that operator is going to keep your battery below 100% state of charge, except when you let the operator know that you’re going to want to drive it,” says Slutzky. “Over time people will learn that [in regards to] vehicle-to-grid activities, the ones that are harder on the battery, we won’t do anything that doesn’t earn 10 times the value of any potential battery degradation. And most of what we do doesn’t degrade the battery in a meaningful way at all.”

A V2G scenario

What will Fermata’s system look like in the real world? “Typically the customer will own the vehicle, we will provide the use of a Fermata charger, and then we’ll operate the charger in a fashion that coordinates with the customer,” says Slutzky. “We have a very important guiding principle – we know that a customer buys an EV so that they can drive it. We don’t want to tell them, ‘You can’t drive it because we’re going to use it to make money,’ or ‘You can’t drive it because we’ve drained your battery. Sorry.’ We’re very careful to work with the vehicle operator so that we let them know [for example] ‘You could make this much money at two o’clock on Thursday or you could drive it. It’s up to you.’ We will operate the vehicle-to-grid activity in conjunction with the duty cycle requirements determined by the customer.”

There are several different value propositions that could be appropriate for different customers. “The customer could participate in the frequency regulation market and get a check for doing that, or if they are at a workplace they might get paid by their employer to help the employer reduce their building load peaks, or they might get some money for helping a utility reduce its peaks. All of those are revenue-generating pathways that we’re experts in and we can monetize. But there are others.”

“For example, backup power is something that’s been actively developed in Japan. Nissan was doing that years ago and TEPCO is fascinated by that [application]. They invested in us to bring this technology to Japan. A residential customer could get paid by making their vehicle available while they’re not driving it. Over time we’ll be able to add more and more revenue opportunities to this business. I don’t know how much value an individual customer’s going to be able to capture, but it’s all better than a current EV, because the current EV can’t make a dime. And an internal combustion engine vehicle never, ever will. It’ll always be a cost center.”

This article appeared in Charged Issue 45 – September/October 2019 – Subscribe now.