The spotlight

Yesterday, the U.S. government released a massive report analyzing the latest climate science and the ways in which this multifaceted crisis is impacting life in every part of the country. The Fifth National Climate Assessment, or NCA5, is the latest in a series of national reports published every several years since 2000.

Since the Fourth National Climate Assessment in 2018, a lot has changed. This new report focuses not just on how bad things could get if we don’t take decisive action to reduce carbon emissions, but on how bad things already have gotten, with climate impacts hitting every part of the country and threatening the things Americans hold most dear. But the report also reflects just how far the climate conversation has come in the past five years — and how every part of the country is taking steps to address and adapt to the crisis we’re facing. (Read our summaries of some of the key impacts and solutions highlighted for each region.)

Some other things that have changed since the last report: NCA5 is the first assessment that will be fully translated into Spanish. Visual artists were invited to contribute works that are sprinkled throughout the report, for the first time. And, in another first, this report includes mention of LGBTQ+ populations and the unique climate vulnerabilities they face.

“Because the National Climate Assessment is really based in peer-reviewed, evidence-based literature, there needs to be that type of research body there before it can even get into or be considered for the National Climate Assessment,” says Leo Goldsmith, a climate and health scientist who has been part of creating that body of research on LGBTQ+ people and climate impacts. He was also a technical contributor to the report’s chapter on human health (and was featured on this year’s Grist 50 list).

Goldsmith (who uses he and they pronouns) got interested in the question when they took an environmental justice course as a graduate student at the Yale School of the Environment. “As somebody who is pansexual and a transmasculine, nonbinary person, I did not see sexual orientation and gender identity being addressed in the literature as populations that are at risk for climate change,” they say. At the time, there was essentially no research in the U.S. on the disproportionate burdens and unique risks that queer and trans people face from climate impacts. Yet he knew, from lived experiences, that queer people face many of the same social, economic, and health disparities that other marginalized groups do.

The final paper Goldsmith wrote for that class caught his professor’s attention, and together, in 2021, they published “Queer and Present Danger: Understanding the Disparate Impacts of Disasters on LGBTQ+ Communities.” That same year, with another professor, he published “Queering Environmental Justice: Unequal Environmental Health Burden on the LGBTQ+ Community.”

The first paper is cited as a reference in the National Climate Assessment — and a section in the human health chapter titled Sexual and Gender Minorities’ Health, which Goldsmith wrote, describes some of the social, economic, and health disparities that LGBTQ+ populations face, making them more vulnerable to climate impacts. For instance, the report notes that disaster response plans “increasingly rely on faith-based organizations as first responders during disasters, which in some cases have blamed SGMs for devastating hurricanes and wildfires as a punishment from God.”

Goldsmith is now a doctoral student at Yale, where he intends to build on this work. We spoke with them about their contributions to NCA5 and the nascent body of research around LGBTQ+ populations and climate change. His responses have been edited for length and clarity.

![]()

Q. What do you feel is the significance of the National Climate Assessment including research on LGBTQ+ populations for the first time?

A. Having that in the report means that this is something that is valid, and that LGBTQ+ communities are a vulnerable population, with the backing of the peer-reviewed literature. If it wasn’t scientifically rigorous, it wouldn’t be included. And the reason why I’m emphasizing that is because I feel that folks may not think that LGBTQ+ individuals are actually disproportionately impacted — due to what’s called the “gay affluence myth.” We primarily see in the media that LGBTQ+ individuals are white, wealthy, gay, cis men. [We’re] not really seeing the entirety of diversity within the community, and ways that they could be disproportionately impacted.

Having that in the report means that, now, community members can take that and use it for educational purposes or advocacy purposes. Decision-makers can use that information to create evidence-based policy. Academics and researchers can use that as a basis of [realizing that] there’s so much more research that needs to be done, and maybe they’ll include queer and trans communities within their research.

Q. Could you give an overview of some of the key vulnerabilities and disparities that LGBTQ+ people face with disasters and climate impacts?

A. Yeah, absolutely. So first I’ll mention that LGBTQ+ individuals are more likely to live in poverty, be unhoused, have a mental illness, have a chronic illness, have no health insurance, and also are much more likely to be incarcerated. All of those put people at higher risk for more negative experiences and impact during and after disasters.

When a disaster does hit, LGBTQ+ individuals [often] aren’t able to access the services and resources that they need in order to protect themselves or move back into their living situation. For example, during Hurricane Katrina, there were two Black trans women who went to use a shelter in Houston, Texas. And when they tried to use the bathroom of their gender, they were arrested for doing so.

There have been other stories of folks who weren’t able to access the medications that they needed — hormone replacement therapy, or medications for HIV. In addition, individuals may have been separated from those that they consider family. LGBTQ+ individuals are much more likely to be disowned by their biological family. And so they tend to create a group of relationships of strong ties that aren’t biological, but are what’s considered chosen family — that’s just as valid as biological family. But that’s not something that is considered as part of the policies and laws in place for disaster relief and response.

[Then] there’s federal policies such as the Robert T. Stafford Act, section 308, which is the nondiscriminatory policy that covers all of the different disaster response that the agencies do. They only include the term “sex” in relation to gender and sexual orientation. So that can be interpreted differently depending on the administration that’s in office at that time. Currently, it means sexual orientation and gender identity, but in a different administration, it might just mean that gender is only men and women, and that marriage should only be between a man and a woman. And that can affect the ways that the agencies are able to provide services and resources.

Q. Speaking of language — I noticed that the report uses the term “sexual and gender minorities.” Is that preferred technical speak?

A. The authors [and I] had a discussion on this, because we wanted to make sure that we were using the most accurate term for the report. Because there are so many different ways that people identify themselves — even in the literature, and also just within communities — “sexual and gender minorities” kind of encapsulates all of those different acronyms that people might use for themselves, like LGBTQ+ or LGBT or LGBTQIA or LGBTQ2S. So we just wanted to be as broad as possible.

You’ll see in the chapter, we use the term “Latinx,” and [in the Spanish translation] it’ll be “Latine.” That wasn’t something that was mandated, it was something that the authors chose. And we did that because we wanted to incorporate language that most represents LGBTQ+ communities and is most inclusive.

Q. So we’ve talked about risks. What are some of the solutions or strategies you have researched that could help address the disparities LGBTQ+ populations face with climate and disasters?

A. I just want to preface by saying this is all my own personal thoughts, and not the federal government’s. But some solutions that people can take — one, there need to be anti-discrimination policies that explicitly include sexual orientation, gender identity, gender expression, and sex characteristics. And that especially needs to happen within section 308 of the Robert T. Stafford Act [for disaster relief and emergency assistance].

There also should be cultural competency training on sexual orientation and gender identity among all disaster organizations, or health organizations that are going to be working with disaster survivors. And disaster organizations should start figuring out how they can include LGBTQ+ individuals from the very beginning in their planning and preparedness. FEMA and other disaster organizations have advisory boards — but not one that’s focused on LGBTQ+ individuals.

In addition, [we should be] looking at other places that LGBTQ+ people feel comfortable going to as emergency response shelters or temporary shelters. So instead of going to maybe a shelter where trans folks have to be separated based on their sex assigned at birth, they can go to an LGBTQ+ community center where they can feel safe.

And then for healthcare, for example, there was a report that came out through the Center for American Progress saying that there’s a large percentage of transgender individuals in particular that are either refused care and service or discriminated against when they receive care and service. And this is especially true for trans people of color. So cultural competency training needs to happen for doctors, too, especially those that are doing disaster medicine. In some states, there are clauses that allow for medical professionals to basically refuse care to LGBTQ+ individuals on the basis of their religious beliefs. Those types of policies need to change.

And then the last thing I’m gonna say is that a policy — a law like the Equality Act, which basically prevents discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation and gender identity — needs to be passed. What we’re finding now is that it’s a patchwork across the United States, which states have anti-LGBTQ+ laws and which states don’t. Individuals who are living in states with a high number of anti-LGBTQ+ laws, that’s really affecting folks’ mental health, physical health, economic well-being — and that puts LGBTQ+ individuals at even more of a disadvantage when it comes to disasters.

Q. Do you think research can help build the political will for protections like those?

A. I definitely think so. What I have found working with the agencies and talking to folks in the agencies, if there is no research or peer-reviewed literature on a subject, they can’t really do anything about it. It needs to be backed up with evidence that where their attention and their money is going is actually something that will be useful and will benefit folks. There’s a lot of really good intention, but unfortunately because it’s just so under-researched, it can kind of fall away.

I do want to mention that the Commission for Environmental Cooperation, which is the secretariat for the three environmental ministries of North America — so that includes the Environmental Protection Agency — has recently gotten more interested in learning about LGBTQ+ communities and disaster and environmental impact. They invited folks a few weeks ago to talk through what their strategy could be to do that.

From the EPA and FEMA and [the Department of Health and Human Services] — all three agencies that do emergency management and disaster work — I have seen that there’s been at least a little bit of progress. But we definitely need much, much more research. And not only research, but advocacy. The folks on the ground who are saying, “This is important and this needs to be listened to” — they’re the most important piece out of all of this.

— Claire Elise Thompson

More exposure

- Read: Grist’s roundup of the most salient solutions and adaptations discussed in the National Climate Assessment, region by region

- Read: Grist’s roundup of the most salient risks and impacts discussed in the National Climate Assessment, region by region

- Read: what the NCA has to say about the disproportionate risks that Indigenous peoples face from climate change — and why self-determination is a necessary solution (Grist)

- Read: a previous Looking Forward newsletter about the field of queer ecology and the lessons it offers for climate solutions

- Watch: a trailer for Fire & Flood: Queer Resilience in the Era of Climate Change — a docuseries that will ultimately be available for free online (Queer Ecojustice Project)

- Watch: how the disability community is also uniquely vulnerable during disasters (PBS NewsHour)

A parting shot

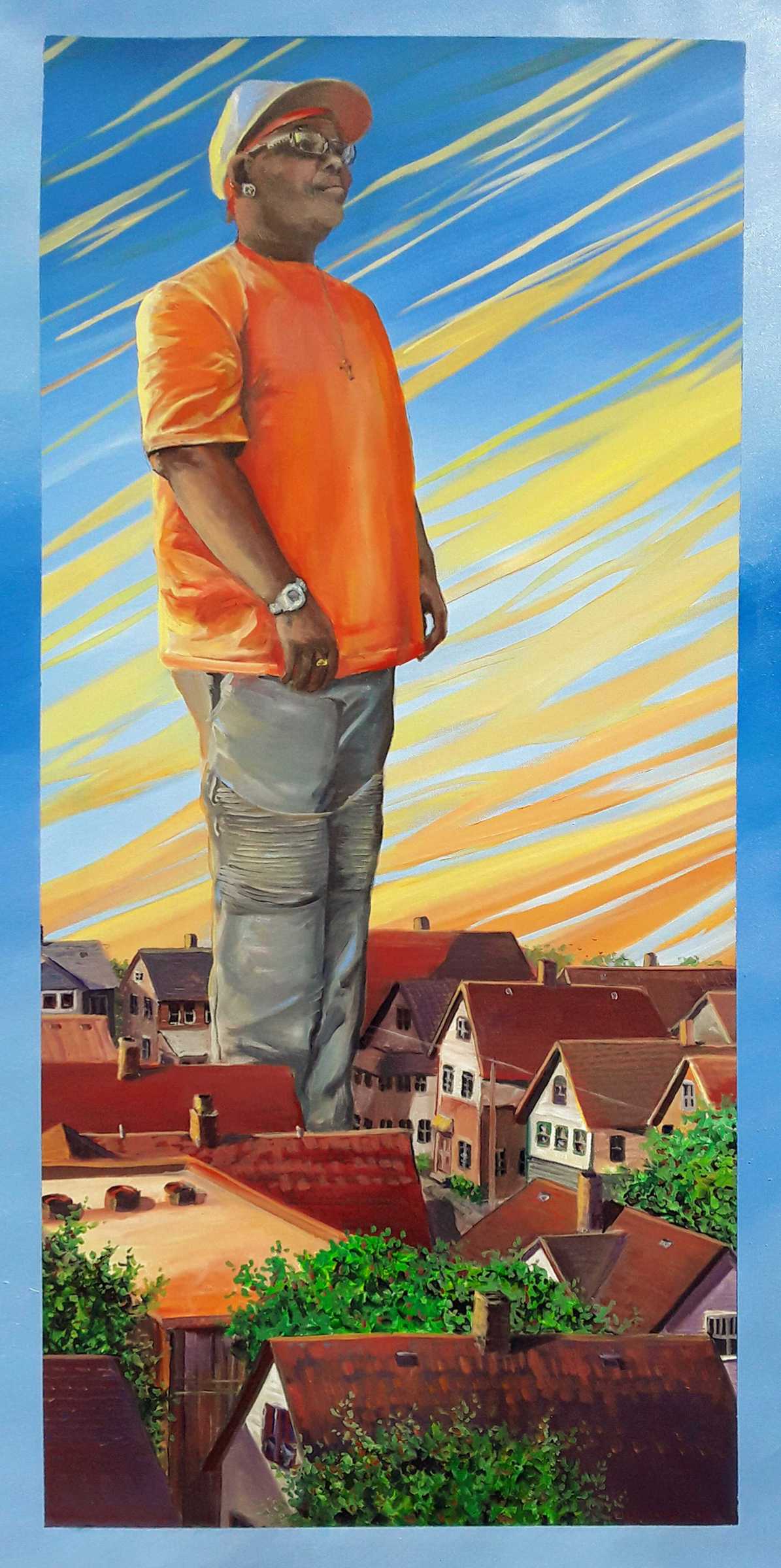

The 2023 National Climate Assessment put out a call for visual artwork to accompany the scientific report. Organizers received over 800 submissions, and the final gallery features work from 92 artists, representing all 10 regions covered by the report. This piece is titled “Cheryl.” Painter Ellen Anderson wrote in her artist’s statement: “Cheryl is a very real person in Milwaukee, Wisconsin. She works at a social services nonprofit and is a member of our gay community. I painted her to show her confidence and triumph over urban challenges. This painting depicts the density of urban life and the spirit of the individual in it. The power of the individual, for climate change, social change, and personal change is embodied in this painting.”