By Colin McKerracher, Head of Advanced Transport, BloombergNEF

General Motors just gave an update on its EV plans, including timelines for its Chevrolet Silverado electric pickup. The first deliveries of the work version of the truck are set to start soon, while the first editions for other customers will go into production in the fourth quarter.

The truck is a real monster, with a range of 400 to 450 miles and weighing in at more than 8,000 pounds. It accelerates from zero to 60 in just 4.5 seconds. While this has been hailed in some circles as a breakthrough in EV performance, it highlights a potentially troubling trend: the average range of EVs keeps going up and up.

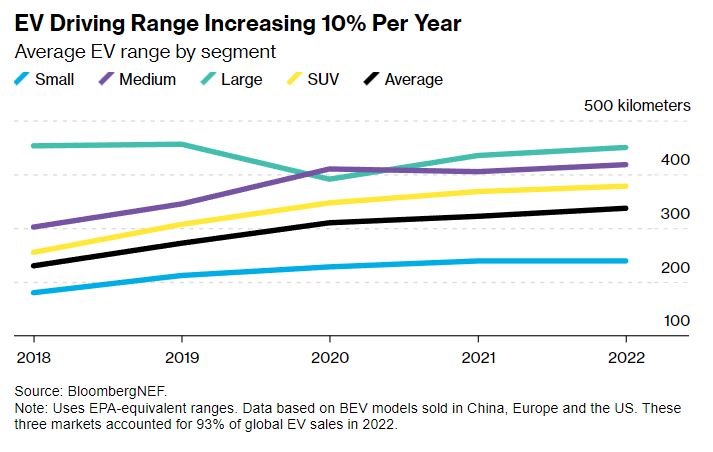

From 2018 to 2022, the average range of fully electric vehicle models globally jumped from 143 miles (230 kilometers) to 210 miles (337 km). US figures are even higher due to the combination of larger vehicles, longer driving distances and the dominance of Tesla, which sells higher-range models.

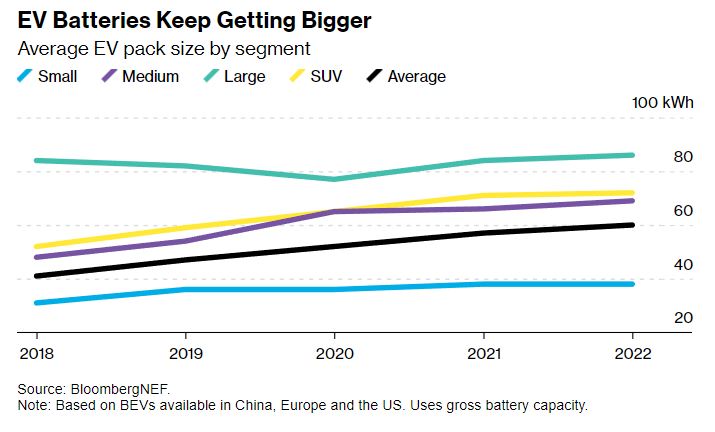

To deliver this, average lithium-ion battery pack sizes increased 10% annually over the same period, going from 40 kilowatt hours to 60 kWh. This rise shows no real signs of letting up. The wave of electric pickups that started with the Ford F-150 Lightning and will continue with the Chevy Silverado EV, the RAM 1500 REV and Tesla’s Cybertruck will keep inflating the US average in the years ahead. In these bigger vehicles, 100 kWh-plus battery packs are quickly becoming the norm.

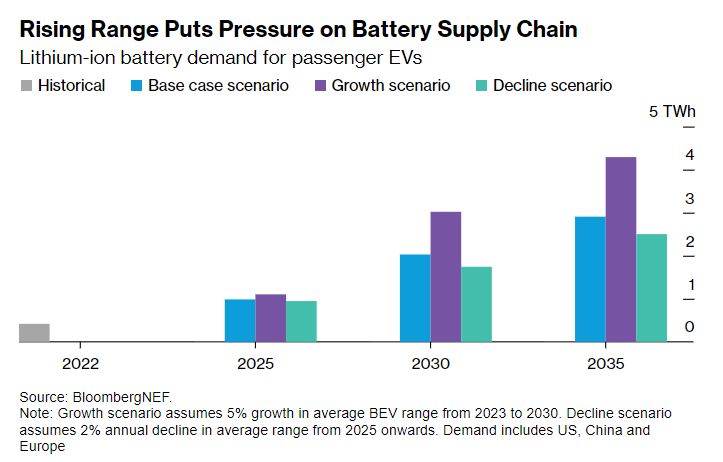

The increase makes sense from an automaker’s perspective — consumers in most segments say they want more range. But if left unchecked, this relentless rise in range and accompanying battery-pack sizes will eventually make it very difficult for the battery supply chain to keep pace.

In BNEF’s recent Electric Vehicle Outlook, we analyzed what happens to demand for batteries under different EV range scenarios. In our base case, average EV ranges plateau in the next few years between 250 and 310 miles (400 to 500 km), depending on the segment. Small city cars in markets like China, Japan and India stay much lower.

In the growth scenario, EV ranges in each segment continue to rise at around 5% per year out to 2030. That’s slower than the last few years, but still a significant increase. In the decline scenario, average ranges decline by 2% per year from 2025 onward as public charging improves and the EV market gets more price-competitive.

To arrive at the starting points, we looked at historical trends by model, segment and country for the big auto markets of US, China and Europe. In all of the scenarios, the average battery size needed to deliver a given amount of range falls slightly due to improvements in battery density and better overall efficiency of the vehicles.

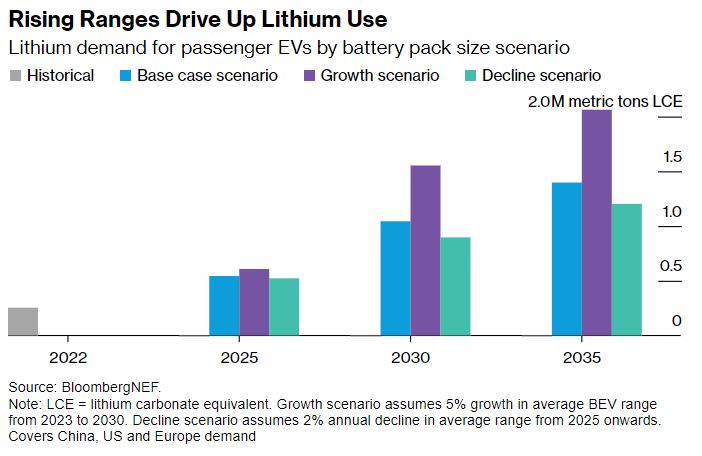

The results are stark. Battery demand in 2030 is almost 50% higher in the growth scenario compared with the base case, and 70% higher than the decline scenario. That maps directly onto demand for materials like lithium, which are already set to rocket in the years ahead. The affect on materials like cobalt is less significant because its use is already being pushed out by lithium-iron phosphate batteries and other formulations using lower amounts of the metal.

The high-range-increase scenario pushes the lithium market quite sharply into deficit by 2030 and could lead to a dramatic price spike similar to what happened in 2021 and 2022. Nickel supply also looks very challenging under the higher-range scenario.

So, what can policymakers do to get a handle on this? The first step is to focus purchase incentives on smaller, lower-price vehicles. Purchase incentives should come with a price cap, ideally one referenced at or below the average transaction cost of a vehicle in a given market.

More importantly, governments should be supporting large investments in public charging infrastructure. The best way to convince consumers that they don’t need excessive range and giant batteries is to show them that public charging options are plentiful, reliable and convenient. Each individual consumer over-buying the range they need is hugely inefficient by comparison.

Even if policymakers are unsuccessful in reining in this trend, economics eventually will. The electric Chevy Silverado has a 200 kWh battery pack. According to the latest battery pricing data, BNEF estimates that represents $25,000 to $27,000 of direct cost to GM.

Automakers are unlikely to make a competitive margin on a vehicle like this with battery prices where they’re expected to be for the next three to five years. If automakers can’t make money, they won’t push real volume.

There’s potential for innovations like solid-state or sodium-ion batteries to help alleviate these issues. But if ranges keep going up indefinitely, then volume and growth will eventually stall.