ImpactAlpha, August 25 – A growing ecosystem of Native-led entrepreneurs, lenders, financial intermediaries and nonprofits are driving Indian Country’s emerging economy.

“It’s kind of an unprecedented time,” exulted Heather Fleming of the Navajo business incubator and lender Change Labs on this week’s Agents of Impact Call, “Mobilizing capital in Indian Country.” Tens of billions of dollars are becoming available to tribal communities from recent federal legislation in the US, including the American Rescue Plan, the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law, and the Inflation Reduction Act.

“I’m anticipating that there’s going to be all of these venture funds out there soon that are specifically for Native communities,” said Fleming. “These are conversations that have never been had within our tribes, so it’s exciting to see this change happening so quickly.”

Critical capital gaps need filling, however. Indigenous communities are woefully underinvested. And while there are now hundreds of Native-led financial institutions, fund managers and other organizations ushering in capital and resources, philanthropy and impact investors need to step up.

“I would invite investors and impact investors to think about how they can stretch your learning inside of your organization to provide grants and investments?” said Kate Finn of First People’s Worldwide, which published the report, “Indigenizing Catalytic Capital.” “What does it look like to give a loan guarantee? What does it look like to do program and mission-related investments? What can you do to give a recoverable grant?”

“Let’s stretch our capacity,” she added, “because Indian Country is growing so quickly.”

Catalytic grants

Conversations about catalytic capital conversation often center around investments, but grants can be crucial instruments to unlocking new channels of capital, including commercial investment.

The reestablishment of a tribally-owned buffalo herd on the Rosebud Sioux lands of South Dakota “wouldn’t be possible” without early grant funding, said Clay Colombe of Sicangu Co., which oversees the 1,000-head herd. The organization secured grant funding from the World Wildlife Federation for a feasibility study.

“It wasn’t a proven concept, but we had to make sure it would work. We didn’t have the dry powder there to invest in that,” said Colombe. “Grants are an effective way to get that pre-development [work done] and allow for a safety net.”

“There are a lot of technological gaps that we need to fill,” added Brett Isaac of Navajo Power, which is developing utility-scale solar power plants on tribal lands with a model that ensures tribes get a direct stake in the economic upsides. Tribal communities often don’t have the credit ratings or financial strategies to bring in the tens or hundreds of millions of dollars required to finance such large-scale projects, even though more funding than ever is available for them.

“There’s a large need in our country to support Indigenous communities to take advantage of things like the Inflation Reduction Act. The Department of Energy’s Loan Program Office has existed for over a decade, yet has issued zero loans [on tribal lands] in its history,” said Isaac. “Part of that is because an intermediary such as Navajo Power didn’t exist. There wasn’t a place for communities to seek out that initial guidance and capability.”

Investing through intermediaries

Both the “Indigenizing Catalytic Capital” report and participants of the call stressed the crucial role that Native intermediaries play in getting more capital to Native entrepreneurs and initiatives.

“Native community development financial institutions are the economic engines and pillars of their communities hands down,” said Chrystel Cornelius of Oweesta Corp., a lender and technical assistance provider to Native CDFIs. “When we see an individual that wants to repair their assets, they want to climb the upward mobility ladder of financial stability, there’s no other organization or programs that are doing this for Indigenous peoples. CDFIs have been instrumental in the economic growth of the communities where they’re located.”

Oweesta recently provided a loan to a CDFI in Hawaii, TK, that provides home and business loans. During economic downturns, and after disasters like the Maui wildfires, such proximate organizations are essential to helping communities rebuild, Cornelius added.

“It’s the Native intermediaries who have that trusted relationship and who can build that capital,” said Finn.

Telling the story

Lack of information sharing and deal transparency has been a key barrier to catalyzing capital to Indian Country.

“There are a lot of investors and foundations and others that are in partnership that are doing this work, and they’re not telling their story to their peers,” observed Jen Astone of Integrated Capital Investing and co-author of “Indigenizing Catalytic Capital.” That has a “drag effect” on investments into Native communities and enterprises.

“Not only is there the invisible economy in Native Country, but also there’s the invisible philanthropist doing this really hard work of making patient, low-cost, long-term loans, and they’re not touting their story,” said Astone. “There’s just so much opportunity for investors to follow their peers and to build stronger coalitions and to move more money into Indian Country. That’s my challenge to the field.”

For new opportunities, “I don’t think you can overemphasize the importance of being first in on some of these really important efforts,” said John Balbach of the MacArthur Foundation, which is building its own portfolio of investments in Indian Country and supported the report as a member of the Catalytic Capital Consortium.

Balbach emphasized a key piece of the research, which stressed the need for supportive, constructive and trusting relationships between tribal communities and funders.

“I love the term ‘right relationship.’ That’s something that we at MacArthur are really trying to understand,” he said. “It’s so important to move at the pace of trust, recognizing the financial trauma that’s inherent in a lot of these discussions.”

Added Finn, “There’s a call here for philanthropy, for investors to share as much information as they can and really to put all the cards on the table for Native entrepreneurs so that people can see what’s available to them in the deal-making structure, what they can do, how [funders] can support their solution with capital instead of changing their solution to access capital.”

“Transparency,” she continued, “allows everyone to see that these kinds of creative capital deals can happen, and will happen.”

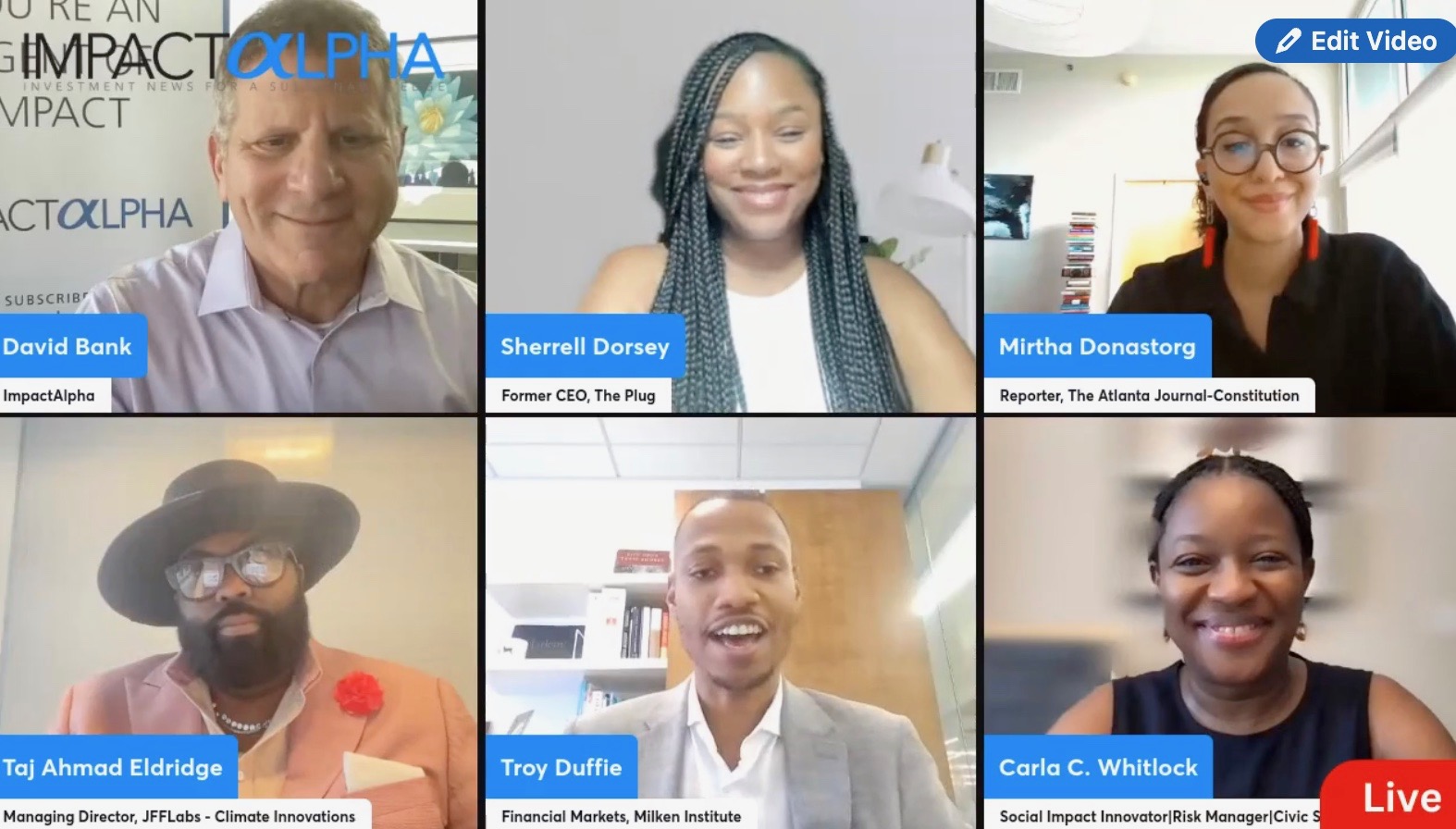

Agents of Impact

Agents of Impact tuning into the call shared with fellow participants their professional as well as tribal affiliations and lands they called in from.

Navajo Power investor Tory Dietel Hopps called in from Wabanaki lands in Maine… Jael Whitney, who runs the Indigenous Communities Fellowship at MIT Solve, is a member of the Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma… Zineb Touzani of Mission Investors Exchange, called in from Tampa, Fla. – Seminole land.

Keoni Lee of Hawaii Investment Ready greeted participants in Hawaiian… Lauren Grattan of Mission Driven Finance, also Native Hawaiian, and called in from Ute lands… Jael Kampfe of Indigenous Impact Co. and the Mountain-Plains Regional Native CDFI Coalition cited her work on the Lakota, Apsaalooke and Northern Cheyenne lands.

Eric White represented the Bush Foundation, which serves 23 Native Nations and the states of Minnesota, North Dakota and South Dakota – Anishinaabe and Dakota lands… Ben Harris of the Sustainable Food Lab called in from Vermont, Abenaki land.