In the southern Polish city of Katowice last December, news coverage of the UN’s COP 24 meeting on climate change suddenly and dramatically surged, mostly thanks to a three-minute speech given by a Swedish teen activist with Asperger’s syndrome and the amplifying power of social media. “You say you love your children above all else,” declared 15-year-old Greta Thunberg to an audience of po-faced climate change negotiators: “And yet you are stealing their future in front of their very eyes.” She then accused them squarely of not doing or saying nearly enough to halt climate change — and of “not being mature enough to tell it like it is.” It was social media kryptonite. Her speech swiftly went viral.

Who out there is mature enough to avoid a Thunbergian scolding? Back in Katowice, the World Resources Institute (WRI) did its best to “tell it like it is.” Its researchers proudly brandished a 96-page “synthesis” of its World Resources Report: Creating A Sustainable Food Future. That synthesis looked impressive at first glance; it outlined how we could change global food systems, so they emit fewer greenhouse gases, occupy less land, and protect the earth’s biodiversity — all while producing ever higher volumes of food for a global population approaching ten billion by 2050.

Like most syntheses, though, there were holes; it all seemed a little light, trite and rushed. Perhaps this synthesis was birthed prematurely to accompany a roster of similar-minded sustainability reports released during COP24 — a high profile occasion that brings crucial global media and political oxygen to sustainability issues; it’s a chance for powerful research groups like the WRI to shine, and a pretty key moment to have fresh material to hand. Yet the material itself did feel fairly stale, taking 2010 as its benchmark year while looking forward to 2050. Such is the problem with compiling and crunching up to date, accurate global agricultural data. Such is also the problem with the format of lengthy report writing in a rapidly changing world.

Eight months later, a full and final version is out at last. Launched last week in Washington over a celebratory round of Impossible Burgers, the new edition is a heavyweight one, at least in a physical sense. Produced over the last decade or so in partnership with the World Bank, the UN Environment, UN Development Programme, and the French agricultural research agencies CIRAD and INRA, it is now a door-stopper of a volume at 564 pages. The list of contributors is about as distinguished and credible as those lists can be. But should it be swiftly devoured cover to cover, or used as an impressive yet unread shelf filler like your copy of Leo Tolstoy’s Anna Karenina?

In case it meets the fate of Karenina, AFN has carved out some of the insights. But first of all, does it pass the Thunberg test? Later in her Katowice speech, Thunberg said simply that “Until you start focusing on what needs to be done rather than what is politically possible, there is no hope.” Second Thunbergian axiom: “If solutions within the system are so impossible to find, maybe we should change the system itself.”

Wide-ranging, radical change

In this regard, the WRI report nicely avoids the hammer of Thunberg, anticipating, and addressing the need for wide-ranging and radical changes to our food systems. The report sets out to bridge three hauntingly wide “gaps.” Neither current politics or technology will be enough, the report’s writers say, estimating how present food production and distribution habits point to a yawning 56 percent “food gap” between what was produced in 2010 and food that will be needed in 2050. Current trends are sliding to a nearly 600 million-hectare “land gap,” between global agricultural land area in 2010, and expected agricultural expansion by 2050. That’s an area nearly twice the size of India. The third gap is a whopping 11-gigaton “greenhouse gas mitigation gap” between expected emissions from agriculture in 2050 and the level needed to meet the Paris Agreement and thereby keep global temperatures stable.

These predictions involve far wider gaps than others have previously estimated. How did they come to these numbers? Many of the report’s findings use the new GlobAgri-WRR model and WorldFish, which help quantify how to increase the availability of food, avoid deforestation, and reduce GHG emissions. Yet there is something odd here about the WRI settling on the UN’s population projection figure of 9.8 billion by 2050 as axiomatic. In fact, this is debatable. One report by Deutsche Bank sees the earth’s population peaking at 8.7 billion in 2055 — before shrinking to 8 billion by century’s end.

Still, UN evidence shows the number of hungry people in the world is growing, reaching 821 million in 2017 — one in every nine people — according to The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World 2018. And besides, it is better to gather momentum for solving the more challenging set of future scenarios rather than breed complacency. After all, as the English wit Dr Johnson once put it, “Depend upon it, sir, when a man knows he is to be hanged in a fortnight, it concentrates his mind wonderfully.”

A Five Course Menu To Save The Planet?

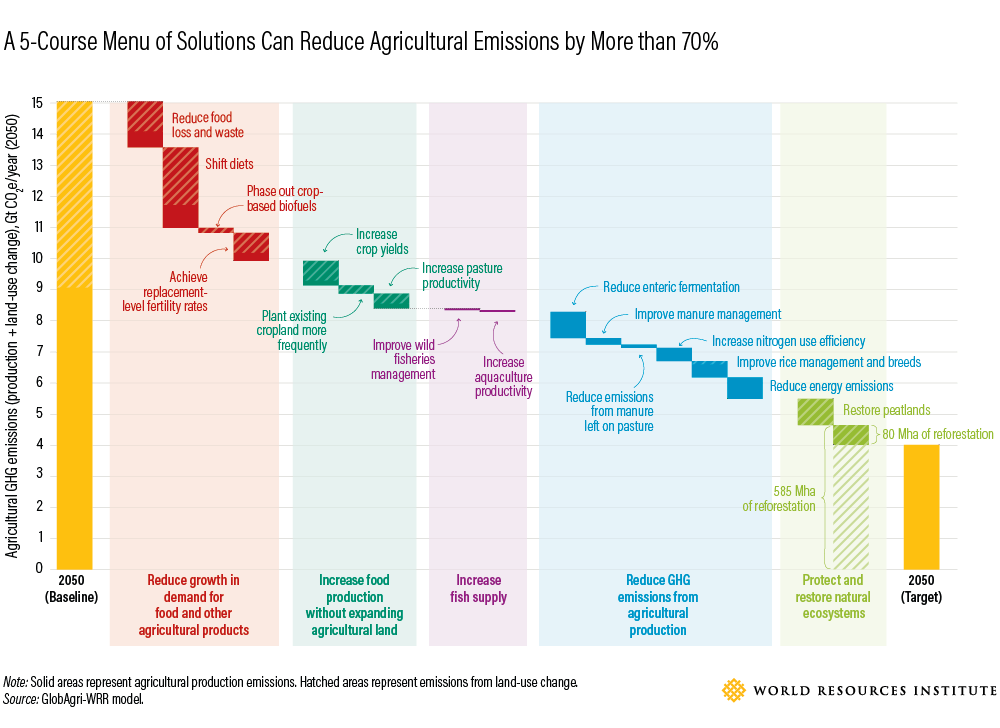

Commendably, the report is not content at that point to just ring alarm bells, as with Thunberg’s “Our house is on fire” speech at the World Economic Forum this January in Davos. Rather, the WRI lays out a menu of 22 solutions served over five courses:

- Reduce growth in demand (replace food loss and waste; shift diets; achieve replacement level fertility rates; phase out crop based biofuels)

- Increase food production without expanding agricultural land (increase crop yields; plant existing crop yields; increase pasture productivity)

- Increase fish supply (Improve wild fisheries management; increase aquaculture productivity.)

- Reduce greenhouse gas emissions from agricultural production (reduce enteric fermentation; improve manure management; reduce emissions from manure left on pasture; increase nitrogen use efficiency; improve rice management and breeds; reduce energy emissions)

- Protect and restore natural ecosystems. (Restore peatlands; 80 million hectares of reforestation.)

“Some items in the menu require more farmers to implement best practices that already exist today. Others need consumers to change behavior, or governments and businesses to reform policies,” write the report’s main authors Tim Searchinger, Craig Hanson, Richard Waite and Janet Ranganathan in an accompanying blog post. “The challenge is sufficiently large, however, that many solutions will require technological innovations. Advancing them is a major theme of our report.”

Can 10 technologies save the world?

In that post, they list 10 existing and emerging technologies to watch. To regular readers of AFN, these will not send you into paroxysms of amazement: plant-based meat-making; food preservation technologies; feeds to reduce a cow’s methane emissions; compounds to keep nitrogen in the soil; nitrogen-absorbing crops; rice that emits less methane; the gene-editing of crops; higher yield palm oil; algae-based fish feeds; solar-powered fertilizers.

Quite a few agri- and food tech companies get a shout-out here, and plant-based meat groups Impossible Foods and Beyond Meat both get a fair few positive mentions throughout the report. (The WRI has done a lot of consulting work on shifting consumer diets onto these plant-based alternatives; you can follow this work via their initiatives the Better Buying Lab, or sign up to their Cool Food Pledge.)

In the food waste space, the report writers largely applaud the spray-on food preservation films at Apeel Sciences, or the decomposition delaying abilities at Nanology and Bluapple. The report also cites the UK as an example of a country that has succeeded in reducing its food waste, but it fails to mention some of the latest technologies and strategies emerging there and some of its continuing struggles to tackle that problem — again, a slight sense of the world moving on before this report got out the stable. On the task of boosting palm oil yields, the company PT Smart is held up as an exemplar, having bred a variety with triple the current average yield of Indonesia’s oil palm trees. Meanwhile, for reducing the amount of cow burps, the report praises the Dutch company DSM for “its product called 3-NOP that reduces these methane emissions by 30% in tests, and does not appear to have health or environmental side effects.”

Livestock genomics and regen ag left in the dirt

Perhaps feeling slightly left out of this report will be champions of genomics for livestock to boost their yields or resistance to disease; the world’s seaweed producers might also feel they did not get enough of a mention. The same goes for regenerative agriculture. The report devotes an entire chapter to it, but its conclusions lean toward skepticism; it clashes with other conclusions emerging in the space promising impressive levels of carbon sequestration, such as White Oak Pastures that recently revealed results of a life cycle assessment of its practices showing it stored “more carbon in the soil than their cows emit during their lives.” (The same group behind Impossible’s own LCA conducted the report.)

“We do not believe that carbon sequestration in soils should receive much effort for climate mitigation purposes alone,” the WRI writers say, suggesting some of the benefits promised in some particular studies are “over-optimistic.”

The report’s lack of enthusiasm for regenerative agriculture angered proponents of a similar term — agroecology.

“I don’t think the report truly represents the transformative change that the global food system needs to undergo,” Hans Herren, president of the Washington-based Millennium Institute and a winner of the World Food Prize, told the National Geographic, outlining a different methodology, where the UN Food and Agriculture Organization and UN Committee on World Food Security (CFS), among others, endorse a so-called agroecological approach to food production. This term passes unmentioned, Herren complained. The National Geographic describes agroecology as mimicking nature and “replacing external inputs like chemical fertilizer with knowledge of how a combination of plants, trees, and animals can enhance the productivity of land.” The CFS, Herren’s institute, has by the way recently published its own report into how to feed the world sustainably.

Who’s this report for and is it already out of date?

While I read through an advance copy of the WRI report for reviewing purposes, I was tucked inside a sweltering London cafe on Fleet Street, as good a place as any for journalism, and a stone’s throw from the Extinction Rebellion crowds bathing in the sunlight. Out there, protesters talked animatedly about how humanity is potentially doomed, parking a light pink sculpture of a giant dodo and a bright blue sailboat outside London’s Royal Courts of Justice. This report will not bring these climate issues alive in such a way, I thought, somewhat obviously. But also, will it be useful as its contents start to age?

That question seemed above my pay grade, so I asked Tomer Shalit, CEO of the Swedish software company ClimateView. His startup has just created Panorama, an open-source software to map out Sweden’s path to a carbon-neutral future. His feelings about the report were mixed, and since the first words of this report went to a Swede, the last shall go that way for the sake of symmetry:

“The report is very accessible and a fantastic starting point as it clearly defines the issues that exist along with the possible solutions to these and their respective impact. It also breaks down the solutions into clear hierarchies and dependencies explaining how each can have both positive and negative effects on one another,” says Shalit.

“What the report does not do, however, is go further in suggesting the specific localised policy and projects required in order to kickstart the proposed solutions. It would be very hard for the report to do so in its current form since, as it states, the actions themselves will be very different from nation to nation and economy to economy. Actions to be taken in Holland are obviously completely different from ones necessary in Kenya, for example.”

Is the dream scenario a “ClimateView-type” blueprint of the report that’s publicly available, tailorable to specific regions, and can update in real-time how projections match the reality? Of course, Shalit thinks so.

“This way, those who are tasked with executing the conclusions of this report would have a clear starting point from which to break down the ambitious long term goals of the report, into short term actionable steps,” he adds. “As different states, regions and cities start working on their respective roadmaps, they will also have the opportunity to learn from others, based on the same blueprint, comparing data and actions.”

As a tech journalist aware of the potential for rapid change and transformation in this and any other industry, it seems crazy to me to be using nearly 10-year old data as a guide for decision making today and in the future. Particularly when we already have the tools to build something more dynamic.

As Shalit finished: “We manage what we measure, so therefore what gets measured gets managed.”

Image: Rome, Italy – 04 March, 2019: A girl on a ladder begins a mural at Trullo, a suburb of Rome, depicting Greta Thunberg – from iStock

Sponsored

International Fresh Produce Association launches year 3 of its produce accelerator