Singapore made a new pledge last year to reach peak greenhouse gas emissions of 65 million tonnes by 2030, halving that amount by 2050 and achieving net-zero emissions “as soon as viable in the second half of the century”.

To help achieve those goals, new proposed legislation would give Singapore’s Energy Market Authority (EMA) and Ministry of Trade more powers to ensure companies improve energy efficiency and to increase renewable energy supplies, including solar power imported from neighbouring countries. However, Singapore’s climate goals hinge on its ability to wean itself off its reliance on natural gas.

The Energy Bill legislation presented for public consultation in August, proposes amending the existing Energy Market Authority of Singapore Act, Electricity Act and Gas Act. Once in force, it has the potential to etch away at the country’s gas dependency. Singapore produces about 94 per cent of its electricity from natural gas.

The raft of amendments looks to grant the EMA more muscle that will force electricity generation companies to improve their efficiency and shift towards cleaner and more efficient modes of power generation. If passed, the EMA will be allowed to incentivise low carbon and energy efficient technology. The changes would also impose new obligations on “responsible persons” to inspect gas installations regularly, along with required maintenance and repair work.

Other proposed changes will enable the EMA to “raise capital and issue bonds” in order to build, buy and run critical infrastructure. That step would see the EMA effectively becoming a utility company, as well as a market operator. An industry source told Eco-Business that EMA’s move to become a direct market participant in this environment is being closely watched, although it’s too early to say how the sector will respond, and who the winners and losers will be.

A handful of responses as part of the public consultation, published on 4 October, largely expressed support for the changes. Some expressed concern about the EMA consolidating its authority as a state utility and market operator. The changes, the feedback said, would allow the EMA to “act as both regulator and owner/operator of the generation units, and these units would compete with existing units in the Singapore Wholesale Electricity Market (SWEM) and depress wholesale electricity prices.”

The proposed changes are part of Singapore’s wider attempts to reduce the country’s carbon emissions. In 2019, Singapore was the first country in Southeast Asia to introduce a carbon price though the Carbon Pricing Act in a bid to incentivise emissions reductions. The EMA recently announced plans, dubbed 4 Switches, to encourage cleaner power generation and increase low-carbon generation sources.

The energy authority intends to promote strategies that improve efficiency at power plants, deploy energy storage systems to address intermittent energy flows and explore opportunities to use regional power grids. Further into the future, the country’s EMA plans on directly importing low-carbon electricity from other countries, using high-voltage direct current (HVDC) undersea transmission lines.

The final ‘Switch’ involves somewhat speculative carbon capture, utilisation and storage (CCUS) technology which captures carbon and either stores it or turns it into useful energy products. Critics maintain that the technology remains unproven and may never deliver the vast emissions reductions needed. Chevron’s Gorgon project, a US$54 billion liquefied natural gas (LNG) plant equipped with CCUS, a facility in Western Australia, failed to meet a requirement to capture and bury at least 80 per cent of the project’s emissions during its first five years of operation, blaming “technical challenges”.

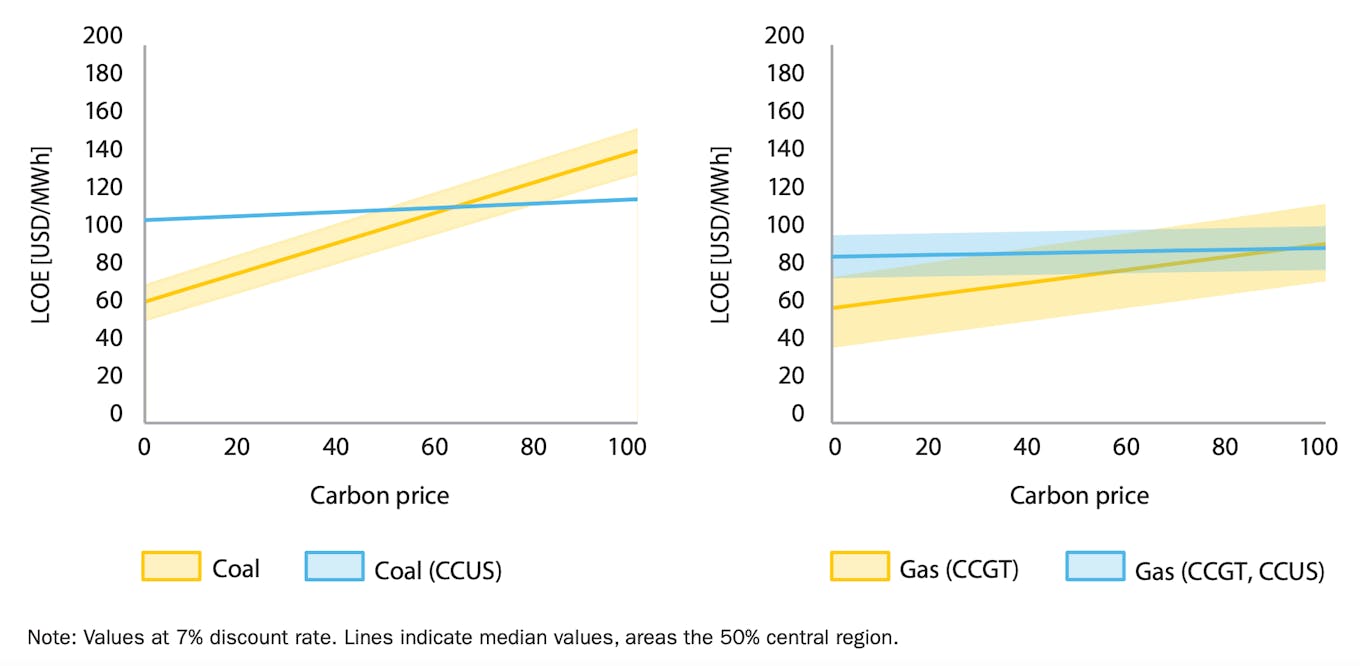

The technology is also costly. The International Energy Agency said in a report in June that Southeast Asia needs to invest US$1 billion per annum and capture 30 million tonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent (CO2-e), by 2030. Singapore is spending US$36 million on low-carbon energy solutions including hydrogen and CCUS until 2025. IEA estimates that the cost of CCUS from power generation is US$50-75/tonne (although this is a global average which includes coal plants). Combined Cycle Gas Turbines (CCGT) with CCUS would produce electricity at an average cost of US$91/megawatts per hour (MWh), reckons the IEA , compared to Combined Cycle Gas Turbines (CCGT) without at US$71/MWh.

Levelised cost of energy with and without CCUS for various carbon prices. Image: IEA, 2020.

“For gas-fired CCGTs, only carbon prices above USD 100/tCO2 would make plants with CCUS competitive. At such high carbon prices, renewables, hydroelectricity or nuclear are likely to constitute the least-cost options to ensure low-carbon electricity…Depending on national circumstances, with sufficiently high carbon prices, CCUS could be a possible complement in certain low-carbon power mixes,” the report said.

Gas stays on the table

Singapore sits in a region where energy demand growth is likely to remain strong but is also reliant on fossil fuels. Fossil fuels account for around 80 per cent of primary energy demand in Southeast Asia, according to the IEA, up from two-thirds in 2000. Despite global efforts to reduce a reliance on fossil fuels, gas is likely to remain a key energy source for the city-state for decades. It will require “significant progress” in gas efficiency to “greatly reduce gas needs” according to research on Singapore’s gas market by Italian think-tank, Istituto Affari Internazionali.

After record spikes in electricity prices in the early 2010s, power generation companies rushed to build new gas generators in Singapore. Energy bills have since dropped by more than two-thirds, but at the cost of expensive, under-utilised and polluting fossil fuel assets.

“The current state of the Singapore electricity market is that it’s hugely overbuilt generation capacity, and that it’s almost all gas,” said energy economist Prof. Anthony Owen.

Between 2011 and 2018, Singapore’s electricity generation capacity grew by 27 per cent, taking the total electricity available from 9.9 gigawatt (GW) to 13.6 GW. Almost all the additional capacity came from natural gas generators, a significant source of greenhouse gas emissions (GHGs). Gas imports have also grown by a third over the same period.

However, capacity eclipsed Singapore’s demand for electricity which only grew 11 per cent over the same period, leaving gas power generator companies to compete on price in a crowded marketplace. Although the market is dominated by the ‘Big 3’ generation companies of Senoko Energy, Tuas Power, and YTL PowerSeraya, these incumbents are increasingly losing their market share to smaller, nimbler entrants with more modern technology. Newer plants could produce 1,000 MW over the next five years, according to an industry source.

The newer, more efficient gas turbines are the winners in the current environment, but many power generation companies operate under long-term ‘take-or-pay’ gas supply contracts, which effectively lock the buyer into receiving gas or paying a penalty. That means that the older generators are sometimes forced to burn gas even when it’s unprofitable or unnecessary, according to a recent Deloitte report.

EMA has said that almost all of the gas turbines will be retired over the next two decades. In the meantime, whether older gas generators will continue to be replaced by newer, more efficient ones, or by renewable energy, remains a question to be answered, complicated by EMA’s potential intervention.

Singapore’s “insufficient” climate targets

A Climate Action Tracker report in September found Singapore’s climate target and policies as “critically insufficient” - the worst rating on a five-point scale. “Singapore needs to set a more ambitious target for emissions reductions and establish associated policies to improve its CAT ratings,” the independent scientific analysis said. The government has subsequently told local media that the report had not “fully accounted” for Singapore’s “unique challenges” - namely, space limitations on land to pursue solutions such as hydro, nuclear and solar power.

Solar capacity grew from 15.3 MW in 2013, to 376.8 MW at the end of the first quarter of 2020, a 25-fold growth rate in less than a decade. In July, a 60 MW-peak floating solar photovoltaic system on Tengeh Reservoir was launched – one of the world’s largest inland floating solar PV systems. “Innovation such as floating solar farms will help us overcome our physical constraints,” Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong said at the time.

While solar installations in Singapore continue to grow, its share of the overall electricity mix remains negligible at 3 per cent, despite strong policy support. Other renewables are non-existent. Singapore still lags behind countries with similar characteristics. Denmark, with a comparable population of 5.8 million, boasts 30 times more renewables at 9.7 GW - mostly provided by wind, with 1.3 GW of solar. Malaysia, whose GDP is roughly equivalent to Singapore at USD$340 billion, has 8.7 GW of renewables—mostly hydro, with 1.5 GW solar.

The direct import of renewable electricity is another feasible option to help Singapore reduce its gas dependency, according to the Singaporean government. Proposed changes to the Energy Bill could therefore be considered as a “proactive” measure in the long-term preparation for government-controlled electricity imports, thinks Owen.

“The government is a non-competitive company in the marketplace. They’re there essentially to ensure security of supply, and in this case, presumably to ensure that it gets greener,” Owen told Eco-Business.

“And the only way I can see them doing that is to come on as a major importer. if they’re going to have sizeable imports of renewables, then there’s got to be some consideration given to how the markets going to be restructured. Because existing companies are really not going to be terribly happy to see the market flooded with imports.”

Last October, the then-Minister for Trade and Industry Chan Chun Sing announced that Singapore will be importing 100 MW of electricity from Malaysia over the next two years. Singaporean solar firm Sunseap announced in July that it plans to build the world’s largest floating solar farm, at 2.2 GW, in Batam, Indonesia. The project will also incorporate 4 GW hours of energy storage, and export potential to Singapore via a 50-kilometre undersea transmission line.

A new Singapore-Austrialia Green Economy Agreement has been billed to lower carbon emissions and strengthen existing areas of co-operation, a joint statement said on Monday, including renewable energy and the adoption of low-carbon and green technologies.

Australian-Singapore venture, Sun Cable, said on 23 September that it will invest US$2.5 billion in Indonesia as part of an ambitious solar power project to provide the city-state with up to 15 per cent of its energy requirements by 2028. The Australia-Asia Power Link will from 2028 channel solar energy from the world’s largest solar farm and battery storage facility in Northern Australia, via a 5,000 km transmission system through Indonesian waters to Singapore. It will be the world’s longest subsea high-voltage cable. Sun Cable says that its energy provision will reduce emissions in the island nation by six million tonnes annually – enough to single-handedly fill the gap in Singapore’s 2030 emissions targets.

However, as the rush to build gas generators in the 2010s demonstrated, the price of electricity remains a factor in determining which technology will win out. For low-carbon imports to succeed, their final cost must be competitive with the alternatives. “There are a number of different potential projects in the pipeline that have been widely publicised – some more realistic than others,” a spokesperson from engineering firm Arup told Eco-Business. “In the end, it will come down to the levelised cost of energy from those imports.”

Singaporean electricity consumers will demand that renewables are cheaper than current alternatives, to the chagrin of generation companies who would prefer the reverse, said Owen.

“It’s going to damage the market structure, the design of the market, because at the moment everything has to pass through the marketplace. If there’s enormous amounts of power that can come in from overseas, I’m not sure that generation companies will be too keen to operate under the same bidding process, because that doesn’t give them the guarantees.”

“They’d have to come into some arrangement with the government. As soon as that happens, of course, the competitive design of the market has gone,” Owen adds. “So, it’s a very difficult situation.”

This article is part of a reporting series supported by Earth Journalism Network through its special collaborative journalism project “Available But Not Needed,” which brings together six media outlets and more than a dozen reporters across seven countries to explore how public and private investments continue to fund fossil fuel economies in Southeast Asia.