How can the world kick its oil habit?

A lengthy overview of our addiction to oil, and the methadone we need in order to kick the habit

Summary - The world runs on oil, whether we like it or not. How then, do we transition from fossil-based oil towards a sustainable future? This blog reveals why we are addicted, and provides the two forms of methadone needed to transform the transportation, buildings and industry sector. Be prepared to wonder, be surprised, laugh and cry a little as we explore this question using pre-corona predictions. Don’t agree on the assessment or the different pathways to get rid of fossil fuels? Comment down below.

This blog is a review of an article from the Financial Times, which first appeared in February 2020. It was only weeks before the fossil fuel industry started its worst year ever. The article has been amended and commented upon by Mr. Sustainability (in italic), with the knowledge of the events of the latter part of 2020 and 2021.

“Can the world kick its oil habit?”

A rhetorical question surely

During the last weeks of the first lockdown in 2020 - when lockdowns were still special - I stumbled upon an article in the Financial Times that made me blink in disbelief. The article was called ‘can the world kick its oil habit?’. I saw it, I read it, I was triggered.

I was triggered due to the - in my view - silly nature of the question. Just days before, I wrote an article on the future of fossil fuels when oil prices were actually negative for the first time in human history. Clearly the future of oil and its industry was in doubt by everyone, including people working in the oil and gas industry - like me. However, the Financial Times article was incredible bullish on its future. Why?

Because it was published only weeks before the pandemic hit. In an instant, Corona turned the entire future of the oil and gas industry upside down. It became clear to everyone that things can change. We can kick our oil habit. And we will. The only question that remains is how will we do this? How can the world kick its oil habit?

I will show you the way to recovery. I cannot promise you it will be quick and easy, but there lie great rewards at the end: jobs, investment opportunities, technological challenges and of course the end of climate chaos.

Follow me on this journey, as we get an overview of our addiction, examine the reasons why we like it so much, and explore different solutions - the methadone needed - for the transportation, buildings and industry sector.

“The problem is absolutely immense. But humanity is capable of spectacular achievements.”

The world and its oil addiction

An overview of global oil consumption

The world runs on oil (1).

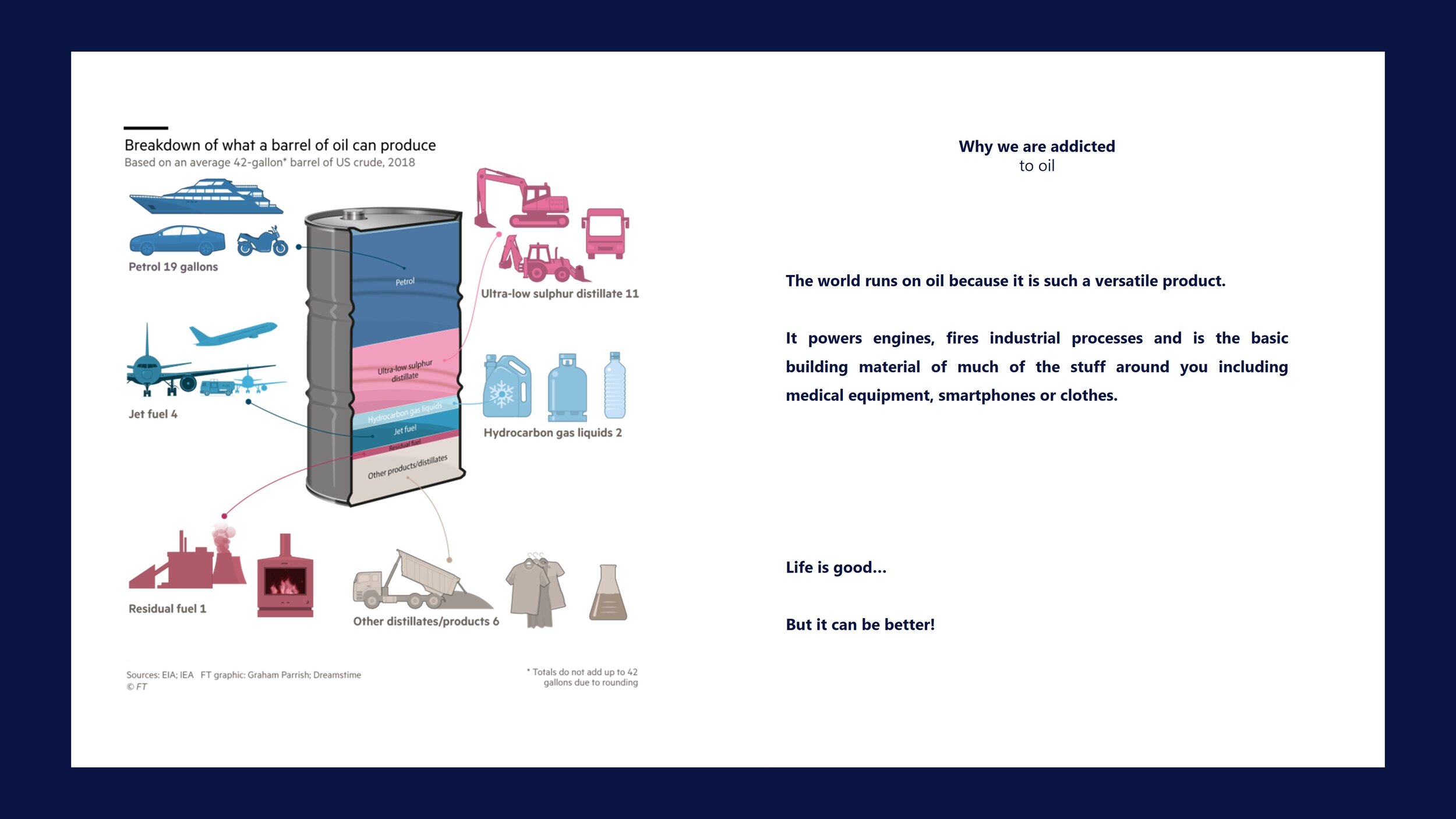

The dark, often viscous liquid is the single biggest contributor to the world’s energy mix, at 34 per cent of consumption, followed by coal at 27 per cent and natural gas at 24 per cent. But the fossil fuel has also quietly seeped into other aspects of our lives: from paint, washing detergents and nail polish to plastic packaging, medical equipment, mattress foams, clothing and coatings for television screens.

In 2019, global demand reached a record 100 million barrels a day, driven in part by the needs of rapidly industrialising emerging markets. This is why Sultan Al Jaber, head of the Abu Dhabi National Oil Company (Adnoc), is spending $45bn to expand the country’s refining and petrochemical capabilities (2).

“We are doubling our refining capacity,” Jaber told foreign oil executives and reporters at the company’s headquarters last year. “No one in the region or in the industry at large is undertaking such a massive expansion.” Even as our thirst for oil seems insatiable, it is becoming politically and environmentally toxic.

As the world wakes up to the catastrophic impact of climate change, from rising sea levels and drought to wildfires and crop failure, scientists have warned of a need to rapidly shift away from fossil fuels. Yet when it comes to oil demand, there is little sign of this happening (3).

Our usage has jumped 62 per cent over the course of a few decades — up from 61.6 million b/d in 1986. The International Energy Agency (IEA) forecasts that if governments continue with current policies, global demand will reach 121 million b/d by 2040. How the world can provide abundant energy supplies while dramatically reducing emissions has become one of the defining issues of our time.

These predictions have turned out to be far from accurate. In fact, the opposite was proven to be true. If we compare the projections made by the Financial Times just weeks before the pandemic, and those made by BP only a year after, we can see a paradigm shift. In all likelihood, 2019 marked peak-oil and we will never use as much oil as we did then. Fortunately, this would put us on track on the sustainable development scenario, though we should not count our blessings yet. We are still addicted, and there are very clear reasons why.

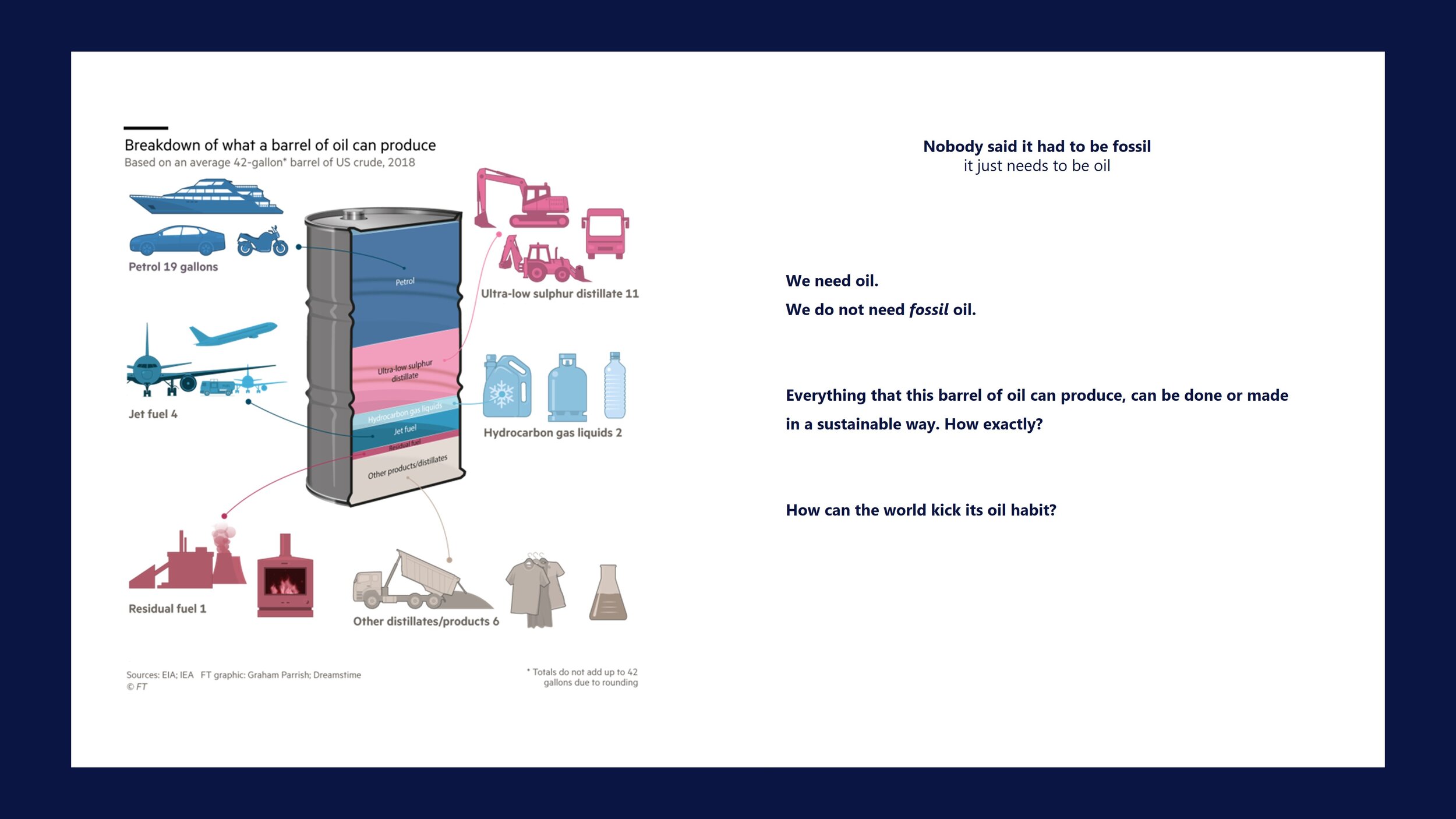

> (1)

It is indeed true that the world runs on oil. The cognitive bias that most people make however, is believing that it has to come from fossil feedstock. Everything that is made of oil can be made of biomass - plants - or even out of thin air. We covered this extensively in our blog series on how much biomass is needed to fuel the world.

> (2)

I always wonder. Why is $45 billion considered ‘an investment’ when it comes to oil and gas, while every dollar invested the energy transition or viewed as 'costs'?

What I hear a lot from people who work in the oil and gas industry, but also a lot of sceptics in society, is the question "who will pay for the energy transition?”. As if it were not the biggest investment opportunity in our history. Besides, it seems to me they forget the absurd amount of money our current fossil energy system costs already. According to the IEA, roughly $800 billion will be 'invested' in the oil and gas industry in 2021. If only we could use (part of) these funds and invest them in renewable power.

> (3)

Only two months later, oil demand plummeted and for the first time in history, oil prices became negative. Peak oil probably happened in 2019, as stated by BP later that year. It goes to show that predicting anything - in particular oil demand - is almost always wrong.

Why we are addicted

Oil is such a versatile product

Aside from the commercial interests of oil-producer nations and corporations, there is a practical question: how will the world function without a material on which we depend so deeply? Do alternatives exist for its myriad, and often invisible, uses? (4) And can any drop in oil usage happen quickly enough?

“The whole of human prosperity and wealth has been based on our exploitation of oil and other fossil fuels, so it is an almighty undertaking. To just remove them from our energy system within a decade or two is completely fanciful,” says Kingsmill Bond, an energy strategist at think-tank Carbon Tracker, which is calling on governments and financial institutions to align themselves with a low-carbon economy (5).

Throughout history, energy has been at the heart of how civilisations have prospered. For centuries, people burnt wood for warmth and for cooking. In the 19th century, coal emerged as the preferred fuel and enabled industrialisation. But it was in the early 20th century that crude oil — plants and animals that lived millions of years ago, compressed deep underground — propelled the mass transit of people and goods, fostered modern lifestyles and enabled higher standards of living than ever before.

Yet humanity’s improved wellbeing has come at the expense of the planet’s. The earth has warmed by 1 degree Celsius since pre-industrial times and is likely to heat up by another 2 degrees Celsius by the turn of the century — overshooting the targets of the 2015 Paris climate agreement. A 2018 UN Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change report showed warming beyond 1.5 degrees Celsius risked irreversible changes — from the mass extinction of species to extreme weather and ecosystem changes that threaten global stability.

History does not inspire confidence in humanity’s ability to wean itself off particular energies. Even after the world began moving from coal to other fuels, coal did not disappear. With the emergence of each new source, we have simply added it to the mix rather than replacing old ones. (6)

> (4)

Yes. The exact same oil, just not from a fossil source.

> (5)

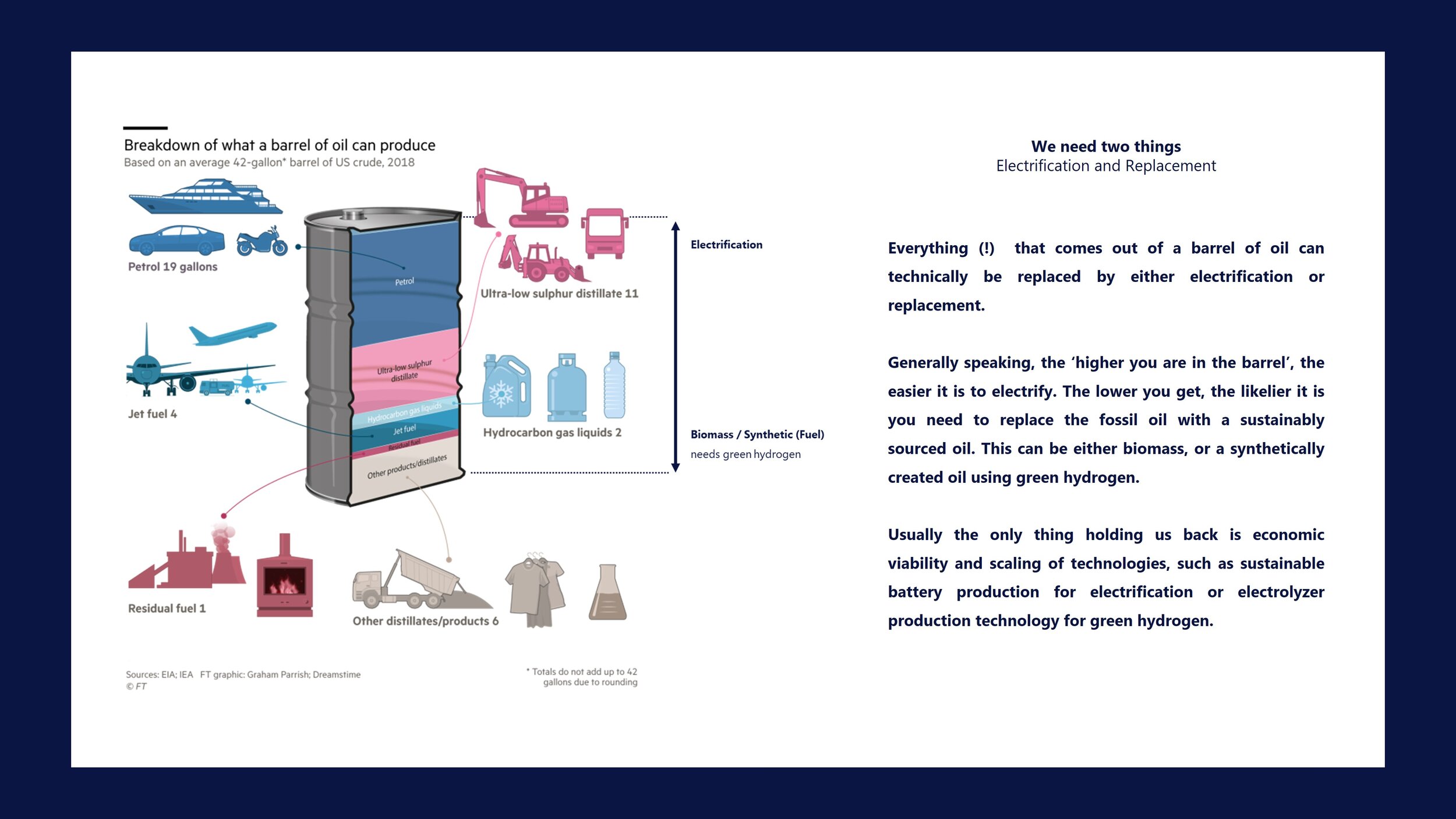

I believe the cognitive error we make here is assuming oil cannot be replaced. The fossil part can absolutely be replaced by means of electrification as well as bio- or synthetic fuels made out of thin air. We covered this in our three-part series 'Is there enough biomass to fuel the world'. Kingsmill Bond more openly addressed this fact when the corona pandemic was in full swing and decline of the fossil fuel industry became more evident, as discussed in The Future of Fossil Fuels 2020.

> (6)

Between 2000 and 2020, world coal consumption grew by 14636 TWh. During that period, Chinese coal consumption grew by 14642 TWh. The reason coal was still in the mix and growing, was because of China. Now that China is going carbon neutral, coal is seeing a dramatic decline. Most experts now agree that coal is done.*

Transportation

How to kick the habit

Cars, trucks and other road vehicles make up more than 40 per cent of global oil usage. When you add in aircraft, ships and trains, transport accounts for about 60 per cent. So any attempt to reduce our oil habit hinges on this sector. In the UK, petrol and diesel already contain up to 7 per cent biofuels but, given growing concerns about climate change and air pollution, governments are expected to enact stricter fuel standards.

The fastest way to begin curbing oil consumption would be to start with the easiest to eliminate areas. Displacing the roughly 4 per cent of demand used for power generation is seen as low-hanging fruit given more cost-effective — although not necessarily emissions-free — alternatives already exist, such as gas and renewable electricity.

Another quick win would be to use oil more efficiently. “We have to get ahead of the game,” says Anne-Marie Corr, BP’s fuels technology director and a 32-year veteran at the company (she retired in December 2019). A 5 per cent improvement in the average efficiency of new European internal combustion engine vehicles would lead to an annual reduction in carbon dioxide emissions of 1.8 million tonnes, says Corr, equivalent to replacing one million new cars with battery-operated ones.

Yet environmentalists say that striving to create the next hydrocarbon superfuel is merely tinkering around the edges of the problem.

“Fuel efficiency will do nothing to change the fleet,” says Mabey. He points to Daimler’s plans to stop developing internal combustion engines altogether. Electric cars are an alternative — but they are not yet a panacea (7). Their use may have grown rapidly over the past decade, but last year they still accounted for just 2 per cent of new cars sold. Even if every new car was electric from now on, analysts say it would take 15 years to overhaul the so-called global car park, which now numbers some 1.3 billion vehicles.

To accelerate electric car use, governments need to send the right economic signals. The UK this month announced plans to ban the sale of petrol, diesel and possibly hybrid cars by 2035. States would also need to bring down costs, incentivise research into advanced battery technology and roll out more charge points. Is goes without saying that the environmental benefits will only be truly realised if electric cars are powered by renewable electricity from wind or solar, rather than coal or gas-fired generation. Even then, most analyses indicate that electric, hybrid and hydrogen cars all emit less than regular fossil fuel burning cars.

Predicting how soon the world’s fuel habits will change is something that energy chief executives such as Ben van Beurden at Royal Dutch Shell are agonising over. “You could have one scenario that says, oil and gas is going to very quickly peak now,” he says. “It will become a diminishing percentage of the energy mix . . . but you can also go too early and too fast in investing in the [alternative] energy of the future.” He believes that prematurely giving up on oil and gas “is just not a smart strategy”. (8)

Growing demand for oil could be dented by electrifying two-wheelers, vans for “last mile” parcel deliveries and commuter buses, as well as increased ride-sharing. But displacing it in, say, heavy-duty trucks is harder. (9)

Oil’s unique qualities give it a stubborn advantage when it comes to engines, providing much greater energy density than lithium-ion batteries. Shipping and aviation — barometers of global trade — are other oil-guzzling industries where technological breakthroughs face cost and scalability challenges. They consume approximately 14.5% of all oil consumption worldwide.

For shipowners, liquefied natural gas still presents an emissions problem while battery power and alternative fuels such as ammonia and hydrogen bring their own issues. In aviation, there are high hopes of electrifying small and medium-sized aircraft, but for long-haul jets the challenge is greater. The potential use of biofuels is also controversial. (10)

There is a lot of talk about challenges and difficulties, but not a lot of doing the work that is needed to solve the issue. The solution seems clear to me. All land-based vehicles (regardless of size) are to be electrified. This applies to short-distance shipping and aviation too. Long-distance shipping and aviation would require less than 10% of oil use to be converted to biomass or synthetic fuel. The real challenge is scaling battery technology to such a level that it can provide the demand needed to convert the entire global car park and most vessels and airplanes. That is exactly what Tesla and Northvolt are doing, and exactly the opposite of what many players in the fossil industry are doing.

> (7)

Seems like something a doctor would say about a cure he would make no money on. Naturally, the fossil fuel industry would argue electric vehicles are not a silver bullet. The German auto industry seems to disagree however. Check out 'the Tesla Effect hits Germany'.

> (8)

It seems the corona pandemic made that decision for them. not only are habits changing faster than expected, a lot of investors are giving up on oil and gas as well (click here for a juicy story as to why and how or scroll down below). In general, I would argue that predicting these kind of changes and making fancy scenarios on what could happen in the future are a futile attempt at making the world seem more orderly. It is a modern form of dowsing for highly educated people, who never cross-reference actual findings with (their own) past predictions.

> (9)

Check out our blog on hydrogen vs. electric cars and why it is time for us to let go of the myth that heavy land-based transport - like trucks - are unsuitable for batteries.

> (10)

There are many controversies regarding biomass, which have been explored in our blog series on it as well (click here). Though I still fundamentally believe biomass is better than regular fossil fuels, biodiversity and human rights issues are serious challenges when it comes to the production of biomass. Nonetheless there are plenty of projects that tackle this problem head on, such as Groningen Seaports. There is even the option to produce biofuels from thin air, as is pursued by Heliogen, although it will probably take a long time before this is commercially viable.

Buildings and Industry

How to kick the habit

Two other sectors that account for significant oil use are buildings and industry. This includes heating and cooking as well as oil used for construction vehicles and industrial processes. Some of these are easier to displace than others. Oil might be better than gas for an industrial boiler as it has a higher energy density, while the diesel in a forklift truck is easier to eliminate.

More than 15 per cent of oil demand goes into non-combusted uses, including petrochemicals. A hefty chunk of this is for single-use plastics, found in packaging and drinking straws. Even if this falls thanks to plastic bans and wider recycling, huge investments are still being made in developing complex plastics and petrochemical substances. (11)

Full electrification of buildings is required to reduce fossil fuel dependency, though this can be challenging in very old or large buildings. Whatever the case, heat-pumps are the key to make buildings sustainable. Because of its versatile nature and its large power consumption, industry will be the most challenging sector to transform. Nonetheless, electrification will play a crucial role as well. Sustainably sourced hydrogen, called green hydrogen, is another crucial factor in order to ensure a sustainable future for industry.

Industry is more challenges as it uses a lot of oil for the production of all kinds of products and materials - as we saw previously - as well as for high energy purposes. That is why industry is one of the most challenging - and exciting! - sectors to decarbonize. Check out how this can be done in our third part of can biomass fuel the world. (link)

> (11)

And now the oil and gas majors are scratching their heads because they invested billions at a most unfortune time. Shell is even considering to exit US Shale operations, which are closely tied to complex plastics and petrochemical substances in the US. Click here for the story.

Oil and gas majors

How they are kicking the habit. Or not

BP started life in 1908 with an oil discovery in what was then Persia. Today, the company is rolling out electric charge points, sees itself as a player in renewable power and announced an ambition to reach net-zero emissions by 2050 or sooner. But for now it still generates the bulk of its profits from, and funnels most of its cash into, its legacy businesses. (12)

In August 2019, even as pressure in the west mounted for BP to demonstrate its low-carbon credentials, the company announced it had agreed to form a petrol station network and aviation fuels business in India with Mukesh Ambani’s Reliance Industries. Bob Dudley, BP’s then CEO, said: “India is set to be the world’s largest growth market for energy by the mid-2020s.” BP is not alone in pursuing new oil consumers in developing countries as demand begins to stagnate elsewhere.

France’s Total and the state energy giant Saudi Aramco are among foreign companies seeking a foothold in India as they bank on the country’s swelling middle classes to drive consumption. This points to a broader dilemma. Should countries that have not yet fully industrialised — where hundreds of millions of people endure poverty and a lack of basic infrastructure — not enjoy the same fossil-fuelled development that the west took advantage of? Or can they ‘leapfrog’ (13) this era that has brought the West its current wealth?

> 12

The same applies to many other oil and gas majors. Virtually all of them face rising pressure to push harder for carbon neutrality, mostly in the West. The below infographic shows which oil and gas majors have made accommodations to these pressures. More on that can be read in our blog ‘The Future of Fossil Fuels 2020’.

> 13

As this article of the financial times explains, the term “leapfrogging” is often applied to Africa, though it is also used to describe a path supposedly being charted by India, which is said to have skipped straight to a technology-driven economic model without the intensive manufacturing phase that spurred growth in Japan, South Korea and China. More on that in the section below.

Developing countries

Will they get addicted or can they leapfrog the habit?

The world’s addiction to oil is often compared with tobacco. But while smoking is something people can choose to do, using energy is not.

Mohammed Barkindo, secretary-general of Opec, the oil exporters’ cartel, said in a recent speech: “The almost one billion people worldwide who currently lack access to electricity and the three billion without modern fuels for cooking are not just statistics on a page. They are real people . . . Nobody should be left behind.” (14)

Some oil analysts, such as Christyan Malek at US bank JPMorgan, believe the reduction of tens of trillions of dollars in new oil investments amid a backlash against fossil fuels could create an “acute shortfall” in supplies and set oil prices on course to hit $100 a barrel. “The cost of energy will escalate if we can’t replace it with renewables and other non-oil sources quickly enough,” he says. “This will hurt western consumers . . . and, not least, emerging-market countries that can’t function without low-cost energy.”

Yet the cost of climate change could be far greater — and the world is running out of time.

The 2018 monsoon season in India saw some of the worst rainfall in decades. Hundreds of people died and the military airlifted food packages to stranded villages. Climate change is disrupting seasonal cycles — first bringing heatwaves and droughts, then floods and landslides. It is expected this will only get worse.

Yet despite experiencing some of the worst effects of climate change, India’s access to affordable fossil fuels remains a priority for its government. While the country has one of the most aggressive renewable power capacity roll-out programmes worldwide, it also needs cheap oil, gas and coal to meet energy demand that is forecast to more than double by 2040.

“In India, solar energy and other renewable sources of energy are becoming increasingly competitive,” says Dharmendra Pradhan, the country’s petroleum minister. But oil and gas, he adds, are commodities “of necessity — whether for the kitchens of marginalised populations or the globetrotting privileged classes . . . It would be difficult for us to give up fossil fuels completely at this stage of our developmental cycle — our per capita carbon emissions is low compared to the world average.”

India buys foreign crude for more than 80 per cent of its oil needs, which is why Pradhan believes the world’s third-largest oil consumer could be the “golden goose” for big Middle Eastern producers. Indeed, the prospect of rising demand in Asia and Africa partly explains why the UAE’s Adnoc aims to increase production capacity to five million b/d by 2030. The company is also part of a consortium developing a $70bn oil refinery project in the Indian state of Maharashtra.

> (14)

But do they really need fossil fuels to not be left behind? How about a solar panel to produce electricity of the grid in the most inaccessible places in the world? Would that not be smarter, more prudent and cheaper to do?

The international community

How they create policy to kick the habit

The challenge is huge.

In order to keep global warming “well below” a 2 degrees Celsius increase, the IEA says the world would need to stomach a fall in oil consumption to 67 million b/d by 2040. Environment analysts argue that we need to learn to survive on far lower levels — about 10 million b/d — and ultimately remove it from our energy system entirely.

Governments are beginning to take some action, from incentivising the purchase of low emissions vehicles to funding cleaner energy research. But the climate protesters scaling oil rigs, defacing energy company headquarters and denouncing the banks that fund crude production face considerable opposition. While coal and gas are starting to be displaced by lower-cost renewables in electricity generation, oil has a stranglehold over the transport sector, and the petrochemicals industry is a fast-growing consumer of refined products.

The IEA’s “sustainable development scenario” charts a way for the globe to avoid a temperature rise of more than 2 degrees Celsius while simultaneously guaranteeing widespread access to energy. But the agency is clear: this outcome would require “rapid and widespread changes across all parts of the energy system”. Who, or what, will prove most effective at driving such change is yet to be seen.

When the titans of global business and politics gathered in Davos last month, climate change was top of the agenda. Yet few could say how exactly the transition away from oil and other fossil fuels would take place. Instead, US president Donald Trump used his speech to assail environmental “alarmists”. The demands of climate advocates, he told reporters, were “unrealistic, to a point you can’t live your lives”.

Despite the challenges, not everyone feels hopeless about the world’s chances of transforming its energy future. Christiana Figueres was the Costa Rican diplomat who brought the leaders of 195 countries together in 2015 to sign the Paris agreement. The image of her in a roll-neck sweater and checked blazer, holding raised hands with then UN secretary-general Ban Ki-moon, marked a high point for multilateral efforts. Figueres, who was the UN’s top climate change official between 2010 and 2016, remains relentlessly positive. (She even leads an environmental organisation called Global Optimism).

Although the 2019 climate talks in Madrid ended in disarray, she believes the prospect of cleaner air, better health outcomes, more liveable cities and energy security will be enough to encourage governments to keep the deal alive. “I don’t demonise anyone,” she says by phone from a hotel in Davos. The blame game, she argues, is not helpful; countries that are dependent on the use of, or income from, fossil fuels are in a tougher place. “The important thing is: how quickly do you move beyond your starting line?”

Investors

How the dealers are switching their supply

In London, some fund managers — such as Natasha Landell-Mills — believe investors have a vital role to play in prodding corporations and governments. Last year, Landell-Mills’s company, Sarasin & Partners, which invests on behalf of charities, private clients and institutions, sold just over 20 per cent of its shares in Shell. In a letter to Shell’s chairman, she said its plans to grow oil and gas production were not aligned with global climate goals: “It cannot be in the interests of the millions of people whose long-term savings are invested in your company, for you to produce fossil fuels in such volume that planetary stability is threatened.” Sarasin has since sold a further 30 per cent.

Check previous - future of fossil fuels and roaring 20s

Diverting investment away from the fossil fuel industry — despite some companies being the biggest dividend payers in the world — is one way to curb its use and shift attitudes. The energy sector’s share of the S&P 500 today is already down to about 4 per cent, from more than 11 per cent in 2010. (15)

While pressure has largely been on the producers of fossil fuels, difficult-to-decarbonise industries, their financiers and auditors are also under scrutiny. “I ask companies, ‘Can you commit your business to aligning with net-zero emissions by 2050’? More often than not the answer is, ‘How do we do that when the future is so uncertain?’” Landell-Mills says. “Yes it is uncertain, but climate change is accelerating. So we all have a responsibility to act . . . Capital should flow towards solutions to climate change rather than causes.”

Figueres argues that while it is not up to governments to find the technologies to decarbonise the world, it is up to them to incentivise their development — particularly carbon capture and storage solutions. She believes states will be key to rolling out new energy infrastructure and increasing taxes on carbon-intensive fuels. “If governments place a price on carbon and this is increased over time, this is a very important incentive to decarbonise,” she says.

Around the world, individuals are taking to the streets and risking arrest to demand climate action, but their impact will depend on states and industries taking a lead. Figueres is encouraged by the signs that investors and corporations are beginning to act. “Governments have lost their mojo and have fallen behind compared to where companies are,” she says.

She notes that Larry Fink, chief executive of the world’s largest fund manager, BlackRock, wrote in his January letter to clients of the need to assess the impact of climate change on investment risks. “I believe we are on the edge of a fundamental reshaping of finance,” he wrote, announcing plans to increase the group’s sustainable assets tenfold from $90bn today to $1tn within a decade.

“Every day we see more and more companies and financial institutions that understand the risk of high-carbon assets,” says Figueres. “No matter where you look, the movement is in that direction.” (16)

> (15)

And it was going to hell in a handbasket not very long after. It was especially hard for Exxon. In December 2020, ExxonMobil announced that it would write off $20 billion on a number of natural gas fields as their value has declined dramatically. This historic billion dollar write-off of what was once the most powerful publicly traded oil company in the world - now kicked out of the Dow Jones Industrial Average (click here) - once again marks the dramatic change in the global energy sector.

> (16)

Make no mistake. The energy transition might be more of a ‘monetary transition’, in which entire monetary systems and trillions of dollars worth of investments need to be shifted (in a timely manner) in order to avoid a carbon crunch scenario. As correctly stated in the Financial Times article, a lot of (Western) investors are waking up to this reality. Click here for an article on regarding the monetary transition and an explanation on the carbon crunch scenario.

References & More Stories

Financial Times - Can the world kick its oil habit

Financial Times - African Economy: the limits of leapfrogging

Carbon Brief - Analysis: World has already passed ‘peak oil’, BP figures reveal