A CO2-based desalination technique might permit the use of municipal wastewater as an alternative freshwater source, in a manner that is less energy-intensive than conventional desalination

Turning cities’ wastewater into usable freshwater is an environmental win. All the more so when a greenhouse gas—carbon dioxide—is used to power the process.

“Natural freshwater resources—lakes, rivers, groundwater—are under severe stress due to adverse impacts of climate change, coupled with gradually increasing population in metropolises around the globe,” explains Dr Arup SenGupta, whose team has developed the method.

“Municipal wastewater treatment plants in large cities are insulated from the negative effects of climate change, and treated wastewater can serve as a potential water source, provided appropriate sustainable and cost-effective technologies are available.”

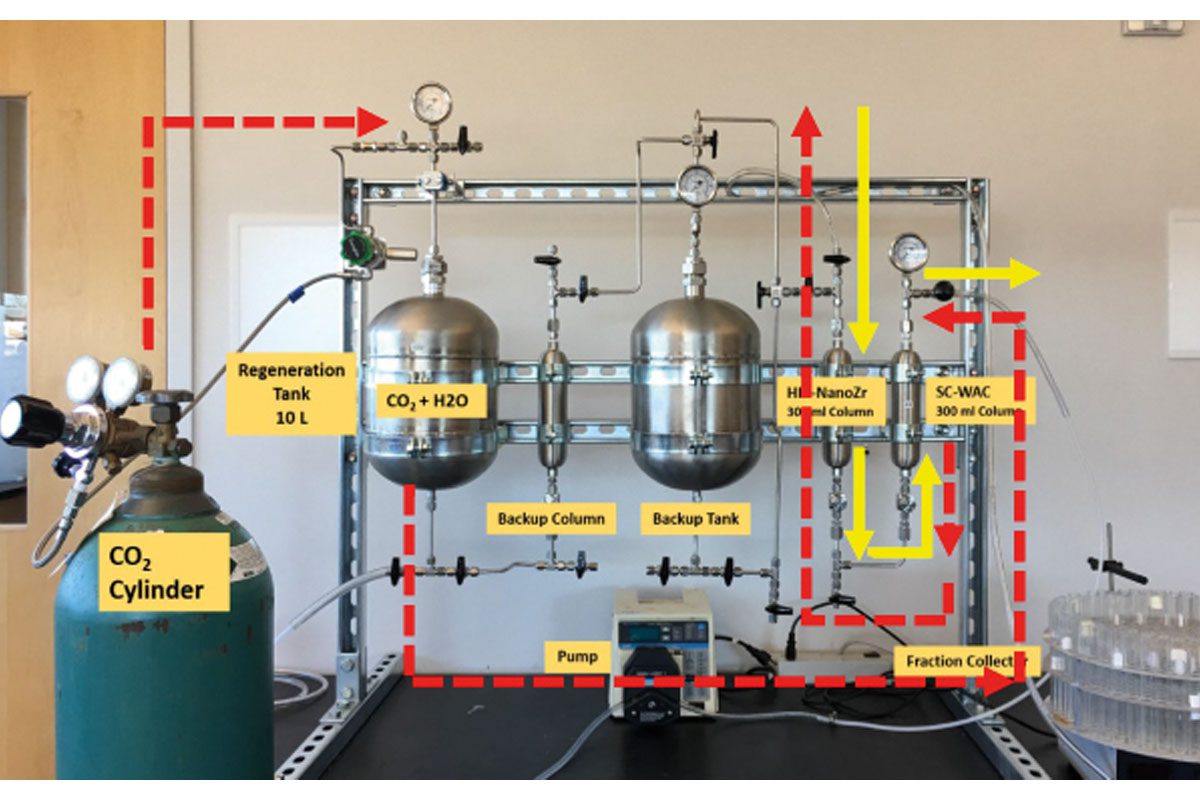

In 2019, SenGupta and his doctoral students at Lehigh were awarded a US patent for the system, described as a CO2–driven ion exchange desalination process, called HIX-Desal, which he calls “a legitimate candidate to transform wastewater into usable water.”

Less energy than desalination

Existing wastewater desalination systems, such as those employed in California by the Orange County Water District in the city of Fountain Valley, use semipermeable reverse osmosis (RO) membrane processes that require a separate electrical and/or mechanical energy source. Approximately 1 to 1.5 kWh of energy is required to produce 1000 liters (264 gallons) of treated water, or just over the average amount three Americans use at home each day.

HIX-Desal harnesses the unique chemistry of CO2 to replace that energy requirement. And, SenGupta says, when paired with existing generators of carbon dioxide (such as cement plants and anaerobic waste digestion processes), the process can be effectively carbon negative.

“Carbon dioxide, which is safe to handle and nonhazardous, can serve both as a weak acid and a weak base concurrently in a single process for desalination,” he says, “avoiding the need for energy-intensive RO membrane processes.”

The system also reduces the water pretreatment required to protect the membrane in reverse osmosis setups, resulting in cost savings.

Real-world tests

Initial studies of HIX-Desal were conducted on Lehigh’s doorstep in collaboration with the City of Bethlehem in Pennsylvania. SenGupta’s team, which includes graduate student Hao Chen, and Nick Donato, an undergraduate research scholar, hope to gain insight into the energy advantages and scalability of the technology in a new collaboration with the Lehigh County Authority’s wastewater treatment plan in neighboring Allentown.

The two-year project was recently funded by the US Bureau of Reclamation, a federal agency under the US Department of the Interior, as part of a $5.8 million investment in 22 laboratory and pilot-scale desalination research projects to enable broader deployment of desalination and recycled water technologies.

The Kline’s Island plant in Allentown treats nearly 35 million gallons every day, says SenGupta, and ongoing investigations seemingly shows that the salinity of the treated wastewater can be reduced by more than 60 percent by the HIX-Desal process, without requiring any reverse osmosis. If successfully deployed using carbon dioxide from the facility’s anaerobic digester, he explains, the technology could lead to a savings of approximately 1 million kWh per day (or about enough energy to power 94 U.S. homes for a year).

Removing phosphate

Recent tests appeared to confirm another potential benefit: In July 2021, SenGupta’s team collected samples of treated wastewater from the plant and completed the first cyclic process. The results, he says, revealed that the phosphate (responsible for algae growth and eutrophication) present in the plant’s wastewater can be selectively removed, concentrated, and recovered as a potential fertilizer in pure form, ready for direct field application.

SenGupta says he sees huge potential in validating the use of waste carbon dioxide – whether from landfills or gas turbine exhaust – to desalinate municipal wastewater and water from other impaired sources (such as what’s used for cooling applications in power plants or industrial facilities).

“This concept forms the basis of a circular economy, in which waste from one process is a potential resource in another process,” he says. “It’s a great challenge, but one that’s exciting as well.”